The Making Of The Doukhobor Suspension Bridge Brilliant B.C.

[HSMBC National Historic Site 1995]

Forced to give up their improved lands in Saskatchewan after new Dominion of Canada policy replaced the Hamlet Clause* in favour of the Homestead Act,** the Doukhobors began their move to B. C. in an effort to preserve their communal life style.

In 1908 Peter V. Verigin, on behalf of the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood,*** purchased the first parcels of land in Waterloo, which he renamed Brilliant, directly across the Columbia River from the present site of Castlegar near the confluence of the Columbia and Kootenay Rivers. Between 1908 and 1913, Doukhobor land holdings in B. C. had grown to over 14,000 acres in this previously virtually uninhabited area. Over 5000 communal members had moved to British Columbia in the hope that life on their own purchased property would lesson government interference in their traditional lifestyle.

By 1911, more than 50,000 fruit trees had been planted and various enterprises were flourishing: lumber yards, brick works, and numerous villages with irrigation systems, complete with their own telephone lines and power generation in the immediate Brilliant area.

Brilliant became the headquarters of the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood. Here the famous Kootenay Columbia Preserving Works was built in 1915 for large scale production of jams and other fruit products. A major centre emerged boasting a packing shed, grain elevator, community store, gas pumps, head office, library, dormitory and dining hall as well as a hospital and Peter Verigin’s residence. Across the road was the CPR railway station with living quarters and the Brilliant Post Office.

Railways were already serving the area. By the turn of the century, a series of lines connected the mines and the smelters between Nelson, the Slocan Valley, Castlegar, Trail, and Rossland. An American line, the Great Northern, ran from the south as far as Nelson. The Canadian Pacific Railway had been extended from the east to the foot of Kootenay Lake.

While rail lines formed the main means of transportation within the West Kootenay region and between it and the outside world, it was essential that roads also be developed for local traffic. By 1912, there was a road from Trail in the south up the west bank of the Columbia to Castlegar near Brilliant. A route also ran from near Nelson in the north down the west bank of the Kootenay to Crescent Valley near the junction of the Slocan River. Much remained to be done to cut through the difficult terrain between the Slocan River and Pass Creek near Brilliant.

The formation of transportation corridors was crucial to the development of the Doukhobors’ rapidly growing settlements in the West Kootenay region. Connections were needed between the various communities and they developed a rudimentary road network at their own expense throughout the 14,000 acres. The major centre of Brilliant was separated from the nearby river communities of Ootishenie by the steep and turbulent Kootenay River. In order to link the communities the Doukhobors established their own ferry driven by a horse and windlass in 1910.

By 1912 Peter 'Lordly' Verigin recognized that the cable ferry was simply not up to the task of the increasing requirement for transportation. There was a need for traversing the Kootenay River that would join the rich orchards and produce gardens and the community of Oootishenie to Brilliant across the Kootenay River in a simple, timely and direct fashion.

Verigin appealed to the B. C. government to have a bridge built, but then as now, there was little response to such requests. Undaunted, he decided the Doukhobor commune would build such a bridge themselves.

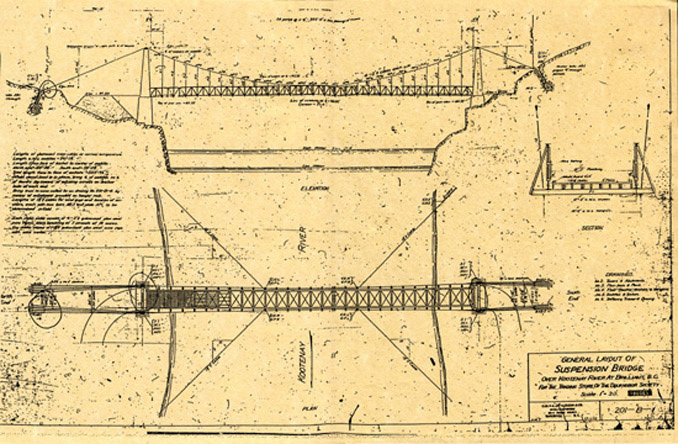

In April 1913 the 'community' or C. C. U. B. embarked on probably its most challenging task to date - to build a bridge across the Kootenay River. Planning and preparation began as early as 1911. Verigin engaged a Vancouver engineering firm, Cartwright, Matheson & Company to devise the plan for the bridge. The firm visited the site and the plan was prepared early 1913 by J. R. Grant, under the supervision of A. M. Truesdale. The firm submitted plans for a suspension wooden bridge or an alternate steel one. Widely used in mountainous areas of North America at the time, this design was well suited for spanning relatively deep and wide gorges and usually resulted in a structure which was light and comparatively economical to erect.

Interviewed in 1992, Harry Voykin of Castlegar, life long member of the Doukhobor commune, remembers: "They went for the steel structure,” explaining that they wanted something that was going to last. The choice was a philosophical one. "It's important for the younger Doukhobor population to see if something is needed, that this wasn't built just for business for the short term. If the people built something it was to last a lifetime,” Voykin goes on.

The workers were of an oral culture whose language was Russian now faced with blueprints drawn up in English. An impossible task? Apparently not.

According to Voykin, "They saw the plan and they built from it. Anything the community started to build they finished.”

Indeed this wasn't the first major project the Doukhobor community had completed. Before the bridge was ever built, Doukhobors had "... built flour mills, a linseed oil press, brick factories, and sawmills as well as their own communal village residences to accommodate 5,000 toilers. They used blueprints and engineers and their own ingenuity,” Voykin says.

On site supervision and advice was also provided by the engineering firm. Peter Reiben, head carpenter, interviewed in 1976, comments on the engineer’s supervision: “The Community paid for everything. Preparation took about a year, and when everything arrived, the engineers sent their helper to supervise construction. He was quite young, maybe about 30 years of age and his task was not easy. The bridge arrived disassembled. Cables had to be cut, the bridge had to be assembled, and everything must be fitted perfectly. It took skill to accomplish this but he was very capable. When the engineer arrived, he began measuring. It was interesting; we thought, how would he measure? Will he use tape or rulers? No. He did all his figuring with a scope. He staked out where we were to begin and from there he would turn and write, turn and write. He determined everything in this manner. When he finished marking things out, we wondered - will all the parts fit together? Will there be enough material? But no, everything was determined perfectly.” The interview continues: “We began at 7:00 a.m. and ended at 6:00 p.m. Eleven hours per day.”

Cyril Ozeroff, [Researcher]: “They were long hours; today one feels tired after working eight hours.”

Mr. Reibin: “Yes, they were long but that is how work in the Community was done. Today, the machines push the worker; one has to work quickly and hard, but at that time, and I was involved in quite a few enterprises after the bridge: building construction, construction of community sawmills, planer mills and others, work was quiet and a person managed quite easily at his job although the hours were long.”

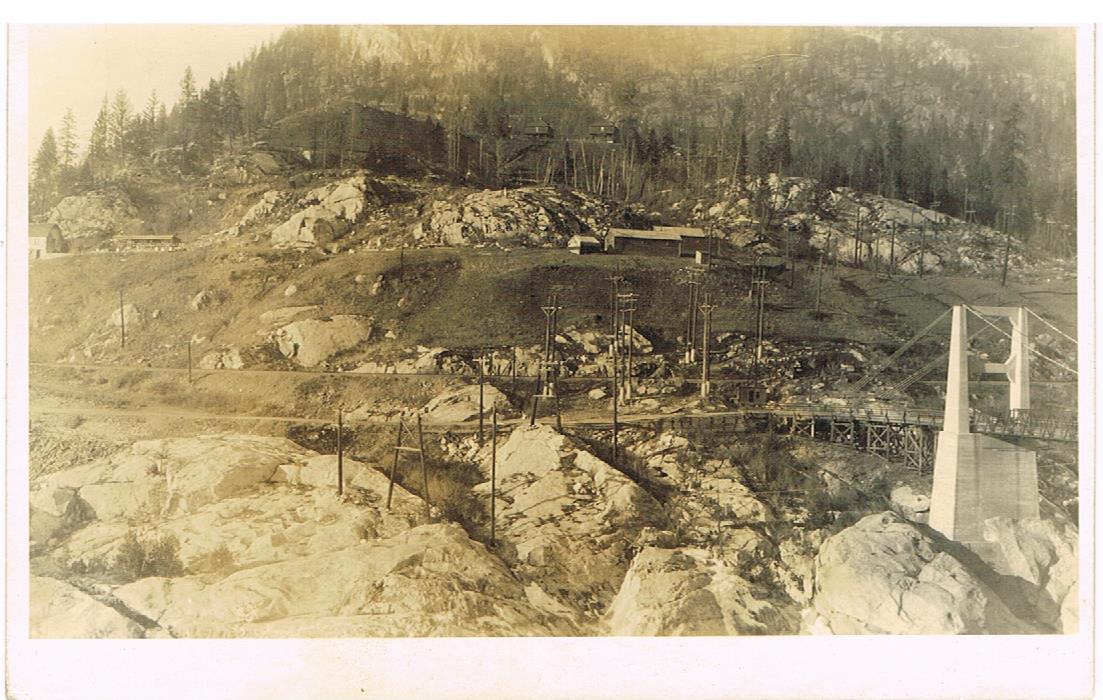

The suspension bridge consisted of reinforced concrete towers, steel wire suspension cables, and a steel deck structure and stiffening trusses. The foundation of the structure consisted of two large concrete piers rising on opposite sides of the river, each monolith supporting two concrete towers rising above the bridge deck. According to Peter Reiben: “I was a carpenter and there were seven more. Four men worked on one side, and four worked on the other. When the tower forms were built up four feet or so, they would be poured, and then we would go higher. When a lower section would set, we would take the boards and use them higher up. The towers tapered toward the top, so we would re-cut the boards to form the tower shape.”

The suspension span is 331 feet in length. At each end of the bridge, the concrete towers rise 48 feet above the road bed. The towers are approximately five feet by ten feet at the bottom and taper to two feet by four feet at the top. The tower legs are connected by cross members also made of concrete. The towers sit on a massive base of concrete about 12 feet thick and 34 feet wide.

The design depended greatly on the strength of the cables, which were suspended from these towers and anchored in the solid rock of the surrounding terrain. Four cables, each two inches in diameter and made of galvanized steel wire, ran the length of the bridge on each side and passed over the tops of the towers by means of saddles supported on rollers. On the banks of the river, the cables were fixed into cast steel sockets with the aid of two, two inch diameter bolts. The bolts were in turn embedded into concrete anchorages sunk about eight feet into the rock faces.

The frame of the bridge deck was constructed of structural steel and suspended from the overhead cables by means of vertical hanger rods, each one inch in diameter. The road surface consisted of a wood deck laid over the metal crossbeams of the span. A layer of large stringers was first laid lengthwise; over it a series of joists ran across the stringers. Finally, the flooring consisted of four inch by ten inch planking laid lengthwise. This created a road surface of about fourteen feet in width suspended approximately sixty feet in height above the high water mark.

Several standardized techniques were used to strengthen the deck to prevent it from moving under great weight or in high winds. Steel stiffening trusses were mounted on each side of the bridge extending above the level of the roadway, interspersed with vertical posts. The bridge also employed four wind guys of galvanized steel wire, two on each side running from near the middle of the deck to the riverbanks where they were sunk into concrete. Cement was imported from Spokane and hand-mixed.

The Brilliant Bridge was similar to other suspension structures being built in British Columbia with one notable exception; it incorporated reinforced concrete in the tower foundations. Use of strengthened concrete for structural purposes was only being introduced into bridge design and was rarely used before the first World War. By the 1920s, reinforced concrete was to become the material of choice among bridge builders. The Brilliant bridge was near the cutting edge of design. An engineer and bridge historian who studied the bridge prior to the restoration, said: ‘From the condition of the towers after nearly eighty years in service, the designers and builders had a much better appreciation of concrete construction than was usual at that date’. It was this key factor that rendered the bridge fit for restoration nearly one hundred years after initial construction.

Construction began in April 1913, and went on for seven months. Although the bridge was built without outside hired help, the impressive construction job wasn't without other costs. Material and engineering fees amounted to $60,000. Forty Doukhobors were the on site work party, hundreds of others did supply and parts work. The bridge was completed in October, 1913.

Peter Reibin elaborates on the step by step process of the construction: Work began with the towers. Carpenters built wooden forms into which the concrete was poured. Scaffolding facilitated work on the columns as they rose higher. On the Brilliant side of the river, poles were erected and the cement was hoisted by elevator with the aid of a donkey engine. On the Ooteshenie side, there was much less room. The engineer arranged for a large derrick with a boom and a bucket which held two wheelbarrows of cement. The boom would swing from the cement mixer to the wooden forms where the concrete was poured.

Much of the initial assembly began on the Brilliant side of the river. Here the cables were laid out, measured for length, and cut. After the cables were suspended, the artisans and labourers started to work on segments of the bridge decking. On the advice of the engineer, they drilled holes for bolts and made some adjustments in the slight arching planned for the span. The next stage of the job was the most difficult: that of moving the deck sections into position on the bridge. Peter Reibin goes on: When the cables were in place at the river, the bridge segments were moved to the river for final assembly. A cable was strung a little higher than the others and four men, two on each side at the end of the bridge, sitting on small seats which were fastened to the cable, hooked rods first to the large cables and then to the bridge frame. This was one of the more dangerous jobs. After the rods were fastened, rails were bolted to the steel crossbeams. After three or so cross beams were in place we would proceed with the bridge deck; stringers, joists and flooring. We worked from both ends of the bridge in sections until both sides came together.

Noting the Doukhobors’ determination and successful result, and realizing that this bridge would be used by the entire growing community, although it was clearly intended mainly for the use of the Doukhobors who took the responsibility for its upkeep, the provincial government contributed $19,500 towards the construction.****

Peter Reiben explains in the 1976 interview: “All the work at that time was by hand; there were no machines. We had a gasoline cement mixer for mixing cement and in cases of lifting something heavy such as cement, a donkey engine was used for power.”

According to the position paper as prepared by the supervising firm there were no injuries during the construction. However, on the ground research indicates deaths connected with the enterprise.

Harry Voykin reflects on this difficult achievement: “As a monument, it is a reminder of the people who died working on the project, and at least seven others who were severely injured. Some 100 people used their hands to create the structure. No heavy machinery or electricity was used. Those people made their own hammers and axes, even the level used to make sure the structure was level was homemade. Everything was done with their hands, with wheelbarrows. The government refused to do it so we found some architects and started building the bridge.”

From the Doukhobor Discovery Centre archives we have a transcript of Helen Verigin interviewing John Fomenoff in 1974. John arrived on the Lake Huron in 1899, the first ship carrying the 7,500 refugees from Russia: “I remember the Brilliant bridge being built. At the time I was working at the Brilliant sawmill. The Doukhobors hewed out the road leading up to it and then cemented blocks, strung the cable and planked it. When they were hewing the road out a strange thing happened. A rock at least twenty tons slid from above right over the working crew, everyone ran except John Samsonoff who wasn’t fast enough to pick up his crowbar and run. The rock slid right over him and over the bank into the river. The other men ran up to him and he got up and walked away. After investigating they found that as the road wasn't finished the rocks jutting out of the road were high enough that they balanced the big rock and left enough space underneath for John, not to even touch him. The crowbar was like a pretzel.”

A fortunate escape from near disaster, but he goes on to describe a tragic event: “When they were blasting for the bridge, the dynamite was cold and damp. Sometimes it would explode and sometimes not. The men started drying it in the electric pump house that was on the Ootishenie side. John Sherbinin warned them that it was dangerous, yet the men continued to do it. One day the dynamite exploded in the pump house and some were injured, some died. Strukoff was blasted right into the door. Other men that were in there were Strukoff’s brother John, Alex Reibin, Mike Labentsoff. He was deaf from then on and four died. We hitched a team at the sawmill and went to help. They were bringing out the wounded and the dead. Who knows what really happened there . . ."

The Brilliant Suspension Bridge opened officially in October 1913 with the entire community, singing psalms and trekking from either side to meet in the middle where Peter Verigin proffered a benediction.

The frame of the bridge deck was constructed of structural steel and suspended from the overhead cables by means of vertical hanger rods, each one inch in diameter. The road surface consisted of a wood deck laid over the metal crossbeams of the span. A layer of large stringers was first laid lengthwise; over it a series of joists ran across the stringers. Finally, the flooring consisted of four inch by ten inch planking laid lengthwise. This created a road surface of about fourteen feet in width suspended approximately sixty feet in height above the high water mark.

Several standardized techniques were used to strengthen the deck to prevent it from moving under great weight or in high winds. Steel stiffening trusses were mounted on each side of the bridge extending above the level of the roadway, interspersed with vertical posts. The bridge also employed four wind guys of galvanized steel wire, two on each side running from near the middle of the deck to the riverbanks where they were sunk into concrete. Cement was imported from Spokane and hand-mixed.

The Brilliant Bridge was similar to other suspension structures being built in British Columbia with one notable exception; it incorporated reinforced concrete in the tower foundations. Use of strengthened concrete for structural purposes was only being introduced into bridge design and was rarely used before the first World War. By the 1920s, reinforced concrete was to become the material of choice among bridge builders. The Brilliant bridge was near the cutting edge of design. An engineer and bridge historian who studied the bridge prior to the restoration, said: ‘From the condition of the towers after nearly eighty years in service, the designers and builders had a much better appreciation of concrete construction than was usual at that date’. It was this key factor that rendered the bridge fit for restoration nearly one hundred years after initial construction.

Construction began in April 1913, and went on for seven months. Although the bridge was built without outside hired help, the impressive construction job wasn't without other costs. Material and engineering fees amounted to $60,000. Forty Doukhobors were the on site work party, hundreds of others did supply and parts work. The bridge was completed in October, 1913.

Peter Reibin elaborates on the step by step process of the construction: Work began with the towers. Carpenters built wooden forms into which the concrete was poured. Scaffolding facilitated work on the columns as they rose higher. On the Brilliant side of the river, poles were erected and the cement was hoisted by elevator with the aid of a donkey engine. On the Ooteshenie side, there was much less room. The engineer arranged for a large derrick with a boom and a bucket which held two wheelbarrows of cement. The boom would swing from the cement mixer to the wooden forms where the concrete was poured.

Much of the initial assembly began on the Brilliant side of the river. Here the cables were laid out, measured for length, and cut. After the cables were suspended, the artisans and labourers started to work on segments of the bridge decking. On the advice of the engineer, they drilled holes for bolts and made some adjustments in the slight arching planned for the span. The next stage of the job was the most difficult: that of moving the deck sections into position on the bridge. Peter Reibin goes on: When the cables were in place at the river, the bridge segments were moved to the river for final assembly. A cable was strung a little higher than the others and four men, two on each side at the end of the bridge, sitting on small seats which were fastened to the cable, hooked rods first to the large cables and then to the bridge frame. This was one of the more dangerous jobs. After the rods were fastened, rails were bolted to the steel crossbeams. After three or so cross beams were in place we would proceed with the bridge deck; stringers, joists and flooring. We worked from both ends of the bridge in sections until both sides came together.

Noting the Doukhobors’ determination and successful result, and realizing that this bridge would be used by the entire growing community, although it was clearly intended mainly for the use of the Doukhobors who took the responsibility for its upkeep, the provincial government contributed $19,500 towards the construction.****

Peter Reiben explains in the 1976 interview: “All the work at that time was by hand; there were no machines. We had a gasoline cement mixer for mixing cement and in cases of lifting something heavy such as cement, a donkey engine was used for power.”

According to the position paper as prepared by the supervising firm there were no injuries during the construction. However, on the ground research indicates deaths connected with the enterprise.

Harry Voykin reflects on this difficult achievement: “As a monument, it is a reminder of the people who died working on the project, and at least seven others who were severely injured. Some 100 people used their hands to create the structure. No heavy machinery or electricity was used. Those people made their own hammers and axes, even the level used to make sure the structure was level was homemade. Everything was done with their hands, with wheelbarrows. The government refused to do it so we found some architects and started building the bridge.”

From the Doukhobor Discovery Centre archives we have a transcript of Helen Verigin interviewing John Fomenoff in 1974. John arrived on the Lake Huron in 1899, the first ship carrying the 7,500 refugees from Russia: “I remember the Brilliant bridge being built. At the time I was working at the Brilliant sawmill. The Doukhobors hewed out the road leading up to it and then cemented blocks, strung the cable and planked it. When they were hewing the road out a strange thing happened. A rock at least twenty tons slid from above right over the working crew, everyone ran except John Samsonoff who wasn’t fast enough to pick up his crowbar and run. The rock slid right over him and over the bank into the river. The other men ran up to him and he got up and walked away. After investigating they found that as the road wasn't finished the rocks jutting out of the road were high enough that they balanced the big rock and left enough space underneath for John, not to even touch him. The crowbar was like a pretzel.”

A fortunate escape from near disaster, but he goes on to describe a tragic event: “When they were blasting for the bridge, the dynamite was cold and damp. Sometimes it would explode and sometimes not. The men started drying it in the electric pump house that was on the Ootishenie side. John Sherbinin warned them that it was dangerous, yet the men continued to do it. One day the dynamite exploded in the pump house and some were injured, some died. Strukoff was blasted right into the door. Other men that were in there were Strukoff’s brother John, Alex Reibin, Mike Labentsoff. He was deaf from then on and four died. We hitched a team at the sawmill and went to help. They were bringing out the wounded and the dead. Who knows what really happened there . . ."

The Brilliant Suspension Bridge opened officially in October 1913 with the entire community, singing psalms and trekking from either side to meet in the middle where Peter Verigin proffered a benediction.

The bridge became popular for public use as well as for the Doukhobors. Noting that hunters and smokers were using the bridge, about six months after completion the Doukhobors responded by placing a famous sign on it which read: STRICTLY PROHIBITED SMOKING AND TRESPASSING WITH FIREARMS OVER THIS BRIDGE, which became a well known expression of their principles.*****

In 1922 when economic times were becoming difficult and noting that the Doukhobor built roads were being used by the general public not only in Castlegar but In Grand Forks, Peter Verigin appealed to the B. C. government for $30,000. compensation for the bridge and the roads now in public use. No additional compensation was forthcoming.

Initially the bridge was intended for horse drawn carriages and cartage wagons, in later years it carried heavier traffic. "It was built strong enough for logging trucks and Greyhound buses,” a smiling Voykin says. "The bridge was used even more in the last years of its existence [after foreclosure] until the current bridge was built in 1966."

Despite sociological and economic strains of the era, the C.C.U.B. enjoyed prosperous times. This ended however, in 1938, when the Sun Life Assurance Company, Great West Mortgage, Canadian Imperial Bank and National Trust moved to foreclose on the enterprise over their inability to pay $300,000. interest on an expansion loan on time. The Farm Credit Corporation had been formed to keep agriculture thriving because of food shortages, but in this case, inexplicably denied any assistance. The provincial government was willing and perhaps even eager to see the collapse of an institution which they considered foreign and bothersome and they also saw an advantage to this foreclosure. As a result, the government did nothing to prevent the foreclosure of the CCUB, but did act to prevent the social problem which would have resulted from thousands of Doukhobors being thrown off their land once again. To avoid this, in 1939, the province moved to purchase the communal property for a fraction of the original cost with the scheme of renting it back to the people living on it. The provincial government paid a negotiated sum of $280,000., and thus became the new 'owner' of the largest communal enterprise in North America, comprised of 71,600 acres throughout the three western provinces and industries evaluated at $11,000,000. However, it had no intention of preserving the integral structure of the commune and proceeded to liquidate all assets, presumably to receive compensation for the $280,000. Neither did it allow the Doukhobors to remain on their former property if they were unable to pay rent. Those who were not able to pay, mostly now unemployed and seniors, faced eviction.

All lands and assets became the property of the Province of British Columbia and the Brilliant Suspension Bridge was co-opted by the Department of Highways. Poised between the communities of Brilliant and Ooteshenie, the bridge had played an important role as part of the Doukhobor economic network and the local transportation system for more than 25 years, but now its Doukhobor ownership was over.

In 1957 it facilitated the development of the Castlegar airport, an irony since the development of the airport also included the expropriation of 12 Doukhobor villages which were bulldozed.

In 1961, all Doukhobor properties were put on sale, items for public use such as schools, roads and bridges, remained under government ownership. The bridge continued to serve the public until 1966 when a new bridge was constructed to facilitate the growing needs of the nearby communities and airport access, all important to Castlegar's growing economic development.

It continued to be used for pedestrian traffic until it deteriorated to such a degree that it was considered a hazard and was barricaded to prevent access and possible injury. Consequently, it sat dormant for many years. In the 1970s it was discovered that the Department of Highways planned to demolish this historic structure as they considered it a public hazard. Past Mayor of Castlegar, Mike O'Connor, tells how, in a truly eleventh-hour plea to the provincial government, the bridge was saved from almost certain demise when he appeared personally in Victoria, showing historical cause as to why the bridge should not be destroyed. The provincial government relented and demolition was staved off.

First nominated by Pete Oglow on June 29, 1994, the bridge was designated as an Historic Monument in 1995 by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, a Centennial year for the Doukhobors.******

Andy Davidoff, past coordinator of the Restoration Committee said: "The bridge represents the noble efforts of a pioneering culture and remains a symbolic relic and witness of that. Naturally, the cultural group affected strongly desires that the bridge be restored and not be dismantled as is its only destiny if nothing is done to preserve it."

In 1991 a Working Group was assembled to explore the possibilities of restoring the bridge. The bridge restoration committee collected some funds and kept the idea of restoration alive for some years but there was little noticeable progress until the author of this article made a motion in a Council of Doukhobors meeting to reactivate the project. He also restarted negotiations with the HSMBC to determine a final plaque wording. This was duly completed with the participation of the Council of Doukhobors in Canada.

Lawrence Makortoff, whose grandfather had worked on the original structure, took the lead in fund raising, ably assisted by Gordon Zaitsoff, representative to the Regional District. The Regional District took over the ownership. Considerable support for its restoration came not only from Doukhobors, but also from politicians and others in the region interested in heritage preservation. The provincial government extended recognition and contributed funding for the restoration of the structure. B. C. Hydro funded a comprehensive study of the structural components. Engineering studies were completed by Cominco Engineering Services and Inter-Mountain Testing Limited found the structure basically sound.

The cause was just and fund raising was successful, and the restored and renovated bridge had a second official opening in 2010. Restoration had cost nearly $1,000.000. In co-operation with several levels of government, the working group is planning a regional park in which the bridge will play a central role as an historical element and as part of an extensive walking trail network of the Trans-Canada Trail.

Winston Churchill said that the farther back we look, the more clearly we can see the future. As a symbol of the Doukhobor people with the motto of Toil and Peaceful Life which encapsulated the concept of peaceful coexistence with all living things and nature, it is a worthwhile symbol and a beacon for these concepts whose time is long overdue.

The bridge plaque, unveiled at the Doukhobor Discovery Centre, May 1st, 2008, reads in English, French, and Russian:

The official HSMBC plaque:

DOUKHOBOR SUSPENSION BRIDGE

This historic bridge commemorates an achievement of the Doukhobors of Canada in establishing communal settlements in the Kootenay Boundary Region of British Columbia during the early 20th century. Built in 1913 by community labour, the bridge connected Doukhobor settlements on both sides of the Kootenay River, and served as a vital transportation link in the area for over fifty years. Today, this structure, also known as the Brilliant Suspension Bridge, stands as an enduring symbol of the collective toil of these Christian pacifist pioneers, and their contribution to Canada's development.

This historic bridge commemorates an achievement of the Doukhobors of Canada in establishing communal settlements in the Kootenay Boundary Region of British Columbia during the early 20th century. Built in 1913 by community labour, the bridge connected Doukhobor settlements on both sides of the Kootenay River, and served as a vital transportation link in the area for over fifty years. Today, this structure, also known as the Brilliant Suspension Bridge, stands as an enduring symbol of the collective toil of these Christian pacifist pioneers, and their contribution to Canada's development.

HSMBC unveiling group:

Plaque Unveiling: Posing from left to right: Doreen McGillis, Senior Communications Officer, Parks Canada/Mount Revelstoke and Glacier Field Unit, Larry Ewashen, Curator, Elizabeth (Betty) Sloan (representing Parks Canada), Manager of Finance and Administration, Parks Canada/Mount Revelstoke and Glacier Field Unit Terrence (Terry) Foster, (Master of Ceremony, representing the Historic Sites and Monument Board of Canada) and Brian Higgins, Senior Park Warden, responsible for Cultural Resources Management, Parks Canada/Mount Revelstoke and Glacier Field Unit.

Footnotes:

* The Hamlet clause was created to enable communal settling groups to be granted land in a bloc with the settlers living in communal villages near by the land under improvement.

** The Homestead Act required individual settlement and cultivation by the claimant on each 160 acres and a registration fee and Oath of Allegiance for entitlement. In 1907 Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, used this act to coerce assimilation of the communal groups.

*** The official company of the Doukhobors, The Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, was incorporated in 1917 with a capital of $1,000,000. although their assets were far greater by that time.

**** Public Works Reports 1912-3 and 1913-4, pp.13, 25, 26, The government of British Columbia contributed 10,000 dollars toward the cost of the bridge in the fiscal year 1912-3, and 9,500 in 1913-4 (Sessional Papers, British Columbia).

***** Doukhobors did not drink or smoke in view of the belief that God lived within all. Consequently, as pacifists, they had burned their weapons in 1895, an event which precipitated their refuge to Canada because of the sever persecution which followed. Smoking could also cause a possible fire on the bridge planking.

****** 1995 was the 100th anniversary of the famous Doukhobor Arms Burning which took place in Russia in 1895.

References:

Presentation of November 20, 2006 by Lawrence Makortoff to City of Castlegar, Mayor and Council - a compelling argument advocating the area's involvement in the bridge's restoration.

Castlegar Citizen - August 25/04 - News Article describing the restoration project.

Castlegar News - September 29/04 - U B. C.M meeting in Kelowna coverage.

Letter August 20/04 - letter from Mayor Mike O'Connor to John Mansbridge, Castlegar Parks & Trails Society.

1995 Agenda Paper written by Dr. William Wylie, Historical Services Branch, and accompanied by a request that the Brilliant Bridge be considered as a National Historic Site (Courtesy of the Doukhobor Discovery Centre).

1976 Cyril Ozeroff [whose grandfather had worked on the construction] Term Paper, an excellent resource on the building of the Brilliant Bridge. Ozeroff received an A+ for his account (Courtesy of the Doukhobor Discovery Centre).

Castlegar News, November 4, 1992, feature page entitled: 'Our People' Bridge Over Troubled Water: Corinna Jackson, news reporter.

Letter, Pete Oglow, Director, Kootenay Doukhobor Historical Society, Castlegar, to Dr. Christina Cameron, Director General, National Historic Sites Directorate, 29 June 1994.

Nelson News, 12 June 1912, quoted in ibid., p. 11; "General Layout of Suspension Bridge over Kootenay River at Brilliant, B.C.".

Work records, Cartwright, Matheson and Co., Engineers, Vancouver, B.C., 17 January 1913

Robert W. Passfield, "The Lillooet Suspension Bridge, Fraser River, British Columbia," Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, Agenda Papers, 1982, p. 366.

William M. Rozinkin, "Historic Old Brilliant Bridge Soon to Disappear - Had Important Role in History of Area,” from the Nelson Daily News, 10 June 1966.

Cowell, "Brilliant Suspension Bridge - A Brief Historical Perspective,” Engineering Dimensions, March-April 1987, pp. 34-5.

Jasper O. Draffin, "A Brief History of Lime, Cement, Concrete and Reinforced Concrete," Journal of the Western Society of Engineers, Volume 48 (March, 1943), pp.4-14

Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, minutes, November 1982, p. 16 and June 1986, p. 27.

* The Hamlet clause was created to enable communal settling groups to be granted land in a bloc with the settlers living in communal villages near by the land under improvement.

** The Homestead Act required individual settlement and cultivation by the claimant on each 160 acres and a registration fee and Oath of Allegiance for entitlement. In 1907 Frank Oliver, Minister of the Interior, used this act to coerce assimilation of the communal groups.

*** The official company of the Doukhobors, The Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, was incorporated in 1917 with a capital of $1,000,000. although their assets were far greater by that time.

**** Public Works Reports 1912-3 and 1913-4, pp.13, 25, 26, The government of British Columbia contributed 10,000 dollars toward the cost of the bridge in the fiscal year 1912-3, and 9,500 in 1913-4 (Sessional Papers, British Columbia).

***** Doukhobors did not drink or smoke in view of the belief that God lived within all. Consequently, as pacifists, they had burned their weapons in 1895, an event which precipitated their refuge to Canada because of the sever persecution which followed. Smoking could also cause a possible fire on the bridge planking.

****** 1995 was the 100th anniversary of the famous Doukhobor Arms Burning which took place in Russia in 1895.

References:

Presentation of November 20, 2006 by Lawrence Makortoff to City of Castlegar, Mayor and Council - a compelling argument advocating the area's involvement in the bridge's restoration.

Castlegar Citizen - August 25/04 - News Article describing the restoration project.

Castlegar News - September 29/04 - U B. C.M meeting in Kelowna coverage.

Letter August 20/04 - letter from Mayor Mike O'Connor to John Mansbridge, Castlegar Parks & Trails Society.

1995 Agenda Paper written by Dr. William Wylie, Historical Services Branch, and accompanied by a request that the Brilliant Bridge be considered as a National Historic Site (Courtesy of the Doukhobor Discovery Centre).

1976 Cyril Ozeroff [whose grandfather had worked on the construction] Term Paper, an excellent resource on the building of the Brilliant Bridge. Ozeroff received an A+ for his account (Courtesy of the Doukhobor Discovery Centre).

Castlegar News, November 4, 1992, feature page entitled: 'Our People' Bridge Over Troubled Water: Corinna Jackson, news reporter.

Letter, Pete Oglow, Director, Kootenay Doukhobor Historical Society, Castlegar, to Dr. Christina Cameron, Director General, National Historic Sites Directorate, 29 June 1994.

Nelson News, 12 June 1912, quoted in ibid., p. 11; "General Layout of Suspension Bridge over Kootenay River at Brilliant, B.C.".

Work records, Cartwright, Matheson and Co., Engineers, Vancouver, B.C., 17 January 1913

Robert W. Passfield, "The Lillooet Suspension Bridge, Fraser River, British Columbia," Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, Agenda Papers, 1982, p. 366.

William M. Rozinkin, "Historic Old Brilliant Bridge Soon to Disappear - Had Important Role in History of Area,” from the Nelson Daily News, 10 June 1966.

Cowell, "Brilliant Suspension Bridge - A Brief Historical Perspective,” Engineering Dimensions, March-April 1987, pp. 34-5.

Jasper O. Draffin, "A Brief History of Lime, Cement, Concrete and Reinforced Concrete," Journal of the Western Society of Engineers, Volume 48 (March, 1943), pp.4-14

Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, minutes, November 1982, p. 16 and June 1986, p. 27.