Lev Tolstoy received a phonograph from Thomas Edison in 1908.

He then proceeded to make some recordings, as follows:

He then proceeded to make some recordings, as follows:

THOUGHTS FOR 2015

When the Spiritual and Physical Essences Combine

Striking a Balance for the New Year

Aristotle spoke of 'the doctrine of the mean'; striking a balance without excess in order to live a harmonious, balanced existence. I refer to this as the spiritual - physical essence interaction.

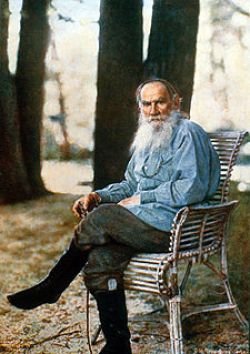

Despite the fact that he was a wealthy man with a retinue of servants, Leo Tolstoy did manual labour every day; gardening, plowing and tending the huge orchard at his beloved Yasnaya Polyana. Being an accomplished horseman he continued riding well into his 80th year. He once said that without the estate he could not live.

But he did not mean the luxury, the servants, the many buildings and rooms - he meant the soil, trees, flowers, fruit, his tending, his watching them grow, his physical organic contact with the soil.

In fact, Lev Tolstoy believed that no matter how advanced intellectually or spiritually a person may be, he could not fulfill his full mandate on earth if he was not in contact with nature.

Nature was the full evidence of the Living Spirit within all things; and without this knowledge and contact with nature, man could not live a complete and whole life.

The Doukhobor credo was: Toil and Peaceful Life. What did this mean?

It meant that, once more, just as in the case of Tolstoy, man must be in peaceful contact, not only with his brethren, but with all living things. In order for the spiritual life to attain its potential, one must be in harmony and peace with nature first, as all that followed was part of the whole.

This concept was also well illustrated by the indigenous natives of North America; the land was not something that one owned, but something that one borrowed from his grandchildren. Consequently, recent agitation over land claims is to insure the protection of the land in its natural state, not over the ownership of mineral resources, as some interpret it to be.

Peter Verigin, the inspired leader whose influence spanned two continents, took this a step further - if we bow to each other, recognizing the spirit of God within all living brethren, then our bodies, this physical living space, this temple of the Holy Presence, must be clean also - undefiled by noxious stimulants such as alcohol and tobacco, and meat, thus respecting all other living things as our brethren who also are endowed with the Transcendental Spirit, as it is present in all living things.

Thus the Doukhobors, very early in their history, realized that man must live in harmony with nature in order to fulfill his full potential and ensure a balanced ecology for future generations.

Stripped of the motivations of profit and greed there was plenty for everyone, one's self and one's family and the community. Excess could be given to those who had not, those in need. Thus the spiritual essence gave rise to the practical application of the physical essence, and everyone benefited. The poet Thomas Browne said: "All things are artificial, for nature is the art of God."

How well that fits in with the Doukhobor concept! When the Doukhobors rejected the artificial trappings and ceremonies of the Orthodox Church, they were returning to a more natural state - a state where man could worship and be in contact with God in a natural state, not in a gilded, festooned, ornate Church, decorated with gold and silver. Christ is reputed to have said: "Wherefore one or more is gathered in my name, there will I be also." Certainly that meant that the Doukhobors could worship under the open sky or in any friend's house, and God would be there - just as He was present in all living things.

Our generation is now reaping the results of ignoring such simple advice. Subjected to greed and avarice, our present mankind has ruthlessly exploited nature so we can hardly survive on earth anymore. The Great Lakes have been poisoned to such a degree that the entire ecosystem of one quarter of Canada is in peril; there is nowhere in North America that one can drink untreated water safely; DDT contamination is found in the liver of bears and penguins at the North and South Poles.

This is the legacy of the physical essence overtaking, and not being guided by the spiritual essence. Fueled by a capitalistic orgy of consumerism, we are steadily losing track of the essentials.

The need for regaining this balance has never been greater than it is today. We failed our younger generation because we have contributed to the current state of the world. A modern quote says: 'If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem.'

What a devastating legacy of ruin we have presented to future generations - all because we lost the balance between the spiritual and the physical essence.

Let’s resolve to form a New Year’s resolution to address this impending disaster in what ever, even minuscule way, we can. We can continue to live for a while, in a polluted industrial park or we can help preserve a fragile eco-system. Changing the world begins with changing oneself. Let's look forward to a new year with energy and optimism, and determination that the size of our foot print can make a difference!

Despite the fact that he was a wealthy man with a retinue of servants, Leo Tolstoy did manual labour every day; gardening, plowing and tending the huge orchard at his beloved Yasnaya Polyana. Being an accomplished horseman he continued riding well into his 80th year. He once said that without the estate he could not live.

But he did not mean the luxury, the servants, the many buildings and rooms - he meant the soil, trees, flowers, fruit, his tending, his watching them grow, his physical organic contact with the soil.

In fact, Lev Tolstoy believed that no matter how advanced intellectually or spiritually a person may be, he could not fulfill his full mandate on earth if he was not in contact with nature.

Nature was the full evidence of the Living Spirit within all things; and without this knowledge and contact with nature, man could not live a complete and whole life.

The Doukhobor credo was: Toil and Peaceful Life. What did this mean?

It meant that, once more, just as in the case of Tolstoy, man must be in peaceful contact, not only with his brethren, but with all living things. In order for the spiritual life to attain its potential, one must be in harmony and peace with nature first, as all that followed was part of the whole.

This concept was also well illustrated by the indigenous natives of North America; the land was not something that one owned, but something that one borrowed from his grandchildren. Consequently, recent agitation over land claims is to insure the protection of the land in its natural state, not over the ownership of mineral resources, as some interpret it to be.

Peter Verigin, the inspired leader whose influence spanned two continents, took this a step further - if we bow to each other, recognizing the spirit of God within all living brethren, then our bodies, this physical living space, this temple of the Holy Presence, must be clean also - undefiled by noxious stimulants such as alcohol and tobacco, and meat, thus respecting all other living things as our brethren who also are endowed with the Transcendental Spirit, as it is present in all living things.

Thus the Doukhobors, very early in their history, realized that man must live in harmony with nature in order to fulfill his full potential and ensure a balanced ecology for future generations.

Stripped of the motivations of profit and greed there was plenty for everyone, one's self and one's family and the community. Excess could be given to those who had not, those in need. Thus the spiritual essence gave rise to the practical application of the physical essence, and everyone benefited. The poet Thomas Browne said: "All things are artificial, for nature is the art of God."

How well that fits in with the Doukhobor concept! When the Doukhobors rejected the artificial trappings and ceremonies of the Orthodox Church, they were returning to a more natural state - a state where man could worship and be in contact with God in a natural state, not in a gilded, festooned, ornate Church, decorated with gold and silver. Christ is reputed to have said: "Wherefore one or more is gathered in my name, there will I be also." Certainly that meant that the Doukhobors could worship under the open sky or in any friend's house, and God would be there - just as He was present in all living things.

Our generation is now reaping the results of ignoring such simple advice. Subjected to greed and avarice, our present mankind has ruthlessly exploited nature so we can hardly survive on earth anymore. The Great Lakes have been poisoned to such a degree that the entire ecosystem of one quarter of Canada is in peril; there is nowhere in North America that one can drink untreated water safely; DDT contamination is found in the liver of bears and penguins at the North and South Poles.

This is the legacy of the physical essence overtaking, and not being guided by the spiritual essence. Fueled by a capitalistic orgy of consumerism, we are steadily losing track of the essentials.

The need for regaining this balance has never been greater than it is today. We failed our younger generation because we have contributed to the current state of the world. A modern quote says: 'If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem.'

What a devastating legacy of ruin we have presented to future generations - all because we lost the balance between the spiritual and the physical essence.

Let’s resolve to form a New Year’s resolution to address this impending disaster in what ever, even minuscule way, we can. We can continue to live for a while, in a polluted industrial park or we can help preserve a fragile eco-system. Changing the world begins with changing oneself. Let's look forward to a new year with energy and optimism, and determination that the size of our foot print can make a difference!

VERIGIN - TOLSTOY - 1895- 1909

Peter Verigin [1895]: There is a superiority of live communication over dead books. If we preserved what was already given to us from above, we should be perfectly happy. Whatever is necessary and lawful must inevitably be in each one of us and comes directly from above or from within ourselves.

L. N. Tolstoy[1895]:

I write books and therefore I know all the harm that they cause; how they have re-interpreted the Gospel. Now we cannot let just the enemy have this powerful tool to use for deceit. The big challenge is in throwing out the lie without throwing out some of the truth with it. I embrace you as a brother.-

Peter replies [1895]:

Christ's saying 'What ye hear in the ear, that preach ye upon the housetops', It must be taken in its literal sense: preach. It is not your writings that appeal to me, but rather your life, your actions, the way you left an artificial life for a natural human one. In the Caucasus the government knows that we refuse military service, and not to kill human beings. They've begun imprisoning the women too. The question of 'non-violent resistance to evil' is completely answered to my mind. You, dear brother Lev Nicolievich, have personally done a great deal for our age.

Leo: People must realize that no matter how useful and important book printing, railways, ploughs or scythes seem to be, we do not really need them and they can just as well disappear until we learn how to make them without destroying people's lives and happiness. Turning back the clock is neither desirable nor possible. I was glad to read how you manage to eke out a living for yourself. I have become rather poor at doing this, surrounded as I am by all sorts of luxuries which I hate but have not the strength to extricate myself from. I keep on trying. Your loving friend, Leo Tolstoy.

Peter: I am disturbed by the frightfully arbitrary treatment of Christians in the Caucasus. The authorities are dispersing them among the local population. And they are not allowing wives and children to go with their husbands. The most dangerous element in the Christian movement, from the point of view of the established order is the refusal to kill a human being.

L. N. Tolstoy [1898]:

Dear Brother Peter Vasilevich.

Your parents are alive and well. Nothing has been decided yet about where to emigrate. There have been some good proposals from America. I ask you not to lose heart and remember not only that many, many brothers are thinking about you and love you, but also that God is thinking about us and loves us in the measure that we do His will and help bring about His kingdom in our hearts and in the world. Your loving brother, Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin [1898]:

Esteemed Lev Nicolievich! The lack of development of the spirit in the life of a people is unquestionably the root cause of all a people's ills, but the lowering or raising of a people's spirits largely depends on the material conditions. Give people room to breathe freely, and then the people will strengthen themselves and develop and advance under the influence of the universal evolution of life! I am almost positively against emigration. The members of our community are in need of self-improvement, and so wherever we went we would take our weaknesses with us.

L. N. Tolstoy [1898]: Dear Brother Peter Vasilevich.

The ship that is to carry the first migrants is to arrive for them on the 4th of December. I was especially happy to read your ideas on the re-settlement. I share your opinion completely - namely that it is not the place where we live that is important but our inner mental sate. Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free. Your letter to the Minister of Internal Affairs is unlikely to produce any action. But I am almost certain that once all the migrants are settled in Canada, they will release you. Life is in the spirit rather than the flesh.

Verigin [1899]: My esteemed Lev Nikolaevich

I have great hopes once our emigrating brethren are safely across the ocean and settled in their places, they should be able to begin a good life there. First and foremost there must be full freedom of thought for every individual. In communal living people can be united only by their vital material interests. I think some agriculture could be arranged quite properly. Teaching literacy to the children must be considered a priority, the ability to read and write, just like the mending of clothes and shoes, the knitting of stockings, the binding of harrow chains, etc. Only you have to watch out that the child doesn't become a 'professional' cobbler, or a girl become a hosiery-maker, like many people who become 'professors of literacy' but remain perfect ignoramuses in other departments of life.

L. N. Tolstoy [1901]: Dear Brother Peter Vasilevich,

If the Doukhobors harbour a personal superstition, ascribing a supernatural significance to your personality it should not be encouraged. I believe that in a Christian society all are equal and that everybody learns from each other: the old from the young, the educated from the uneducated, the clever from the dull-minded, and even the virtuous from the reprobate. Everybody learns from each other. I have not ceased trying to persuade the government to let you and the other exiles leave. I made another attempt just the other day, with a letter on this subject to the Tsar. I shall try again. Farewell. My best brotherly wishes to you. Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin 1902: Dear Friend Lev Nicolievich!,

I have been staying with the dear Chertkov family. On the 20th I plan to leave for America, I should have gone straight to see my elderly mother. I was at a meeting in London. Vladimir Gregorovich read a well written account he had prepared about the Doukhobors. The audience listened attentively, and later I was asked to explain the Doukhobor views on several issues.

L. N. Tolstoy [1902]: Dear Brother Petr Vasilevich,

I shall tell you only briefly that, according to the latest reports, their material needs are being well supplied, I only hope they are also prospering spiritually. And I believe they will, in spite of the fact that outwardly many of them seem to have somehow been weakened at present. Your Brother, Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin [1903]:

Vladimir Grigor'evich Chertkov greeted me with outstretched arms. He went with me to Liverpool and saw me aboard ship. The crossing was quite stormy. Three Doukhobors came to meet me in Saint John along with someone sent by the Minister from Ottawa, Just three days later I was with the Doukhobors. You can imagine, my dear Lev Nicolievich, how my soul was overflowing with ecstasy and feelings of joy upon arriving at the first Doukhobor village The second village was the one where my mother is living; I found her extremely cheerful and quite healthy for her years.

Tolstoy [1903]:

Thank you for writing me. Farewell, and may God grant you and all the Doukhobor brethren the highest possible good in the world - unity and love among yourselves.

Lovingly, Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin [1904]:

My dear Lev Nicolievich, I am happy to inform you that we are all alive and well, especially in the Spirit, thank God. The winter here has been a long one. Now, spring is opening up. All the children in the Doukhobor villages are singing their greeting to spring: 'prishla Vesna k nam molodaya" [Spring has come to us young and fair]! And really, she is eternally young! How marvelously the world is constructed! How fervently I wish, dear Lev Nicolievich, that you could be here in the Doukhobor villages and see these 8- to 10-year old children singing their songs of spring. I feel such images - these groups of children - would prove a significant reward for your long labours as a fighter for truth.

Tolstoy:[1905]:

I received your kind and interesting letter some time ago now and was so glad both that you remember me and that the financial affairs of your community are coming along well. God grant only that material success does not mean a weakening of spiritual effort and striving for perfection. I hope, and I wish that this is how it will be with the Doukhobors. My brotherly greetings to you and all those who know me.

P. V. Verigin [1905]: Dear Friend Lev Nicolievich,

Your fears for the Doukhobors' future in Canada are valid and understandable. But I cannot refuse to accept people's close participation in building material progress since in many respects the spiritual does not depend upon us, it is something that touches each one individually. Christ says: the world knoweth me not, but you know me. Of course, this 'knowledge' should be interpreted as unity of the spirit.

L. N. Tolstoy [1909]:

I thank you, kind brother Peter, for your letter and joyful news of your brethren, especially about the striving for spiritual perfection you wrote about. Whatever good there is in our life is found in the soul, in its drawing nearer to God. Concern over physical things for the most part only detracts from the inner workings of the soul. Give my love to the brethren, along with my regret that I am physically separated from them and from you.

Lovingly, Leo Tolstoy.

Peter Verigin [1895]: There is a superiority of live communication over dead books. If we preserved what was already given to us from above, we should be perfectly happy. Whatever is necessary and lawful must inevitably be in each one of us and comes directly from above or from within ourselves.

L. N. Tolstoy[1895]:

I write books and therefore I know all the harm that they cause; how they have re-interpreted the Gospel. Now we cannot let just the enemy have this powerful tool to use for deceit. The big challenge is in throwing out the lie without throwing out some of the truth with it. I embrace you as a brother.-

Peter replies [1895]:

Christ's saying 'What ye hear in the ear, that preach ye upon the housetops', It must be taken in its literal sense: preach. It is not your writings that appeal to me, but rather your life, your actions, the way you left an artificial life for a natural human one. In the Caucasus the government knows that we refuse military service, and not to kill human beings. They've begun imprisoning the women too. The question of 'non-violent resistance to evil' is completely answered to my mind. You, dear brother Lev Nicolievich, have personally done a great deal for our age.

Leo: People must realize that no matter how useful and important book printing, railways, ploughs or scythes seem to be, we do not really need them and they can just as well disappear until we learn how to make them without destroying people's lives and happiness. Turning back the clock is neither desirable nor possible. I was glad to read how you manage to eke out a living for yourself. I have become rather poor at doing this, surrounded as I am by all sorts of luxuries which I hate but have not the strength to extricate myself from. I keep on trying. Your loving friend, Leo Tolstoy.

Peter: I am disturbed by the frightfully arbitrary treatment of Christians in the Caucasus. The authorities are dispersing them among the local population. And they are not allowing wives and children to go with their husbands. The most dangerous element in the Christian movement, from the point of view of the established order is the refusal to kill a human being.

L. N. Tolstoy [1898]:

Dear Brother Peter Vasilevich.

Your parents are alive and well. Nothing has been decided yet about where to emigrate. There have been some good proposals from America. I ask you not to lose heart and remember not only that many, many brothers are thinking about you and love you, but also that God is thinking about us and loves us in the measure that we do His will and help bring about His kingdom in our hearts and in the world. Your loving brother, Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin [1898]:

Esteemed Lev Nicolievich! The lack of development of the spirit in the life of a people is unquestionably the root cause of all a people's ills, but the lowering or raising of a people's spirits largely depends on the material conditions. Give people room to breathe freely, and then the people will strengthen themselves and develop and advance under the influence of the universal evolution of life! I am almost positively against emigration. The members of our community are in need of self-improvement, and so wherever we went we would take our weaknesses with us.

L. N. Tolstoy [1898]: Dear Brother Peter Vasilevich.

The ship that is to carry the first migrants is to arrive for them on the 4th of December. I was especially happy to read your ideas on the re-settlement. I share your opinion completely - namely that it is not the place where we live that is important but our inner mental sate. Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free. Your letter to the Minister of Internal Affairs is unlikely to produce any action. But I am almost certain that once all the migrants are settled in Canada, they will release you. Life is in the spirit rather than the flesh.

Verigin [1899]: My esteemed Lev Nikolaevich

I have great hopes once our emigrating brethren are safely across the ocean and settled in their places, they should be able to begin a good life there. First and foremost there must be full freedom of thought for every individual. In communal living people can be united only by their vital material interests. I think some agriculture could be arranged quite properly. Teaching literacy to the children must be considered a priority, the ability to read and write, just like the mending of clothes and shoes, the knitting of stockings, the binding of harrow chains, etc. Only you have to watch out that the child doesn't become a 'professional' cobbler, or a girl become a hosiery-maker, like many people who become 'professors of literacy' but remain perfect ignoramuses in other departments of life.

L. N. Tolstoy [1901]: Dear Brother Peter Vasilevich,

If the Doukhobors harbour a personal superstition, ascribing a supernatural significance to your personality it should not be encouraged. I believe that in a Christian society all are equal and that everybody learns from each other: the old from the young, the educated from the uneducated, the clever from the dull-minded, and even the virtuous from the reprobate. Everybody learns from each other. I have not ceased trying to persuade the government to let you and the other exiles leave. I made another attempt just the other day, with a letter on this subject to the Tsar. I shall try again. Farewell. My best brotherly wishes to you. Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin 1902: Dear Friend Lev Nicolievich!,

I have been staying with the dear Chertkov family. On the 20th I plan to leave for America, I should have gone straight to see my elderly mother. I was at a meeting in London. Vladimir Gregorovich read a well written account he had prepared about the Doukhobors. The audience listened attentively, and later I was asked to explain the Doukhobor views on several issues.

L. N. Tolstoy [1902]: Dear Brother Petr Vasilevich,

I shall tell you only briefly that, according to the latest reports, their material needs are being well supplied, I only hope they are also prospering spiritually. And I believe they will, in spite of the fact that outwardly many of them seem to have somehow been weakened at present. Your Brother, Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin [1903]:

Vladimir Grigor'evich Chertkov greeted me with outstretched arms. He went with me to Liverpool and saw me aboard ship. The crossing was quite stormy. Three Doukhobors came to meet me in Saint John along with someone sent by the Minister from Ottawa, Just three days later I was with the Doukhobors. You can imagine, my dear Lev Nicolievich, how my soul was overflowing with ecstasy and feelings of joy upon arriving at the first Doukhobor village The second village was the one where my mother is living; I found her extremely cheerful and quite healthy for her years.

Tolstoy [1903]:

Thank you for writing me. Farewell, and may God grant you and all the Doukhobor brethren the highest possible good in the world - unity and love among yourselves.

Lovingly, Leo Tolstoy.

P. V. Verigin [1904]:

My dear Lev Nicolievich, I am happy to inform you that we are all alive and well, especially in the Spirit, thank God. The winter here has been a long one. Now, spring is opening up. All the children in the Doukhobor villages are singing their greeting to spring: 'prishla Vesna k nam molodaya" [Spring has come to us young and fair]! And really, she is eternally young! How marvelously the world is constructed! How fervently I wish, dear Lev Nicolievich, that you could be here in the Doukhobor villages and see these 8- to 10-year old children singing their songs of spring. I feel such images - these groups of children - would prove a significant reward for your long labours as a fighter for truth.

Tolstoy:[1905]:

I received your kind and interesting letter some time ago now and was so glad both that you remember me and that the financial affairs of your community are coming along well. God grant only that material success does not mean a weakening of spiritual effort and striving for perfection. I hope, and I wish that this is how it will be with the Doukhobors. My brotherly greetings to you and all those who know me.

P. V. Verigin [1905]: Dear Friend Lev Nicolievich,

Your fears for the Doukhobors' future in Canada are valid and understandable. But I cannot refuse to accept people's close participation in building material progress since in many respects the spiritual does not depend upon us, it is something that touches each one individually. Christ says: the world knoweth me not, but you know me. Of course, this 'knowledge' should be interpreted as unity of the spirit.

L. N. Tolstoy [1909]:

I thank you, kind brother Peter, for your letter and joyful news of your brethren, especially about the striving for spiritual perfection you wrote about. Whatever good there is in our life is found in the soul, in its drawing nearer to God. Concern over physical things for the most part only detracts from the inner workings of the soul. Give my love to the brethren, along with my regret that I am physically separated from them and from you.

Lovingly, Leo Tolstoy.

Lev Tolstoy and the Doukhobors

By Larry Ewashen, Curator, Doukhobor Discovery Centre, Castlegar, BC.

Presented Sept. 22, 2010 at the Tolstoy Forum,

University of the Fraser Valley, Abbottsford, BC.

By Larry Ewashen, Curator, Doukhobor Discovery Centre, Castlegar, BC.

Presented Sept. 22, 2010 at the Tolstoy Forum,

University of the Fraser Valley, Abbottsford, BC.

THE ADDRESS:

Leo Tolstoy’s activities were far ranging and diverse, and one the least known activities that had perhaps the most direct impact on a single group, was his assistance to the Doukhobors, who migrated to Canada in 1899.

As a sign of rejection of violence and killing, and their adherence to Christ’s commandment, ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ the Doukhobors burned all of their weapons in 1895. Peter Verigin’s direct request was:

‘It would be appropriate for the Doukhobors to reject the military service completely. All weapons belonging to the Doukhobors, for example, rifles, revolvers, sabers, swords, which they had acquired distancing themselves from the teachings of Christ, must be gathered in one place and as a symbol of non-violence and in fulfillment of the commandment not to kill, bring all to fire remembering the words of Christ that those who take up the sword will perish by the sword.’

After this arms’ burning took place in three separate areas of Russia in 1895, the Doukhobors were severely persecuted and banished to Siberia. Alarmed by reports of this severe repression, Tolstoy sent Pavel Burikov to investigate. This resulted in a publication, Christian Martyrdom in Russia: Persecution of the Spirit-Wrestlers (or Doukhobortsi) in the Caucasus, and some smaller pamphlets sympathetic to the Doukhobors, and world wide publicity aimed at the Russian government to allow the Doukhobors to emigrate. Tolstoy and his publisher Vladimir Chertkov, took up the Doukhobor cause in earnest. Devoting the royalties from a hastily completed novel, Resurrection and fund raising among his wealthy friends, Tolstoy raised 30,000 roubles, about half of the total emigration costs. To this day he is revered among Doukhobors as their saviour in dire time of persecution. In 1897, amidst speculation that Leo Tolstoy would be nominated for the first Nobel prize for peace, Tolstoy wrote to the newspaper in Stockholm, declining such nomination and suggesting that the Doukhobors be nominated instead.

He began his letter by saying:

‘I would say that the terms of Nobel’s will concerning individuals who have done the most to serve the cause of peace are extremely difficult to fulfill. People who really serve the cause of peace do so because they serve God, and so they do not need monetary rewards and will not accept them. But I would say that the terms of the will would be amply fulfilled if the prize money were to go to the needy families of those who serve the cause of peace. I am talking about the Caucasus Doukhobors. No one in our time has served or is continuing to serve the cause of peace more effectively and earnestly than these people’.

He goes on to describe the Doukhobors, their plight and their needs. Here we see a foundation for future appeals for the migration, as he is realizing their needs, and eventual necessity for leaving Russia.

He then goes on to use this as a platform for his own views:

‘So, if peace has not yet come, it is not because there is no general desire among people for it, but only because of an insidious deception by which people have believed and maintain that peace is impossible and war unavoidable’.

In the end he sums up: ‘ . . . nobody more than they deserves to receive the money which Nobel bequeathed serving the cause of peace’.

He admired them as living an ideal life close to his own beliefs and having the courage to implement two basic Christian beliefs, Resist not evil with evil, and Thou shalt not kill.

As a postscript, the letter was published, his advice was not heeded, his name remained on the short list for both the Peace and Literature prize. He was passed over for both.

The greatest source of the philosophical and religious tenets of the Doukhobors in relation to Tolstoy’s beliefs, can be found in the collected correspondence between Tolstoy and Peter Verigin from 1895 to 1910. This correspondence has resulted in a book in Russian and English, and contains a selection of their letters from 1895 to 1910.

Leo Tolstoy’s activities were far ranging and diverse, and one the least known activities that had perhaps the most direct impact on a single group, was his assistance to the Doukhobors, who migrated to Canada in 1899.

As a sign of rejection of violence and killing, and their adherence to Christ’s commandment, ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ the Doukhobors burned all of their weapons in 1895. Peter Verigin’s direct request was:

‘It would be appropriate for the Doukhobors to reject the military service completely. All weapons belonging to the Doukhobors, for example, rifles, revolvers, sabers, swords, which they had acquired distancing themselves from the teachings of Christ, must be gathered in one place and as a symbol of non-violence and in fulfillment of the commandment not to kill, bring all to fire remembering the words of Christ that those who take up the sword will perish by the sword.’

After this arms’ burning took place in three separate areas of Russia in 1895, the Doukhobors were severely persecuted and banished to Siberia. Alarmed by reports of this severe repression, Tolstoy sent Pavel Burikov to investigate. This resulted in a publication, Christian Martyrdom in Russia: Persecution of the Spirit-Wrestlers (or Doukhobortsi) in the Caucasus, and some smaller pamphlets sympathetic to the Doukhobors, and world wide publicity aimed at the Russian government to allow the Doukhobors to emigrate. Tolstoy and his publisher Vladimir Chertkov, took up the Doukhobor cause in earnest. Devoting the royalties from a hastily completed novel, Resurrection and fund raising among his wealthy friends, Tolstoy raised 30,000 roubles, about half of the total emigration costs. To this day he is revered among Doukhobors as their saviour in dire time of persecution. In 1897, amidst speculation that Leo Tolstoy would be nominated for the first Nobel prize for peace, Tolstoy wrote to the newspaper in Stockholm, declining such nomination and suggesting that the Doukhobors be nominated instead.

He began his letter by saying:

‘I would say that the terms of Nobel’s will concerning individuals who have done the most to serve the cause of peace are extremely difficult to fulfill. People who really serve the cause of peace do so because they serve God, and so they do not need monetary rewards and will not accept them. But I would say that the terms of the will would be amply fulfilled if the prize money were to go to the needy families of those who serve the cause of peace. I am talking about the Caucasus Doukhobors. No one in our time has served or is continuing to serve the cause of peace more effectively and earnestly than these people’.

He goes on to describe the Doukhobors, their plight and their needs. Here we see a foundation for future appeals for the migration, as he is realizing their needs, and eventual necessity for leaving Russia.

He then goes on to use this as a platform for his own views:

‘So, if peace has not yet come, it is not because there is no general desire among people for it, but only because of an insidious deception by which people have believed and maintain that peace is impossible and war unavoidable’.

In the end he sums up: ‘ . . . nobody more than they deserves to receive the money which Nobel bequeathed serving the cause of peace’.

He admired them as living an ideal life close to his own beliefs and having the courage to implement two basic Christian beliefs, Resist not evil with evil, and Thou shalt not kill.

As a postscript, the letter was published, his advice was not heeded, his name remained on the short list for both the Peace and Literature prize. He was passed over for both.

The greatest source of the philosophical and religious tenets of the Doukhobors in relation to Tolstoy’s beliefs, can be found in the collected correspondence between Tolstoy and Peter Verigin from 1895 to 1910. This correspondence has resulted in a book in Russian and English, and contains a selection of their letters from 1895 to 1910.

The letters . . .

Andrew Donskov, editor of Leo Tolstoy and Peter Verigin: Correspondence, talks of the written dialogue between Tolstoy and Verigin as one between equals: They loved and respected each other, in fact, Verigin experienced some sort of filial feeling, a father-son feeling towards the older Tolstoy, which he expressed very tenderly at times. Tolstoy was 67 and Verigin 36 when the correspondence began. When they met face to face, Tolstoy was fully conscious of Verigin’s outstanding intellect. “Confess God in spirit and soul” was the chief commandment of the Doukhobors, as they called themselves, or members of the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, as Verigin proposed to call them. Uniting all people in goodness and love, living by the laws of conscience rather than by the decrees of government and church authorities — these ideas are found again and again in Verigin’s letters, each time being met by sympathetic response from Tolstoy.

Verigin’s main thesis was: “To believe in God means believing in life”. Believing in life on earth, and thereby to strive for life eternal. Spirituality is not necessarily synonymous with suffering, or renouncing all earthly blessings. One must live, love, labour, be happy, and resolutely endure suffering — as adversity, but not as the only sure way to God.

Tolstoy wrote beautifully on this subject in his diary of 1894:

‘No, this world is not a joke, nor merely a valley of temptation one must pass through on the way to a better, eternal world. Rather, it is one of the eternal worlds which is marvellous and joyous and which we not only can but must make even more marvellous and joyous for those around us as well as for those who will continue to live in it after we are gone’.

We can see here their parallel beliefs.

They both believed in the fundamental concept that life on earth was real and in the present, and not as some Christian teachings, a mortal existence as a trial for some future reward in heaven.

In a lecture at the University of Victoria, Dr. Galina Alexeeva, Head of Academic Research at Yasnaya Polyana, State Museum of Leo Tolstoy, noted the highlights of Leo Tolstoy’s life and the highlights in development of the history of the Doukhobors, which began with an early meeting in 1894 in Moscow between Tolstoy and Vasili Verigin, my great grandfather, as Peter was being transported to Siberia, and which culminated in the emigration of the Doukhobors in 1899 with the aid of Leo Tolstoy and his literary legacy.

Although the Doukhobors were basically free hold peasant farmers, some of them belonging to estates, as was the case with our Ewashen family in Tambov, who were only allowed to join their brethren in exile after repeated requests, it is interesting to note that their plight and eventual deliverance emanated from the highest intellectual and bourgeois circles of the day, an international set at that.

Prince Peter Kropotkin, famous anarchist and agronomist, was visiting James Mavor, Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, early Shavian and friend of George Bernard Shaw, when the subject of the Doukhobor situation came up. [Some of you may know one of Shaw’s plays called Candida, and it is Mavor who is the professor here].

Mavor had received a letter from Lev Nicolievich describing the unfortunate persecution of the Doukhobors. Kropotkin had traversed the Northwest Territories, [1874-1878] and noted the successful settlements of Hutterites and Mennonites, living peacefully in isolated seclusion, suggested Canada as a suitable destination for the Doukhobors.

Mavor then established a correspondence with Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior, and became Leo Tolstoy’s Canadian connection. As Tolstoy and Tolstoyan sympathizers raised funds and made necessary arrangements in Russia, Mavor negotiated with Clifford Sifton until the first delegation arrived to see the prospective settlement lands in 1897.

In the meantime Chertkov arranged the serialization of Resurrection with the American Cosmopolitan magazine and a prominent Russian journal, with all royalties directed to the immigration fund. Eventually Resurrection realized 17,000 rubles. Lev Nicolievich, who by this time had forsworn royalties for his God given talent, made an exception in this case. He also tapped his wealthy friends and in the end raised about half of the needed funds, 30,000 rubles.

One of the conditions allowing the Doukhobors to leave was that they pay their own way, and of course, few of them had any money. Our Verigin relatives were exceptionally wealthy, having hundreds of sheep and other livestock, as well as a store. All of this was rolled into the common fund, so in effect, our family had helped many of the migrants in their historic migration.

The conclusion of Tolstoy’s assistance and collaboration was the successful emigration of 7,500 Doukhobors to the Northwest Territories in 1899.

Second to Tolstoy was his publisher Vladimir Chertkov, in rallying to the Doukhobor cause. Here is a letter of him writing to George Kennan in the U.S. with an appeal for help:

CHERTKOV LETTERS — Kennan Institute [Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars, Washington DC]

V. Tchertkoff

"Broomfield," Duppas Hill, Croydon

London, Angleterre

10-8-1897

Mr. George Kennan,

My dear Sir,

Your letter dated July 18th gave me much pleasure. I was sincerely glad of the occasion to enter into communication with one towards whom I feel deep esteem and thankfulness for all he has done in the true interests of the Russian people. Besides this I was particularly glad of your kind proposal, we being precisely in need of someone who might interest the American public in the case of the Dukhobortsi, and you are without doubt the most suited to afford this help.

In a week or a fortnight I hope to have in my hands the page proofs of a book upon this subject which I am publishing in England, and I will immediately send you a copy of them. They contain all the information that is required for your purpose and you may use this material in any way you think desirable.

For my part I think the best place would be to print the book in America in its complete form the contents representing a whole and condensed exposition of the case which it would be a pity to take to pieces. The American Edition of the book might be largely circulated amongst the best representatives of the American press, and articles giving reviews of it, and in general concerning the subject might be published in the periodical literature.

The book contains two papers by Leo Tolstoy, [which will add interest in the eyes of the public]. This is only a suggestion on my part, & I perfectly understand that you yourself will be the best judge of how to use the information contained in this book to the best advantage.

As to the agreement with the English publishers of this book, in case you would desire to publish it in America, I will make enquiries, & inform you of the result, when I send you the proof sheets.

Hoping therefore soon to write to you again, allow me to profit by this occasion by wishing you further success in your noble work for the cause of justice and humanity.

Yours very sincerely,

Vladimir Tchertkoff

P.S.

Leo Tolstoy is perfectly ready to be the medium in forwarding relief to the Dukhobortsi but the best way of sending the sums collected would be through us, as such a kind of correspondence by post in Russia may compromise the undertaking, whereas I have means of communicating with Tolstoy through private channels and am continually forwarding to the Spirit Wrestlers our donations which I receive from various quarters.

Broomfield

Duppas Hill

Croydon

——————————--

Dear Mr. Kennan,

By the post I send you our book upon the Spirit Wrestlers, ready for publication. As I stated in my last letter, it would be very desirable to get this book published in America in this complete form. I know of no one in America so fitted as you are to take this in hand, I therefore give it over to you to use your own judgement in regard to it. On my part I have only to say that the English Edition having necessitated expenses, which are not likely soon to be defrayed. I would be glad if the sale of the book in America might help in covering these expenses, & perhaps even bringing in some profits for the cause.

At the same time I would not wish the contents of the book to be sold to any individual as his private property, but I would desire the copyright to be public property.

If the publication is to be undertaken in America the simplest way would be to send over from here the 'moulds' which we shall in any case have in hand. Awaiting your answer both to this letter and to the previous one.

I remain,

Yours most sincerely

V. Tchertkoff

31 August 1897

The copy sent by this post is only for your own private use — we hope every post to receive the entirely corrected proofs I will then send you two copies of these.

Finally we have some select comments from the Makovitskii Diaries:

APRIL 1, 1905: Today L. N. has received a letter from Verigin and Mavor. They want to come, and visit.

L. N.: 'The way - half of the world to go around, Verigin writes that those who distributed the land could not but think and speak about that cattle should be freed from labour and they want to settle to some warmer place, where they could engage themselves in gardening. They think about California, Columbia, they want to go and look even in Australia. In Canada the government and English farmers don't like them, first because they break the law, second because their well being is far ahead of them. English farmers live and work in separate families, they buy the machinery for themselves, and the Doukhobors work in a commune and all together they buy steam engines. [Page 231]

JUNE 12, 1905: L. N. was telling Bulygin about the successes of the Doukhobors in Canada: they are buying dresses for woman from the communal account, milk, flour, are divided by persons.

FEBRUARY 18, 1906: L. N.: Joseph Constantinovich Ditreichs: Canada — is very healthy, there are almost no epidemic diseases there. Remember how Verigin asked one woman and she answered: 'Petyushka, here the babies survive very well, almost never die.'

NOVEMBER 12, 1906: A letter from Chertkov. P. V. Verigin with the others is leaving them for Russia.

DECEMBER 5, 1906: L. N.: I received a telegram from Verigin that they would arrive to-morrow.

DECEMBER 10, 1906: Doukhobors left. L. N.: This time I liked Verigin much more than the previous time. [In 1902]

DECEMBER 11, 1906: At dinner L. N. said that he was reading Verigin's letters from exile. 'They are very good. How intelligent he is!'

L. N. mentioned about Androsov, how once at night he appeared — of huge height in Tcherkess sheep coat, with two sacks. At the door of the Moscow house he was knocking. He was on the way to Verigin to Obdorsk. According to the advice of the editor of Russkie Vedomosti he chose for himself uninhabited trails but the policeman appeared even there where they changed horses for reindeer and he ordered him to return. Izyumchenko invited him to his place and advised him to go further soon. He managed to spend only an hour with Verigin. The policeman appeared and returned him as a prisoner. Then L. N. remembered that he had forgotten to ask the Doukhobors about Pozdnyakov, who had refused to be a Sergeant Major and was tortured. L. N. asked him to show his back: it was all in scars from whipping. He ran away from exile to see his wife, children, and he came to the Caucuses when the Doukhobors were leaving for America. He should have taken the ship and gone away but he returned.

Then L. N. was telling Alexandra Vladimirovna how the Doukhobors went down and when they put on their sheep coats [Verigin didn't have a sheep coat: he presented it on his way to some cold and hungry person; he was wearing a plaid.] — they sang a hymn. Excellent, wonderful!

Sofia Andreevna told Alexandra Vladimironovna about Pyetr Vassil'evich that she has liked him more than she had expected. He told her:'Somehow, you, Sofia Andreevna have become kinder.' And she answered him: 'You have changed.' Sofia Andreevna: There is no self importance in him at all: simple, kind and then she praised the Doukhobors further — what happened from the Russian mujiks! If our Styopky, Adriany, [coachmen] who are drinking wanted to become at least a little better they would behave themselves in a different way.

L. N.: It's impossible a little, you should change completely.

S. A.: [To A. V.]: Why they came, I don't know.

Nikolai Leonidovich: They came, as they said, to thank their friends: in Russia — Lev Nicolievich, in England — Chertkov and Quakers, in Constantinople, to visit the familiar Turks.

L. N.: The Crimean places, a hope to settle there.

S. A.: They are cooking for themselves on a spirit lamp, they are vegetarians for about 12 years. Verigin told me about their holdings, for example, in the village there are about 300 chickens and only 2 women look after them; they receive everything from the storage bins. The main thing is that there is no control and there is no cheating.

As a final note, it is interesting to observe that the Doukhobors had lived together for several hundreds of years with no jails, police or punishment system. Is it any wonder Lev Tolstoy found them admirable and did his utmost to assist them?

————————--

Notes and Bibliography:

Tolstoy Sources:

Address to the Swedish Peace Congress (1909).

Appeal on Behalf of the Doukhobors (March 19, 1898).

Help! Postscript to an appeal to help the Dukhobors persecuted in the Caucasus (December 14, 1896)

Letter on the Peace Conference (January 1899).

Letter to the Doukhobors (beginning from November 6, 1899).

Letter from Tolstoy to Gandhi (September 7, 1910).

Letter to a Corporal (1899).

Letter to the Chief of the Irkútsk Disciplinary Battalion (October 22, 1896).

Letter to Eugen Heinrich Schmitt (October 12, 1896).

Letter to the Editor of "Free Thought", Sofia, Bulgaria (October 17, 1901).

Nobel Bequest (August 29, 1897).

Reminders [also: Notes] for Officers (December 7 or 20, 1901)

Reminders [also: Notes] for Soldiers (December 7 or 20, 1901).

The Beginning of the End — referring to Van-der-Veer, Holland (September 24, 1896 or January 6, 1897).

The Emigration of the Doukhobors (April 1, 1898).

The Persecution of the Doukhobors (September 19, 1885).

Two Wars (August 15 or November 19, 1898).

Who is to Blame? (December 4, 1899).

Books:

Donskov, A. (editor): Leo Tolstoy and Peter Verigin: Correspondence

(Dmitrij Bulanin Publishing House, St. Petersburg, 1995).

Gregory Verigin, God Is Not In Force But In Truth, (Dreyfus & Charpentier, Paris, 1935)

Tolstoy wrote beautifully on this subject in his diary of 1894:

‘No, this world is not a joke, nor merely a valley of temptation one must pass through on the way to a better, eternal world. Rather, it is one of the eternal worlds which is marvellous and joyous and which we not only can but must make even more marvellous and joyous for those around us as well as for those who will continue to live in it after we are gone’.

We can see here their parallel beliefs.

They both believed in the fundamental concept that life on earth was real and in the present, and not as some Christian teachings, a mortal existence as a trial for some future reward in heaven.

In a lecture at the University of Victoria, Dr. Galina Alexeeva, Head of Academic Research at Yasnaya Polyana, State Museum of Leo Tolstoy, noted the highlights of Leo Tolstoy’s life and the highlights in development of the history of the Doukhobors, which began with an early meeting in 1894 in Moscow between Tolstoy and Vasili Verigin, my great grandfather, as Peter was being transported to Siberia, and which culminated in the emigration of the Doukhobors in 1899 with the aid of Leo Tolstoy and his literary legacy.

Although the Doukhobors were basically free hold peasant farmers, some of them belonging to estates, as was the case with our Ewashen family in Tambov, who were only allowed to join their brethren in exile after repeated requests, it is interesting to note that their plight and eventual deliverance emanated from the highest intellectual and bourgeois circles of the day, an international set at that.

Prince Peter Kropotkin, famous anarchist and agronomist, was visiting James Mavor, Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, early Shavian and friend of George Bernard Shaw, when the subject of the Doukhobor situation came up. [Some of you may know one of Shaw’s plays called Candida, and it is Mavor who is the professor here].

Mavor had received a letter from Lev Nicolievich describing the unfortunate persecution of the Doukhobors. Kropotkin had traversed the Northwest Territories, [1874-1878] and noted the successful settlements of Hutterites and Mennonites, living peacefully in isolated seclusion, suggested Canada as a suitable destination for the Doukhobors.

Mavor then established a correspondence with Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior, and became Leo Tolstoy’s Canadian connection. As Tolstoy and Tolstoyan sympathizers raised funds and made necessary arrangements in Russia, Mavor negotiated with Clifford Sifton until the first delegation arrived to see the prospective settlement lands in 1897.

In the meantime Chertkov arranged the serialization of Resurrection with the American Cosmopolitan magazine and a prominent Russian journal, with all royalties directed to the immigration fund. Eventually Resurrection realized 17,000 rubles. Lev Nicolievich, who by this time had forsworn royalties for his God given talent, made an exception in this case. He also tapped his wealthy friends and in the end raised about half of the needed funds, 30,000 rubles.

One of the conditions allowing the Doukhobors to leave was that they pay their own way, and of course, few of them had any money. Our Verigin relatives were exceptionally wealthy, having hundreds of sheep and other livestock, as well as a store. All of this was rolled into the common fund, so in effect, our family had helped many of the migrants in their historic migration.

The conclusion of Tolstoy’s assistance and collaboration was the successful emigration of 7,500 Doukhobors to the Northwest Territories in 1899.

Second to Tolstoy was his publisher Vladimir Chertkov, in rallying to the Doukhobor cause. Here is a letter of him writing to George Kennan in the U.S. with an appeal for help:

CHERTKOV LETTERS — Kennan Institute [Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars, Washington DC]

V. Tchertkoff

"Broomfield," Duppas Hill, Croydon

London, Angleterre

10-8-1897

Mr. George Kennan,

My dear Sir,

Your letter dated July 18th gave me much pleasure. I was sincerely glad of the occasion to enter into communication with one towards whom I feel deep esteem and thankfulness for all he has done in the true interests of the Russian people. Besides this I was particularly glad of your kind proposal, we being precisely in need of someone who might interest the American public in the case of the Dukhobortsi, and you are without doubt the most suited to afford this help.

In a week or a fortnight I hope to have in my hands the page proofs of a book upon this subject which I am publishing in England, and I will immediately send you a copy of them. They contain all the information that is required for your purpose and you may use this material in any way you think desirable.

For my part I think the best place would be to print the book in America in its complete form the contents representing a whole and condensed exposition of the case which it would be a pity to take to pieces. The American Edition of the book might be largely circulated amongst the best representatives of the American press, and articles giving reviews of it, and in general concerning the subject might be published in the periodical literature.

The book contains two papers by Leo Tolstoy, [which will add interest in the eyes of the public]. This is only a suggestion on my part, & I perfectly understand that you yourself will be the best judge of how to use the information contained in this book to the best advantage.

As to the agreement with the English publishers of this book, in case you would desire to publish it in America, I will make enquiries, & inform you of the result, when I send you the proof sheets.

Hoping therefore soon to write to you again, allow me to profit by this occasion by wishing you further success in your noble work for the cause of justice and humanity.

Yours very sincerely,

Vladimir Tchertkoff

P.S.

Leo Tolstoy is perfectly ready to be the medium in forwarding relief to the Dukhobortsi but the best way of sending the sums collected would be through us, as such a kind of correspondence by post in Russia may compromise the undertaking, whereas I have means of communicating with Tolstoy through private channels and am continually forwarding to the Spirit Wrestlers our donations which I receive from various quarters.

Broomfield

Duppas Hill

Croydon

——————————--

Dear Mr. Kennan,

By the post I send you our book upon the Spirit Wrestlers, ready for publication. As I stated in my last letter, it would be very desirable to get this book published in America in this complete form. I know of no one in America so fitted as you are to take this in hand, I therefore give it over to you to use your own judgement in regard to it. On my part I have only to say that the English Edition having necessitated expenses, which are not likely soon to be defrayed. I would be glad if the sale of the book in America might help in covering these expenses, & perhaps even bringing in some profits for the cause.

At the same time I would not wish the contents of the book to be sold to any individual as his private property, but I would desire the copyright to be public property.

If the publication is to be undertaken in America the simplest way would be to send over from here the 'moulds' which we shall in any case have in hand. Awaiting your answer both to this letter and to the previous one.

I remain,

Yours most sincerely

V. Tchertkoff

31 August 1897

The copy sent by this post is only for your own private use — we hope every post to receive the entirely corrected proofs I will then send you two copies of these.

Finally we have some select comments from the Makovitskii Diaries:

APRIL 1, 1905: Today L. N. has received a letter from Verigin and Mavor. They want to come, and visit.

L. N.: 'The way - half of the world to go around, Verigin writes that those who distributed the land could not but think and speak about that cattle should be freed from labour and they want to settle to some warmer place, where they could engage themselves in gardening. They think about California, Columbia, they want to go and look even in Australia. In Canada the government and English farmers don't like them, first because they break the law, second because their well being is far ahead of them. English farmers live and work in separate families, they buy the machinery for themselves, and the Doukhobors work in a commune and all together they buy steam engines. [Page 231]

JUNE 12, 1905: L. N. was telling Bulygin about the successes of the Doukhobors in Canada: they are buying dresses for woman from the communal account, milk, flour, are divided by persons.

FEBRUARY 18, 1906: L. N.: Joseph Constantinovich Ditreichs: Canada — is very healthy, there are almost no epidemic diseases there. Remember how Verigin asked one woman and she answered: 'Petyushka, here the babies survive very well, almost never die.'

NOVEMBER 12, 1906: A letter from Chertkov. P. V. Verigin with the others is leaving them for Russia.

DECEMBER 5, 1906: L. N.: I received a telegram from Verigin that they would arrive to-morrow.

DECEMBER 10, 1906: Doukhobors left. L. N.: This time I liked Verigin much more than the previous time. [In 1902]

DECEMBER 11, 1906: At dinner L. N. said that he was reading Verigin's letters from exile. 'They are very good. How intelligent he is!'

L. N. mentioned about Androsov, how once at night he appeared — of huge height in Tcherkess sheep coat, with two sacks. At the door of the Moscow house he was knocking. He was on the way to Verigin to Obdorsk. According to the advice of the editor of Russkie Vedomosti he chose for himself uninhabited trails but the policeman appeared even there where they changed horses for reindeer and he ordered him to return. Izyumchenko invited him to his place and advised him to go further soon. He managed to spend only an hour with Verigin. The policeman appeared and returned him as a prisoner. Then L. N. remembered that he had forgotten to ask the Doukhobors about Pozdnyakov, who had refused to be a Sergeant Major and was tortured. L. N. asked him to show his back: it was all in scars from whipping. He ran away from exile to see his wife, children, and he came to the Caucuses when the Doukhobors were leaving for America. He should have taken the ship and gone away but he returned.

Then L. N. was telling Alexandra Vladimirovna how the Doukhobors went down and when they put on their sheep coats [Verigin didn't have a sheep coat: he presented it on his way to some cold and hungry person; he was wearing a plaid.] — they sang a hymn. Excellent, wonderful!

Sofia Andreevna told Alexandra Vladimironovna about Pyetr Vassil'evich that she has liked him more than she had expected. He told her:'Somehow, you, Sofia Andreevna have become kinder.' And she answered him: 'You have changed.' Sofia Andreevna: There is no self importance in him at all: simple, kind and then she praised the Doukhobors further — what happened from the Russian mujiks! If our Styopky, Adriany, [coachmen] who are drinking wanted to become at least a little better they would behave themselves in a different way.

L. N.: It's impossible a little, you should change completely.

S. A.: [To A. V.]: Why they came, I don't know.

Nikolai Leonidovich: They came, as they said, to thank their friends: in Russia — Lev Nicolievich, in England — Chertkov and Quakers, in Constantinople, to visit the familiar Turks.

L. N.: The Crimean places, a hope to settle there.

S. A.: They are cooking for themselves on a spirit lamp, they are vegetarians for about 12 years. Verigin told me about their holdings, for example, in the village there are about 300 chickens and only 2 women look after them; they receive everything from the storage bins. The main thing is that there is no control and there is no cheating.

As a final note, it is interesting to observe that the Doukhobors had lived together for several hundreds of years with no jails, police or punishment system. Is it any wonder Lev Tolstoy found them admirable and did his utmost to assist them?

————————--

Notes and Bibliography:

Tolstoy Sources:

Address to the Swedish Peace Congress (1909).

Appeal on Behalf of the Doukhobors (March 19, 1898).

Help! Postscript to an appeal to help the Dukhobors persecuted in the Caucasus (December 14, 1896)

Letter on the Peace Conference (January 1899).

Letter to the Doukhobors (beginning from November 6, 1899).

Letter from Tolstoy to Gandhi (September 7, 1910).

Letter to a Corporal (1899).

Letter to the Chief of the Irkútsk Disciplinary Battalion (October 22, 1896).

Letter to Eugen Heinrich Schmitt (October 12, 1896).

Letter to the Editor of "Free Thought", Sofia, Bulgaria (October 17, 1901).

Nobel Bequest (August 29, 1897).

Reminders [also: Notes] for Officers (December 7 or 20, 1901)

Reminders [also: Notes] for Soldiers (December 7 or 20, 1901).

The Beginning of the End — referring to Van-der-Veer, Holland (September 24, 1896 or January 6, 1897).

The Emigration of the Doukhobors (April 1, 1898).

The Persecution of the Doukhobors (September 19, 1885).

Two Wars (August 15 or November 19, 1898).

Who is to Blame? (December 4, 1899).

Books:

Donskov, A. (editor): Leo Tolstoy and Peter Verigin: Correspondence

(Dmitrij Bulanin Publishing House, St. Petersburg, 1995).

Gregory Verigin, God Is Not In Force But In Truth, (Dreyfus & Charpentier, Paris, 1935)