BOOK REVIEWS

Featuring various books as they appear:

The Chronicles of Spirit Wrestlers’ Immigration to Canada.

God is not in Might, but in Truth

Grigorii Visil’evich Verigin

Edited by Veronika Makarova, Larry A. Ewashen

Translated by Veronika Makarova

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

2019, XXIII+ 304 pp., Hardcover

ISBN 978-3-030-18524-4

There are believers whose custom it is to bow low before every person with whom they come into contact. They say they do this because in every individual dwells the Spirit of God. No matter how strange this custom may seem, it is based on a profound truth.

[L N. Tolstoy, Krug Chtenija [Cycle of readings], Polnoe sobranie sochinenij: Jubilejnoe izdanie [Complete collected works: Jubilee edition] (Moscow: Goslitizdat, 1928-58), Vol. 41, p. 202]

This statement, even though not referring explicitly to the Doukhobors, is significant for the purposes of any study of the group. First, it is one of Tolstoy’s personal observations included in his collection of beloved aphorisms, published under the title Cycle of Readings. He wrote it in the twilight of his life, after knowing and being actively involved with the Doukhobor movement for almost twenty years. It refers to a collective rather than to individual dissidents as he had written about in the past. Most importantly, it shows a reverence for the truth it proclaims regarding the relationship of human beings to each other and to God.

This is precisely the major tenet of Grigorii Vasil’evich Verigin’s book, which chronicles the history of the Doukhobors, and that from, what is of seminal importance, from an insider’s perspective. As the editors note, he was not only a witness to Doukhobor persecution and suffering in Russia, but also a recipient of these sufferings himself. The narrative covers the historical evolvement of this group from their earliest origin, through their oppression carried on by the Russian state and Church in the 19th Century, to their eventual settling in Canada, the hardships they had to deal with here, to the tragic death in 1924 of Grigorii’s older brother Petr Vasil’evich Verigin. It is a gripping account of these peoples’ condemnation of militarism, conflict and violence and their unwavering pursuit of pacifism. Small wonder that Leo Tolstoy held them in high esteem and referred to them as the “people of the 25th Century.”

Prefaced by the Translator and the Editors, by Pavel Biriukov’s (the Editor of the original publication in Russian) sensitive summary of Doukhobor experiences, and by Grigorii Verigin’s brief Introduction, the book is divided into forty-three chapters, three addenda, name index and subject index. Through recollections, personal experiences and involvement, sharp analysis, and as a person closely familiar with his subject, Grigorii writes a compelling account of his elder brother’s life while both in Russia and Canada. He supports and documents his claim that his brother had enormous leadership qualities, resilience, fervent desire to serve his people, to avoid and combat the evil. Some of these documents are reproduced in the book. Each chapter is a unit unto itself, yet the transitions to the next are natural and smooth. I particularly found moving ch. 40 (pp. 245-258), a visit in 1914 to the Doukhobor community by several ministers and dignitaries, entitled “A Conversation Between Military [sic] Minister Bowser and the Doukhobors "About Registries and Schools,” outlining basic Doukhobor beliefs. In addition to

discussing major characteristics of Doukhobor faith and philosophy, we also learn of many individuals, and groups of people, places and day-to-day struggles and hopes in the lives of these inhabitants.

According to the editors, G. Verigin’s manuscript was completed in 1929-1930 and “subsequently sent for publication to Pavel Ivanovich Biriukov, who arranged publication in France.”

This immensely important work had to wait some ninety years to be translated in full into English and edited according to our standards. In both of these areas, it excels. Dr. Veronika Makarova, an eminent linguist (University of Saskatchewan) did a commendable job in rendering often difficult language, turns of phrases, concise folk expressions and local dialect into a racy English idiom and Larry Ewashen, the stalwart and the indefatigable keeper and researcher of the Doukhobor philosophy, provided his comprehensive knowledge in editing the text and providing sufficiently detailed, but not intrusive, annotations and commentaries on names, places and events.

The editors decided to provide a new title for the book: “The Chronicles of Spirit Wrestlers’ Immigration to Canada”, and use the original title “God is not in Might, but in Truth” (Ne v Sile Bog, a v Pravde) as a subtitle. This was probably a more encompassing name, readily understood by a substantial segment of Canadian Doukhobors. I am thinking here especially of present and future Doukhobor descendants who have been prevented by the inevitable assimilating influences of their environment from fully keeping up with the language of their forebears, as well as all English-speaking Canadians who wish to become acquainted with a noteworthy contribution to the history of this country.

This edition will provide most useful, indeed, indispensable material for scholars and students concerned with contemporary issues in this unsettled world, especially for those dealing seriously with social, religious, philosophical and historical studies. Title: Distinguished University Professor

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada

Dr. Andrew Donskov

Department of Languages and Literatures

University of Ottawa

Ottawa, ON

K1N 6N5

Distinguished University Professor

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada

The Chronicles of Spirit Wrestlers’ Immigration to Canada.

God is not in Might, but in Truth

Grigorii Visil’evich Verigin

Edited by Veronika Makarova, Larry A. Ewashen

Translated by Veronika Makarova

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

2019, XXIII+ 304 pp., Hardcover

ISBN 978-3-030-18524-4

There are believers whose custom it is to bow low before every person with whom they come into contact. They say they do this because in every individual dwells the Spirit of God. No matter how strange this custom may seem, it is based on a profound truth.

[L N. Tolstoy, Krug Chtenija [Cycle of readings], Polnoe sobranie sochinenij: Jubilejnoe izdanie [Complete collected works: Jubilee edition] (Moscow: Goslitizdat, 1928-58), Vol. 41, p. 202]

This statement, even though not referring explicitly to the Doukhobors, is significant for the purposes of any study of the group. First, it is one of Tolstoy’s personal observations included in his collection of beloved aphorisms, published under the title Cycle of Readings. He wrote it in the twilight of his life, after knowing and being actively involved with the Doukhobor movement for almost twenty years. It refers to a collective rather than to individual dissidents as he had written about in the past. Most importantly, it shows a reverence for the truth it proclaims regarding the relationship of human beings to each other and to God.

This is precisely the major tenet of Grigorii Vasil’evich Verigin’s book, which chronicles the history of the Doukhobors, and that from, what is of seminal importance, from an insider’s perspective. As the editors note, he was not only a witness to Doukhobor persecution and suffering in Russia, but also a recipient of these sufferings himself. The narrative covers the historical evolvement of this group from their earliest origin, through their oppression carried on by the Russian state and Church in the 19th Century, to their eventual settling in Canada, the hardships they had to deal with here, to the tragic death in 1924 of Grigorii’s older brother Petr Vasil’evich Verigin. It is a gripping account of these peoples’ condemnation of militarism, conflict and violence and their unwavering pursuit of pacifism. Small wonder that Leo Tolstoy held them in high esteem and referred to them as the “people of the 25th Century.”

Prefaced by the Translator and the Editors, by Pavel Biriukov’s (the Editor of the original publication in Russian) sensitive summary of Doukhobor experiences, and by Grigorii Verigin’s brief Introduction, the book is divided into forty-three chapters, three addenda, name index and subject index. Through recollections, personal experiences and involvement, sharp analysis, and as a person closely familiar with his subject, Grigorii writes a compelling account of his elder brother’s life while both in Russia and Canada. He supports and documents his claim that his brother had enormous leadership qualities, resilience, fervent desire to serve his people, to avoid and combat the evil. Some of these documents are reproduced in the book. Each chapter is a unit unto itself, yet the transitions to the next are natural and smooth. I particularly found moving ch. 40 (pp. 245-258), a visit in 1914 to the Doukhobor community by several ministers and dignitaries, entitled “A Conversation Between Military [sic] Minister Bowser and the Doukhobors "About Registries and Schools,” outlining basic Doukhobor beliefs. In addition to

discussing major characteristics of Doukhobor faith and philosophy, we also learn of many individuals, and groups of people, places and day-to-day struggles and hopes in the lives of these inhabitants.

According to the editors, G. Verigin’s manuscript was completed in 1929-1930 and “subsequently sent for publication to Pavel Ivanovich Biriukov, who arranged publication in France.”

This immensely important work had to wait some ninety years to be translated in full into English and edited according to our standards. In both of these areas, it excels. Dr. Veronika Makarova, an eminent linguist (University of Saskatchewan) did a commendable job in rendering often difficult language, turns of phrases, concise folk expressions and local dialect into a racy English idiom and Larry Ewashen, the stalwart and the indefatigable keeper and researcher of the Doukhobor philosophy, provided his comprehensive knowledge in editing the text and providing sufficiently detailed, but not intrusive, annotations and commentaries on names, places and events.

The editors decided to provide a new title for the book: “The Chronicles of Spirit Wrestlers’ Immigration to Canada”, and use the original title “God is not in Might, but in Truth” (Ne v Sile Bog, a v Pravde) as a subtitle. This was probably a more encompassing name, readily understood by a substantial segment of Canadian Doukhobors. I am thinking here especially of present and future Doukhobor descendants who have been prevented by the inevitable assimilating influences of their environment from fully keeping up with the language of their forebears, as well as all English-speaking Canadians who wish to become acquainted with a noteworthy contribution to the history of this country.

This edition will provide most useful, indeed, indispensable material for scholars and students concerned with contemporary issues in this unsettled world, especially for those dealing seriously with social, religious, philosophical and historical studies. Title: Distinguished University Professor

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada

Dr. Andrew Donskov

Department of Languages and Literatures

University of Ottawa

Ottawa, ON

K1N 6N5

Distinguished University Professor

Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada

The Chronicles of Spirit Wrestlers' Immigration to Canada

God is not in Might, but in Truth

I am happy to announce that this life long project has come to an end; the translation into English of this basic record of our Doukhobor movement from the early life in the Caucasus in Russia to Peter V. Verigin's death in Canada.

The book begins with the childhood of Peter Verigin and portrays the author’s loving memories of Lukeria Kalmykova. It contains not only the important episodes of the Burning of the Weapons, brutal punishments in Russian prisons and subsequent exile to the most isolated locations in Siberia, a perilous escape to Canada and misunderstandings and discrimination by the Canadian government, but also some fundamental Doukhobor beliefs, such as pacifism, equality, communion with God without churches or icons, vegetarianism, and agrarianism.

It also explains early conflicts with the government, why many Doukhobors did not swear allegiance to the British monarch, as well as refusal by many to send children to English schools.

Written over the years by Peter's younger brother Grisha, this account had first hand input from all contemporaries as he worked on it over the years, and was first published in Russian in Paris through the efforts of Pavel Birukov, long time friend of the Doukhobors and Tolstoy biographer.

It has long been an ambition of mine to see this narrative published in English, as in my life time, the Russian language became more elusive in our society and not generally read by Canadian historians and scholars. Another reason for wanting publication was the fact that my great grandfather was Vasili, Peter Verigin's older brother, and as the book reveals, a key player as courier of important messages such as the Arms Burning, and also visiting Tolstoy in Moscow. One of our revered ancestors, who continued to play an important role in the Canadian settlement as well.

My early efforts at translating some select parts had much assistance and encouragement from many friends and colleagues, most notably William Popove, primary Doukhobor civil engineer and noteworthy surveyor, my aunt Pauline Vishloff, UBC Professor Jack MacIntosh and my former wife Dr. Galina Alekseeva. I am also grateful to the Secretary of State Multiculturalism Department for a modest grant to assist my efforts. Along the way, my immediate family, as always, was supportive and inspirational.

The key to the success of this project was Professor Veronika Makarova. We had met on some other mutual Doukhobor projects and through much discussion, we soon settled on bringing this worthwhile narrative to an English speaking audience.

Beginning with the title page, we worked on the translation of this work for the last seven years. I am eternally grateful for her diligence, knowledge and meticulous skill as an inquiring translator and her penetrating insight into some obscure passages which in the end, came to an intelligent expression. Over these years, we were in contact almost daily, exploring the final minutiae of nuance and detail.

It was through her diligence and academic credentials that a notable publisher was located and together, we proof read the final version several times.

It was a long journey resulting in a successful conclusion to this endeavour, but thanks to her dedication, this chapter of our activity has come to a triumphant conclusion. We will now be able to seek other challenges.

The book is available at: www.doukhoborstore.com/books.html

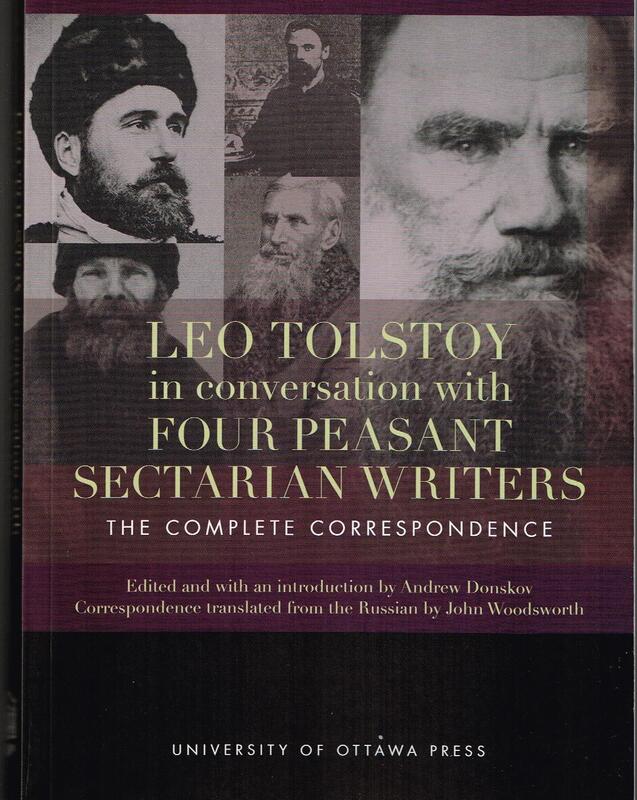

LEO TOLSTOY

in Conversation with

FOUR PEASANT SECTARIAN WRITERS

EDITED BY Andrew Donskov

Letters compiled by Liudmila Gladkova

Correspondence translated from the Russian by John Wordsworth

UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA PRESS 2019

This talented team, all experts in their domains, have produced another worthwhile tome for the benefit of Tolstoy scholars. Most readers of Tolstoy note his natural sympathy for the powerless and voiceless, but in this case, thanks to his own influence and reputation, he assists these sincere believers in giving them a voice, a voice they possibly would not have on the open market. Along with friend and colleague, Vladimir Chertkov, he was in charge of Posrednik, their publishing house which concentrated on religious philosophical enlightenment, and also had connections with other publishers.

Such was the case with T. M. Bondarov, who appears to live in respectful awe of the literary master and begs for his assistance.

On the other hand, correspondence with Peter V. Verigin is more casual and social and a sharing of concepts and quandaries.

The letters are prefaced by a lucid introduction by Andrew Donskov, F. R' S. C., Distinguished University Professor, about Tolstoy and his stance on peasant sectarians.

In addition, the book contains a Bibliography, a list of Tolstoy titles, and an index of names.

Four major correspondents are featured: T. M. Bondarev, Subbotnik, F. Zheltov, Molokan, P. V. Verigin, Doukhobor, and M. P. Novikov.

All of these dissidents were in awe of Tolstoy as their mentor and leader. However, Tolstoy was equally appreciative of such spokespersons, who chose to deviate from the Orthodox Church, and form a bond with the rural peasantry which was being abused by all authority including the Church.

These writers as well as Tolstoy, saw a profound dignity in the peasant non-class, and felt that they deserved the dignity and the proper, respectful place in the foundation of the society of the time.

This is the frame work in which the correspondence takes place, and all ideas and nuances are explored from different angles by these four major peasant writers.

This book is an essential part of any library connected to the Tolstoy philosophical theories and writings. Any serious scholar would enjoy the wealth of information in this collection.

in Conversation with

FOUR PEASANT SECTARIAN WRITERS

EDITED BY Andrew Donskov

Letters compiled by Liudmila Gladkova

Correspondence translated from the Russian by John Wordsworth

UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA PRESS 2019

This talented team, all experts in their domains, have produced another worthwhile tome for the benefit of Tolstoy scholars. Most readers of Tolstoy note his natural sympathy for the powerless and voiceless, but in this case, thanks to his own influence and reputation, he assists these sincere believers in giving them a voice, a voice they possibly would not have on the open market. Along with friend and colleague, Vladimir Chertkov, he was in charge of Posrednik, their publishing house which concentrated on religious philosophical enlightenment, and also had connections with other publishers.

Such was the case with T. M. Bondarov, who appears to live in respectful awe of the literary master and begs for his assistance.

On the other hand, correspondence with Peter V. Verigin is more casual and social and a sharing of concepts and quandaries.

The letters are prefaced by a lucid introduction by Andrew Donskov, F. R' S. C., Distinguished University Professor, about Tolstoy and his stance on peasant sectarians.

In addition, the book contains a Bibliography, a list of Tolstoy titles, and an index of names.

Four major correspondents are featured: T. M. Bondarev, Subbotnik, F. Zheltov, Molokan, P. V. Verigin, Doukhobor, and M. P. Novikov.

All of these dissidents were in awe of Tolstoy as their mentor and leader. However, Tolstoy was equally appreciative of such spokespersons, who chose to deviate from the Orthodox Church, and form a bond with the rural peasantry which was being abused by all authority including the Church.

These writers as well as Tolstoy, saw a profound dignity in the peasant non-class, and felt that they deserved the dignity and the proper, respectful place in the foundation of the society of the time.

This is the frame work in which the correspondence takes place, and all ideas and nuances are explored from different angles by these four major peasant writers.

This book is an essential part of any library connected to the Tolstoy philosophical theories and writings. Any serious scholar would enjoy the wealth of information in this collection.

HISTORICAL SAGA OF THE DOUKHOBOR FAITH 1750 - 1990s

by Sam George Stupnikoff

Printed by Apex Graphics, Saskatoon, 1992

85 p. $9.00 sc

This book is on sale and has been making its way into some library collections as an addition to their growing archival sources on the Doukhobors. Given that, correction procedure is in order.

While one must laud another positive book about the Doukhobors, particularly in view of the high profile anniversaries of the immigration and Arms Burning in 1995, Mr. Stupnikoff, a self styled publisher and historian, has made several serious errors in this modest epistle. Loose structure and style aside, I believe it is important to point out these significant errors.

On page 13, Mr. Stupnikoff states: 'An appeal was made to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, by the Society of Friends to grant refuge for the Doukhobors in their new country where they could have their religious freedom and permanent settlement. Her Majesty responded to this appeal and granted refuge, permitting the Doukhobors to migrate to Canada with full religious privileges including exemption from military service.'

An example of a 'modern myth' which grew up among the Doukhobors from uncertain origins, and one which should be appropriately laid to rest.

In fact, no such appeal was ever made; the emigration of the Doukhobors was a much more complex matter: Is it possible that Mr. Stupnikoff is referring to an appeal made by the English Society of Friends in London directly to the Tsar in 1897?

In a recent letter from Miss Allison Derrett, Assistant Registrar of the Royal Archives of Windsor Castle, Berkshire, Miss Derret writes: ' . . . I fear that . . . this is going to be a very disappointing reply, since I was unable to find any reference to the Doukhobors in any of the relevant indexes . . . This confirms . . . that the emigration was largely due to the efforts of Leo Tolstoy and the Society of Friends, and does not suggest any Royal or Government involvement. . . . I am sorry we are unable to help, but I am afraid we have no information here on the Doukhobors.'

Aside from a reference in the Encyclopedia Britannica, there is no mention of the word 'Doukhobor' in the entire Royal Archives, so it is not possible that Queen Victoria had ever even heard the word.

In a further letter from the Public Record Office, Surrey, I was told that: 'In regard to the initial contact between the Doukhobors and the British Government being made Batoum, I indicated in my previous letter that I inferred this from a coded telegram, and its accompanying minute, sent by the Governor General of Canada to the Colonial Office in October 1898 (CO 42/858 ff 726-727). Since then I have looked at some material in the record class FO 65 (General Correspondence before 1906 Russia), which confirms this. In particular, I draw your attention to piece FO 65/1564, which contains a communication in cipher written by Consul Stevens at Batoum in July 1898, and which reveals that a delegation of Doukhobors applied to him seeking the British Government's approval to plans for their emigration to Cyprus (FO 65/1564 ff 146-7). It is highly probable that the same approach was made in relation to their emigration to Canada.'

This letter came from James Murray, of the Search Department of the Public Records Office, Surrey, The Government of England. My entire research archive into the Doukhobor immigration has been donated to the University of Calgary and is available for viewing.

The Doukhobor delegation named above consisted of Ivan Ivin and Peter Makhortoff, aided by Prince Hilkov. They had travelled to England, then to Cyprus, then back to England; then on to Canada, by this time joined by their families and Aylmer Maude, forming a total party of ten. During their time in Canada, they toured the potential site of settlement (free passage arranged by Maude).

While Hilkhov and the two Doukhobor families examined the land, Maude and James Mavor had two meetings with James Smart, Deputy Minister of the Interior. The final decision to admit the Doukhobors to Canada as colonists was made in a meeting with Maude and Smart on October 5th., and in a further meeting between James Mavor and Clifford Sifton on October 28, 1897. At this time, the three locations of settlement were also decided upon.

Needless to say, Queen Victoria, by this time a frail and feeble 78 years old, and occupied with the South African campaign (to what little extent she could be occupied with anything, she died three years later) was not aware of any dealings of the Canadian negotiations or even of the word 'Doukhobor'.

As for the exemption from military service, the Militia Act had existed in Canada since 1868, and read: 'Every person bearing a certificate from the Society of Quakers, Mennonites or Tunkers, or any inhabitant of Canada, of any religious denomination, otherwise subject to military duty, but who, from the doctrine of religion, is averse to bearing arms and refuses personal military service, shall be exempt from such service when balloted in time of peace, or war, upon such conditions and under such regulations as the Governor in Council, may, from time to time, prescribe.'

When all other arrangements were complete, the government, through an Order-in-Council, specifically named the Doukhobors for inclusion in the Militia Act on December 6, 1898.

Military exemption for the Doukhobors became a fact from that day forward, and of course, once again, Queen Victoria had nothing to do with it.

On page 17, the author says that Leo Tolstoy received the Nobel Prize for Literature for writing the novel: Resurrection.

In fact, the author of WAR AND PEACE, perhaps the greatest novel of all time, never received the Nobel Prize.

When he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1897 he wrote to the Stockholm newspaper renouncing his nomination, and suggested that the Doukhobors should be nominated instead.

On the same page, the author says that the first ship of immigrants was under the care of Sergius Tolstoy - this too, is incorrect; the first ship was under the care and supervision of Leopold Sulterzhitsky, who later wrote a famous book about his experience: TO AMERICA WITH THE DOUKHOBORS. (Sergius Tolstoy supervised the second ship, the Lake Superior.)

On page 25, across from a picture of women pulling a plow, we read the statement that: 'Action of this nature by Doukhobor women occurred only in one instance.' Far from that, some estimates suggest that this occurred in nearly every village, and that up to 100 acres per village was plowed in this fashion. This appears credible, since no one village was more destitute than any other, men were away in all cases, and if gardens were to be grown, sod had to be broken. Also, there are reports of this happening in more than one year, (1899 and 1900), with numbers of the plowing teams ranging from 14 to 24 women. Furthermore, there is more than one photograph of such plowing. (While most Doukhobors consider this an event unique to Doukhobor settlement, it should be noted that this form of tilling took place among other pioneer folk in North America as well.)

Peter Verigin did not meet with Aylmer Maude in England. By this time Maude had found other interests; however, a meeting did take place with Vladimir Tchertkov, head of the immigration committee.

There is a famous photograph of this meeting, and I had in my possession a rare photograph of Peter Verigin not only with Tchertkov but also with Tchertkov's son, Dmitri, now donated to the Doukhobor Discovery Centre.

Mr. Stupnikoff goes on to make various minor errors (i.e. there are no Doukhobors in Taber, Alberta; he probably means Shouldice, the settlement of Anastasia Lords. The communal centre in the Doukhobor villages was never known as a PRAYER HOME, but simply as the 'HOME'; DOM in Russian, a central building which served variously as a centre for social interaction ranging from business meetings to official receptions; on Sundays, prayer meetings were held there; the appropriate translation would be: COMMUNITY CENTRE.)

However, the greatest errors, aside from the emigration facts, are in reference to the Verigin family.

On page 51, we are told that Verigin's wife, Anastasia, died soon after he settled in Canada in 1927. When Verigin died in 1939, his wife (Anna, not Anastasia) in fact, was sobbing nearby.

Further errors follow: We are told that Peter P. Chistakov had made arrangements for his eighteen year old grandson to immigrate to Canada in 1928, and that he assumed the name of Verigin. In Russia, as in Canada, it is quite in order for adopted children to appropriate the names of their adoptive parents.

John Verigin's father, Ivan Voykin, died one month before John J. was born and the infant was brought up in his grandfather's house; henceforth to be known as Verigin. When he came to Canada with his grandmother, Anna, he was six years old, not eighteen. When Chistakov came to Canada, he had been working with the Russian Doukhobors, and at that time, was supervising the construction of a cheese factory. Therefore, he did not 'leave' to 'join the Doukhobors', but had spent all of his life among them. Whether or not he 'favoured individual ownership' is certainly a matter for discussion. He came to Canada to guide his father's commune, and did his utmost to preserve the CCUB against the onslaught of the depression and the trust companies.

Finally, John J. Verigin, was acclaimed Honorary Chairman on July 22 and 23, 1961, and not August 16, 1960, as stated. Given this multitude of errors in a mere 85 pages, it is hard to comment on other aspects of a book such as layout, typography, organization and general readability. A book such as this is generally purchased for the information it contains rather than light reading - therefore it must be viewed and judged with that in mind.

There have been many such 'sagas' written and available to the general public. Some of them, no doubt, will find their way into the educational system.

Bearing this in mind, perhaps this is the time to sweep aside the 'sagas' (legends) and take this opportunity to begin presenting the facts of this important historic occasion as they happened; rather than as how they may have been passed down through a misty, fuzzy, foggy recollection of myths, sagas, and hoary tales of legerdemain. All of the facts are available, we are dealing here with recent history. Why not avail ourselves of the readily obtainable truth?

Better yet, why not pass this truth on to future generations, so the events of this important historical event will be available for the coming generations of Doukhobor children and the public at large?

The immigration of the Doukhobors is one of the outstanding and unique events of this century. The facts do not need embellishments or any fanciful notions beyond the events as they happened. In this case, truth could well be stranger than fiction, perhaps even more interesting - why not give it a try?

PRINCE PETER KROPOTKIN

1824 - 1921

In Russian and French Prisons

by Peter Kropotkin

Introduction by George Woodcock

Much Rose Books, Montreal/New York, 1991 Edition

387 p. $38.95 hc, $19.95 sc

Introduction: Peter Kropotkin, 1842-1921, was a foremost geographer of his day but, along the way, came to be regarded as a humanist because of his espousal of some unpopular causes. Because he renounced his title (Prince), and took up the cause of the peasants, he was declared an anarchist and soon found himself in a series of Russian prisons. Kropotkin had travelled through Western Canada in 1897 and was impressed by the Mennonite settlements, people living communally with seemingly little interference from the authorities. While visiting James Mavor, Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, a letter arrived from Leo Tolstoy, explaining the plight of the Doukhobors and their need for a refuge. His suggestion was that these best farmers in Russian, according to Tolstoy, would do well in the mid-west. Mavor then wrote to Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior, who was conducting an aggressive campaign to settle the west. He felt that these would be perfect immigrants for settling the virgin prairies.

This communication eventually resulted in the invitation to the Doukhobors to settle on special land grants provided by the Dominion government. The following is a review of one of his most famous books: In Russian and French Prisons. This book can be downloaded or read on the following site: http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/kropotkin/prisons/toc.html

Peter Kropotkin, 1842-1921, was a foremost geographer of his day but, along the way, came to be regarded as a humanist because of his espousal of some unpopular causes.

After a daring escape from Siberia he served a three-year stretch in the French penal system. After that, he carried on his work and world travels from the relative safety of a base in England. George Woodcock, since deceased, and himself known as a 'gentle' anarchist - "No matter who you vote for, the government always gets in" - offers a relatively benign preface to this dreary journey which quickly plunges us into the depths of the horrific lives of the incarcerated from the so-called 'normal' fortress prisons in Russia, through Siberia, all the way to the awesome desperation of Sakhalin Island, to the relative luxury and civilized aspects of the French experience.

Mr Kropotkin is an apt guide for this Stephen King type of inspired nightmare as we scan the extent of human depravity and man's inhumanity to man. Not only has he had the personal experience of these prisons, he has read all reports on the subject and also associated with various former convicts from different prisons.

Compared to our present system, with all of its inadequacies, this visit to the incarcerated life of the 1880s reads like a gothic hallucination. Each page discloses an even more profound horror and while we know that thousands died under this regime, what challenges the imagination is that, somehow, some survived, not just for years but for decades.

I will provide some glimpses by way of illustration. Any convict could be punished by five to six thousand strokes of the whip, this an improved modification in 1857, replacing the knut and branding iron. Those sentenced to hard labour in Siberia faced a march of roughly five thousand miles, taking between two and three years. This walk would he performed with chains riveted to the ankles, proceeding up each leg and attached to an iron girdle. Other chains bound both hands, a third binds six to eight convicts together.

Wives and children, not guilty of any crimes but wanting to be with their menfolk, formed the rear of this mass movement, whipped and beaten by guards to make them keep up. Their naked, emaciated bodies and wounded feet appeared through their rags. There was 'little food and no new clothes. No less than a thousand convicts died in the course of one summer's walk'.

In those days before the borrowing of mass sums of money on slips of paper, the Royal Treasury needed gold arid silver. When the prisoners reached their goal they were rented out to private overseers in these mines. Some were designated to the salt mines, a shorter sentence since few survived for long at that occupation.

As the ore diminished, more and more convicts were forced to work harder, more died and so on - an inevitable result similar to more sophisticated ships hunting fewer whales. Torture was not uncommon. The guards were extortionist beasts, pure and simple: an honest guard was soon recalled or killed. In one case, an eleven-year-old girl was hung upside down and flogged from the soles or her feet to her head. Crying for water, she was given a salted herring.

Native hunters made a living shooting the escapees: 'An antelope gives but one skin, while the chaldon gives at least two, his shirt and his coat.' Then there was the bounty of five roubles, ten if the escapee was still alive.

The life of barbarities destroys all compassion and the human mind soon disintegrates into the basest animistic instincts. The guards, prisoners in their own way, lose their minds in a parallel fashion to the convict; they would not survive if they retained 'normal' feelings.

Here one could be riveted to a barrow for six years or attached to a forty-eight pound piece of metal or log for several years. (This prevented rapid movement for escape and also made forced labour difficult.)

In the fortress prisons people disappeared into secret cells for years with no outside communication. One inmate managed to smuggle out a letter written in his own blood with a nail, just to inform people he was there.

The celebrated poet Pushkin, emerged from prison after fifteen years as though he had disappeared. He had never seen a judge, his wife was allowed to see him only after fourteen years. In one year 70,000 people from a list of 200,000 vanished without record or trace.

What were the crimes to merit such punishment? Murder, burglary, forgery will all bring a man to hard labour, so will a suicide attempt, so will sacrilege and blasphemy, any disobedience of the authorities which was defined as rebellion and vagrancy, which might mean an escapee.

One lady was found guilty of starting a school for peasants. Political offenders meant anyone who belonged to a suspect society, even writers of 'dangerous romances'. Other criminals were religious dissenters, those of 'turbulent' character, strikers, and those accused of 'verbal offences' against the Sacred Person of His Majesty, the Emperor. In 1831. 2500 people were arrested for this offence within a six month period.

Others were exiled to Siberia BECAUSE it was impossible to commit them to trial, there being no 'proofs' against them. Children were included without any special consideration: "I shall never forget the children I met one day in the Garrison of the House or Detention. They also, like us, were awaiting trial for months and years. Their greyish, yellow emaciated faces, their frightened and bewildered looks were worth whole volumes of essays and reports on 'the benefits of cellular confinement in a model prison'.

Some prisoners would have to live over a hundred years to complete their sentences (an anachronism in sentencing that still exists). But, in these prisons, time was not the enemy. Starvation, scurvy, mercury emanations in the mines, dissipation and exhaustion caused by lack of food, totally uncontrolled climate, scourgings, and the gradual creeping insanity and madness as the mind rotted in the body from hour to hour made time immaterial.

The cell was a grave, the silent padding of a guard a hunter stalking his prey, the groans of the wretched a premonition of what was to come.

After his heroic escape from this dismal servitude, what conclusions does Peter make? 'The principle of LEX TALIONIS - of the right of the community to avenge itself on the criminal is no longer admissible. We have come to an understanding that society at large is responsible for the vices that grow in it, as well as its share of heroes. Reform must begin with the rebuilding of all prisons (not a new coat of whitewash), changing the laws, replacing the staff from the first to the last man. One recommendation is to sell tobacco in order to halt its ferocious illicit trade and to cut down on its use. (Tobacco was so coveted that each pinch was first chewed, then dried and smoked, then the ashes sniffed.)

Then, as now, the rule of society seemed to be that it was okay to steal, as long as you didn't get caught; therefore the lessons learned on the outside were no better than those on the inside. A common prison quote was: 'The real thieves, sir, are those who keep us in here - not those who are in'.

In a prisoner's greyish life, 'which flows, without passions or emotions, all those best feelings which may improve human character soon die away.' To prevent this; prisoners should be allowed to exercise, to work (outside of Siberia the rule was enforced idleness), to read books and to write letters.

The years of barbaric solitary confinement should be abolished. (P. K. had served two-and-one-half years in strict solitary.) Graduates of prisons became less and less adapted for life in society therefore PREVENTION (as in medicine) - is the best cure - CRIME IS A SOCIAL DISEASE.

'This illness ought to be submitted to some treatment instead of being aggravated by imprisonment'. In support of this is the observation that capital punishment had been abolished in 1753; murderers served a basic twenty years in Siberia. After that; they settled for a free life in the same territory. This area is full of liberated assassins, yet it is the safest place to travel and find hospitality with few criminal offences. Yet, in areas such as Tomsk and Western Siberia, where minor offenders settled, murderous crimes are rampant! ('The practice of putting men to death was the result of craven fear, coupled with remnants of a lower degree of civilization when a tooth-for-tooth principle was preached by religion'.)

In the end, Peter K. reiterates the concept that the old custom by which each commune (clan, Mark Gemeinde) was considered responsible as a whole for any anti-social act committed by any of its neighbours. This would result in crimes being recognized and addressed rather than hidden and punished.

Children who knew no feature of home or human kindness but were exposed and subjected to every vice would have an opportunity to enter the mainstream as contributors rather than as problems. It is worthwhile to note that the indigenous people of North America are attempting to reintroduce the concept of the healing circle into their own tribes (if our justice system will allow them to).

Although parts of this book began to appear in 1882 much of it is timely today - we have changed some physical structures but we have not progressed beyond the philosophical concepts of that time in one's views towards offenders. Consequently, the problem is still with us, particularly in Canada which has one of the highest incarceration (and recidivism) rates in the world.

If one can read this book without being dulled by sensory overload, there is much to he learned by sharing Kropotkin's experiences and insights. However, concentrating on and confronting these same experiences can also be a depressing experience.

by Peter Kropotkin

Introduction by George Woodcock

Much Rose Books, Montreal/New York, 1991 Edition

387 p. $38.95 hc, $19.95 sc

Introduction: Peter Kropotkin, 1842-1921, was a foremost geographer of his day but, along the way, came to be regarded as a humanist because of his espousal of some unpopular causes. Because he renounced his title (Prince), and took up the cause of the peasants, he was declared an anarchist and soon found himself in a series of Russian prisons. Kropotkin had travelled through Western Canada in 1897 and was impressed by the Mennonite settlements, people living communally with seemingly little interference from the authorities. While visiting James Mavor, Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, a letter arrived from Leo Tolstoy, explaining the plight of the Doukhobors and their need for a refuge. His suggestion was that these best farmers in Russian, according to Tolstoy, would do well in the mid-west. Mavor then wrote to Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior, who was conducting an aggressive campaign to settle the west. He felt that these would be perfect immigrants for settling the virgin prairies.

This communication eventually resulted in the invitation to the Doukhobors to settle on special land grants provided by the Dominion government. The following is a review of one of his most famous books: In Russian and French Prisons. This book can be downloaded or read on the following site: http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/kropotkin/prisons/toc.html

Peter Kropotkin, 1842-1921, was a foremost geographer of his day but, along the way, came to be regarded as a humanist because of his espousal of some unpopular causes.

After a daring escape from Siberia he served a three-year stretch in the French penal system. After that, he carried on his work and world travels from the relative safety of a base in England. George Woodcock, since deceased, and himself known as a 'gentle' anarchist - "No matter who you vote for, the government always gets in" - offers a relatively benign preface to this dreary journey which quickly plunges us into the depths of the horrific lives of the incarcerated from the so-called 'normal' fortress prisons in Russia, through Siberia, all the way to the awesome desperation of Sakhalin Island, to the relative luxury and civilized aspects of the French experience.

Mr Kropotkin is an apt guide for this Stephen King type of inspired nightmare as we scan the extent of human depravity and man's inhumanity to man. Not only has he had the personal experience of these prisons, he has read all reports on the subject and also associated with various former convicts from different prisons.

Compared to our present system, with all of its inadequacies, this visit to the incarcerated life of the 1880s reads like a gothic hallucination. Each page discloses an even more profound horror and while we know that thousands died under this regime, what challenges the imagination is that, somehow, some survived, not just for years but for decades.

I will provide some glimpses by way of illustration. Any convict could be punished by five to six thousand strokes of the whip, this an improved modification in 1857, replacing the knut and branding iron. Those sentenced to hard labour in Siberia faced a march of roughly five thousand miles, taking between two and three years. This walk would he performed with chains riveted to the ankles, proceeding up each leg and attached to an iron girdle. Other chains bound both hands, a third binds six to eight convicts together.

Wives and children, not guilty of any crimes but wanting to be with their menfolk, formed the rear of this mass movement, whipped and beaten by guards to make them keep up. Their naked, emaciated bodies and wounded feet appeared through their rags. There was 'little food and no new clothes. No less than a thousand convicts died in the course of one summer's walk'.

In those days before the borrowing of mass sums of money on slips of paper, the Royal Treasury needed gold arid silver. When the prisoners reached their goal they were rented out to private overseers in these mines. Some were designated to the salt mines, a shorter sentence since few survived for long at that occupation.

As the ore diminished, more and more convicts were forced to work harder, more died and so on - an inevitable result similar to more sophisticated ships hunting fewer whales. Torture was not uncommon. The guards were extortionist beasts, pure and simple: an honest guard was soon recalled or killed. In one case, an eleven-year-old girl was hung upside down and flogged from the soles or her feet to her head. Crying for water, she was given a salted herring.

Native hunters made a living shooting the escapees: 'An antelope gives but one skin, while the chaldon gives at least two, his shirt and his coat.' Then there was the bounty of five roubles, ten if the escapee was still alive.

The life of barbarities destroys all compassion and the human mind soon disintegrates into the basest animistic instincts. The guards, prisoners in their own way, lose their minds in a parallel fashion to the convict; they would not survive if they retained 'normal' feelings.

Here one could be riveted to a barrow for six years or attached to a forty-eight pound piece of metal or log for several years. (This prevented rapid movement for escape and also made forced labour difficult.)

In the fortress prisons people disappeared into secret cells for years with no outside communication. One inmate managed to smuggle out a letter written in his own blood with a nail, just to inform people he was there.

The celebrated poet Pushkin, emerged from prison after fifteen years as though he had disappeared. He had never seen a judge, his wife was allowed to see him only after fourteen years. In one year 70,000 people from a list of 200,000 vanished without record or trace.

What were the crimes to merit such punishment? Murder, burglary, forgery will all bring a man to hard labour, so will a suicide attempt, so will sacrilege and blasphemy, any disobedience of the authorities which was defined as rebellion and vagrancy, which might mean an escapee.

One lady was found guilty of starting a school for peasants. Political offenders meant anyone who belonged to a suspect society, even writers of 'dangerous romances'. Other criminals were religious dissenters, those of 'turbulent' character, strikers, and those accused of 'verbal offences' against the Sacred Person of His Majesty, the Emperor. In 1831. 2500 people were arrested for this offence within a six month period.

Others were exiled to Siberia BECAUSE it was impossible to commit them to trial, there being no 'proofs' against them. Children were included without any special consideration: "I shall never forget the children I met one day in the Garrison of the House or Detention. They also, like us, were awaiting trial for months and years. Their greyish, yellow emaciated faces, their frightened and bewildered looks were worth whole volumes of essays and reports on 'the benefits of cellular confinement in a model prison'.

Some prisoners would have to live over a hundred years to complete their sentences (an anachronism in sentencing that still exists). But, in these prisons, time was not the enemy. Starvation, scurvy, mercury emanations in the mines, dissipation and exhaustion caused by lack of food, totally uncontrolled climate, scourgings, and the gradual creeping insanity and madness as the mind rotted in the body from hour to hour made time immaterial.

The cell was a grave, the silent padding of a guard a hunter stalking his prey, the groans of the wretched a premonition of what was to come.

After his heroic escape from this dismal servitude, what conclusions does Peter make? 'The principle of LEX TALIONIS - of the right of the community to avenge itself on the criminal is no longer admissible. We have come to an understanding that society at large is responsible for the vices that grow in it, as well as its share of heroes. Reform must begin with the rebuilding of all prisons (not a new coat of whitewash), changing the laws, replacing the staff from the first to the last man. One recommendation is to sell tobacco in order to halt its ferocious illicit trade and to cut down on its use. (Tobacco was so coveted that each pinch was first chewed, then dried and smoked, then the ashes sniffed.)

Then, as now, the rule of society seemed to be that it was okay to steal, as long as you didn't get caught; therefore the lessons learned on the outside were no better than those on the inside. A common prison quote was: 'The real thieves, sir, are those who keep us in here - not those who are in'.

In a prisoner's greyish life, 'which flows, without passions or emotions, all those best feelings which may improve human character soon die away.' To prevent this; prisoners should be allowed to exercise, to work (outside of Siberia the rule was enforced idleness), to read books and to write letters.

The years of barbaric solitary confinement should be abolished. (P. K. had served two-and-one-half years in strict solitary.) Graduates of prisons became less and less adapted for life in society therefore PREVENTION (as in medicine) - is the best cure - CRIME IS A SOCIAL DISEASE.

'This illness ought to be submitted to some treatment instead of being aggravated by imprisonment'. In support of this is the observation that capital punishment had been abolished in 1753; murderers served a basic twenty years in Siberia. After that; they settled for a free life in the same territory. This area is full of liberated assassins, yet it is the safest place to travel and find hospitality with few criminal offences. Yet, in areas such as Tomsk and Western Siberia, where minor offenders settled, murderous crimes are rampant! ('The practice of putting men to death was the result of craven fear, coupled with remnants of a lower degree of civilization when a tooth-for-tooth principle was preached by religion'.)

In the end, Peter K. reiterates the concept that the old custom by which each commune (clan, Mark Gemeinde) was considered responsible as a whole for any anti-social act committed by any of its neighbours. This would result in crimes being recognized and addressed rather than hidden and punished.

Children who knew no feature of home or human kindness but were exposed and subjected to every vice would have an opportunity to enter the mainstream as contributors rather than as problems. It is worthwhile to note that the indigenous people of North America are attempting to reintroduce the concept of the healing circle into their own tribes (if our justice system will allow them to).

Although parts of this book began to appear in 1882 much of it is timely today - we have changed some physical structures but we have not progressed beyond the philosophical concepts of that time in one's views towards offenders. Consequently, the problem is still with us, particularly in Canada which has one of the highest incarceration (and recidivism) rates in the world.

If one can read this book without being dulled by sensory overload, there is much to he learned by sharing Kropotkin's experiences and insights. However, concentrating on and confronting these same experiences can also be a depressing experience.

The Doukhobor People

A Tribute to Good Citizens

Ken Morrow

Recently, a professor friend of mine asked for my opinion on a book he was reading. I recalled that I thought it was quite flawed. Could I be more specific? I was going away on a week’s retreat, so I said I would try to locate the book and find some specific examples. Then, I began to write a review:

Dr. Morrow [optometry] cites a substantial bibliography at the end of this slim volume [142 p.] as well as no less than thirteen personages in his ‘Acknowledgments’. With that in mind, I concluded that he should have made some use of these sources. I also wondered why some of his historical consultants did not review the manuscript before it was published with their congratulatory remarks?

Let’s check out the images first:

P. 69: Peter V. Verigin was born July 28, not July 12 as reported here.

P. 71: The date cited is incorrect. The explosion that killed Peter V. Verigin occurred on October 29, 1924, not October 28, as stated. The photo does not look like a damaged railway car.

[See: www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/verigin/explosion/3d/3158en.html]

P. 72: This photo shows the burial image of Peter P. Verigin in 1939, not Peter V. Verigin in 1924.

P. 87: Doukhobors building a road . . . The caption is simplistic. One of the features of the Russian commune mir system was a broad thoroughfare between two rows of houses. Here communal animals such as chickens and cows could be corralled and herded, assemblies could be held, as well as fenced off protected areas for gardens maintained. There was little demand for roads as there was little traffic as we know it. It is also worth noting that for the most part, as can be discerned in the image, this work was done by women, children and elders while capable menfolk worked for wages to buy seed and implements for farming.

P. 89: Some thatching was done by Doukhobor settlers, but this was more prevalent among independent Ukrainian folk. A more appropriate early dwelling would be the zemlanka, emergency dwellings made by digging out shelters from hill sides.

[See: www.doukhobordugouthouse.com/ ].

P. 90: A well known image but misleading caption: The women, plowing sod in order to plant gardens, were not plowing because of a shortage of horses. There were no horses for this work, and the energetic women, realizing that they would be facing starvation without gardens, took it upon themselves to break the virgin sod.

P. 92: I have serious doubts about the accuracy of this picture. As far as I know, the Doukhobors in B. C. did not wear the military style caps, they were gone by then. This could be early Saskatchewan or even Russia.

P. 93: The date of this photograph is not correct. It is most likely c. 1927, showing Peter P. Verigin with his wife and mother and John J. Verigin Sr, his adopted son, when he arrived in Canada.

THE TEXT:

Mr. Morrow begins his rambling recollection by stating: the Greek Orthodox Church on P. ix. This should be Russian Orthodox Church.

On P. 2 Mr Morrow states that: ‘Inaccurate and misleading recorded and spoken historical information continues to negatively affect these God fearing, hard working people today’. However, as the reporter ‘on the ground', he does not cite any of this written or spoken information, but rather goes on to present more inaccuracies.

[See: http://www.larrysdesk.com/doukhobors-and-the-media.html].

He recalls some Doukhobor friends he had in school. It appears that he accepts Doukhobors as friends because they seem to be almost like him. He does little to discover their beliefs or culture, and on P. 7, he treats his Doukhobor friend to a hamburger, someone who most likely was a vegetarian, existing, as he says, on ‘cans of soup or spaghetti’. Should he have considered this diet further before his ‘treat’?

Earlier, on P. 5, he says: ‘During my five years of high school I knew of only one Doukhobor boy who had a date with a non-Doukhobor girl’. Presumably, he himself continued this segregation, although on P. 4 he quotes his friend who speaks knowingly about a girl who ‘gives me and my friends sex. Why can’t you?’; this to Mary Voykin, who refused to give them sex. Presumably she was not ‘dating’ material.

Throughout the book he continually refers to the Doukhobors’ lack of education and poor use of English. Growing up in Alberta, we were taught that an accent usually indicated that the speaker knew another language, and it was not a cause for derision. In Mr. Morrow’s ‘British’ Columbia, it appears to be a serious handicap. In most immigrant communities, little would be made of this. [See: As The Crow Flew, compiled by Larry Ewashen, in which thirty-five separate nationalities lived harmoniously side by side and celebrated this by having an inter group annual banquet where all of the various groups contributed ethnic food].

[See: http://www.doukhoborstore.ca/html/books.htm]

While decrying the lack of compassion and understanding of the Doukhobor immigrants by himself and others, he describes how he joined the hilarious abuse of this group by locking an ‘illiterate ignorant’ Doukhobor gardener in his grandmother’s outhouse. [P. 10]

P. 15 - 16, he presents a mistaken view of the Doukhobor concept of God. While this particular Doukhobor may have believed in a manipulative, dictatorial God, this is not part of the belief system, although the concept of the ‘God within’ is. To compound his lack of compassion and sensitivity, he reports this incident with a smug superiority, prefacing his report with: ‘He exclaimed in a very loud broken English in a high pitched voice that could be heard all over the bus’. Oh horrors, Dr. Morrow possibly observed talking to a Doukhobor!

Perhaps Mr. Morrow should have investigated further, as in this case his report is totally superficial, similar to an earlier reference to a funeral where the Doukhobors essentially sat at tables and ate all afternoon. [The Doukhobor funeral is replete with specific rites and it is apparent that he has missed this completely].

This is the consistent superficial tone throughout, so aside from trumpeting his own superiority, I really wonder why he bothered to write this shallow portrayal? The Doukhobors only needed to be normal people as they were, it was Mr. Morrow and his fellow citizens who appear to be suffering from an innate inability to treat people with equality and respect. No doubt this is an impression that Mr. Morrow did not intend to convey, but this becomes evident as one proceeds through this dreary diatribe.

He then goes on to describe how a Doukhobor neighbour poisoned his dog, Bertie, although no proof aside from general gossip is offered. Herein, also lies the basic racist tone of the tome: If I suspected my neighbour of taking a saw to my dog [as Jimmy Carter did when the dog ate his cat’s food], would I say, my neighbour, the Rosicrucian, attacked my dog, or would I say, my neighbour attacked my dog? What is the Rosicrucian reflection on the matter, are we to surmise that all Rosicrucians are attackers of dogs or all Doukhobors [likely] poison dogs?

Along the way he condemns the anarchistic protests of the Sons of Freedom, without any research into the grievances that stimulated such actions.

[See: www.larrysdesk.com/hope-history-conference-bridging-the-past.html ]

He then mentions a man from the east who married a Doukhobor woman because he he did not know who the Doukhobors were, Doukhobors who condemned the Sons of Freedom and Doukhobors who joined the Protestant church.

All this and I am only to page nineteen, and all this observation with a curious superior distance which denies any understanding or sincerity.

All of a sudden my eyes are becoming bleary, and my fingers are becoming numb. I must stop soon . . . well, you get the picture . . .

Once more into the breach:

Some historical errors: about one third of the Russian Doukhobors migrated to Canada, Mr. Morrow later changes this to half, his origin of the Doukhobors does not mention Bogomils or the Massaliani in Slavic documents of the 13th century, or the Essenes, or the cave dweller who tossed the Bible into the Volga.

[See: www.larrysdesk.com/]

Most of the Doukhobors did accept Illarion Pobirokhin as ‘filled with Christ’s spirit’, what Mr. Morrow does not understand is the Doukhobor concept of the ‘divinity within’ and the principle of PARIA SUNT, QUAEDAM SUNT ALIIS AEQUALES .

[See: http://www.larrysdesk.com/words-of-wisdom.html]

There was no government sponsored education under Alexander I. In 1830 Nicholas I gave them an ultimatum of joining the Orthodox Church and swearing an oath of allegiance or further exile; mutilated bodies and purported murders had nothing to do with this. Peter Verigin became their spiritual leader when Lukeria Kalmikova died in 1886 [not 1884], and not 1902 when his exile was completed. Lukeria named him ‘Lordly’[imbued with the Lord] when he was an infant, not the Doukhobor followers years later.

The move to BC is portrayed as voluntary because Verigin had purchased land there, how did his research miss the government seizure of the lands in 1907 originally granted under the Hamlet Clause?

[See: http://www.larrysdesk.com/hsmbc-plaque-unveiling.html]

No, Peter Verigin did not expound on ‘land belonging to God’, this was a Sons of Freedom concept. In fact, he was Chairman of the CCUB, the largest communal experiment in North America which contained 71,600 acres in the three western provinces valued at $11,000,000.

Now I am going bonkers . . .

As mentioned earlier, Mr. Morrow cites some excellent references, why on earth did he not read some of them? The errors mentioned are only a sample and now I am too fatigued to continue, I must read a real book . . .

At the end of this apologia, we are left with the quixotic question: Did you stop beating your wife? Those Doukhobors who lived and laboured in ‘peace and prosperity’ had nothing to apologize for although they falsely suffered unfair recriminations. Why the mistaken assumption, that there was something wrong with them? They do not need a self aggrandizement apology by way of recognition except to be recognized as normal citizens which most of them were.

It appears that the explanation should be on the other foot. It also appears to be the case of one hand clapping for the other hand but missing each in the process.

Could Mr. Morrow turn to his literary skills once more and try to explain why he and his fellow citizens were so blatantly ignorant and prejudiced? I believe he would be well positioned to do this.

Such reminisces as presented would be better confined to rambling dissertations in an easy chair in front of the fireplace on a cold winter evening, glass of scotch in hand, rather than exposed in the harsh reality of print purporting to be sympathetic, authoritative accounts.

In the back cover blurb, Koozma Tarasoff proclaims: ‘ . . . reveals many little known truths in order to set the record straight.’

I did not detect any.

And I did not finish this review . . . nothing more need be said . . . I did not find the pearl . . . sleep enveloped me . . . when I awoke, it was Dr. Martin Luther King Day . . . I had a dream . . .

A Tribute to Good Citizens

Ken Morrow

Recently, a professor friend of mine asked for my opinion on a book he was reading. I recalled that I thought it was quite flawed. Could I be more specific? I was going away on a week’s retreat, so I said I would try to locate the book and find some specific examples. Then, I began to write a review:

Dr. Morrow [optometry] cites a substantial bibliography at the end of this slim volume [142 p.] as well as no less than thirteen personages in his ‘Acknowledgments’. With that in mind, I concluded that he should have made some use of these sources. I also wondered why some of his historical consultants did not review the manuscript before it was published with their congratulatory remarks?

Let’s check out the images first:

P. 69: Peter V. Verigin was born July 28, not July 12 as reported here.

P. 71: The date cited is incorrect. The explosion that killed Peter V. Verigin occurred on October 29, 1924, not October 28, as stated. The photo does not look like a damaged railway car.

[See: www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/verigin/explosion/3d/3158en.html]

P. 72: This photo shows the burial image of Peter P. Verigin in 1939, not Peter V. Verigin in 1924.

P. 87: Doukhobors building a road . . . The caption is simplistic. One of the features of the Russian commune mir system was a broad thoroughfare between two rows of houses. Here communal animals such as chickens and cows could be corralled and herded, assemblies could be held, as well as fenced off protected areas for gardens maintained. There was little demand for roads as there was little traffic as we know it. It is also worth noting that for the most part, as can be discerned in the image, this work was done by women, children and elders while capable menfolk worked for wages to buy seed and implements for farming.

P. 89: Some thatching was done by Doukhobor settlers, but this was more prevalent among independent Ukrainian folk. A more appropriate early dwelling would be the zemlanka, emergency dwellings made by digging out shelters from hill sides.

[See: www.doukhobordugouthouse.com/ ].

P. 90: A well known image but misleading caption: The women, plowing sod in order to plant gardens, were not plowing because of a shortage of horses. There were no horses for this work, and the energetic women, realizing that they would be facing starvation without gardens, took it upon themselves to break the virgin sod.

P. 92: I have serious doubts about the accuracy of this picture. As far as I know, the Doukhobors in B. C. did not wear the military style caps, they were gone by then. This could be early Saskatchewan or even Russia.

P. 93: The date of this photograph is not correct. It is most likely c. 1927, showing Peter P. Verigin with his wife and mother and John J. Verigin Sr, his adopted son, when he arrived in Canada.

THE TEXT:

Mr. Morrow begins his rambling recollection by stating: the Greek Orthodox Church on P. ix. This should be Russian Orthodox Church.

On P. 2 Mr Morrow states that: ‘Inaccurate and misleading recorded and spoken historical information continues to negatively affect these God fearing, hard working people today’. However, as the reporter ‘on the ground', he does not cite any of this written or spoken information, but rather goes on to present more inaccuracies.

[See: http://www.larrysdesk.com/doukhobors-and-the-media.html].

He recalls some Doukhobor friends he had in school. It appears that he accepts Doukhobors as friends because they seem to be almost like him. He does little to discover their beliefs or culture, and on P. 7, he treats his Doukhobor friend to a hamburger, someone who most likely was a vegetarian, existing, as he says, on ‘cans of soup or spaghetti’. Should he have considered this diet further before his ‘treat’?

Earlier, on P. 5, he says: ‘During my five years of high school I knew of only one Doukhobor boy who had a date with a non-Doukhobor girl’. Presumably, he himself continued this segregation, although on P. 4 he quotes his friend who speaks knowingly about a girl who ‘gives me and my friends sex. Why can’t you?’; this to Mary Voykin, who refused to give them sex. Presumably she was not ‘dating’ material.

Throughout the book he continually refers to the Doukhobors’ lack of education and poor use of English. Growing up in Alberta, we were taught that an accent usually indicated that the speaker knew another language, and it was not a cause for derision. In Mr. Morrow’s ‘British’ Columbia, it appears to be a serious handicap. In most immigrant communities, little would be made of this. [See: As The Crow Flew, compiled by Larry Ewashen, in which thirty-five separate nationalities lived harmoniously side by side and celebrated this by having an inter group annual banquet where all of the various groups contributed ethnic food].

[See: http://www.doukhoborstore.ca/html/books.htm]

While decrying the lack of compassion and understanding of the Doukhobor immigrants by himself and others, he describes how he joined the hilarious abuse of this group by locking an ‘illiterate ignorant’ Doukhobor gardener in his grandmother’s outhouse. [P. 10]

P. 15 - 16, he presents a mistaken view of the Doukhobor concept of God. While this particular Doukhobor may have believed in a manipulative, dictatorial God, this is not part of the belief system, although the concept of the ‘God within’ is. To compound his lack of compassion and sensitivity, he reports this incident with a smug superiority, prefacing his report with: ‘He exclaimed in a very loud broken English in a high pitched voice that could be heard all over the bus’. Oh horrors, Dr. Morrow possibly observed talking to a Doukhobor!

Perhaps Mr. Morrow should have investigated further, as in this case his report is totally superficial, similar to an earlier reference to a funeral where the Doukhobors essentially sat at tables and ate all afternoon. [The Doukhobor funeral is replete with specific rites and it is apparent that he has missed this completely].

This is the consistent superficial tone throughout, so aside from trumpeting his own superiority, I really wonder why he bothered to write this shallow portrayal? The Doukhobors only needed to be normal people as they were, it was Mr. Morrow and his fellow citizens who appear to be suffering from an innate inability to treat people with equality and respect. No doubt this is an impression that Mr. Morrow did not intend to convey, but this becomes evident as one proceeds through this dreary diatribe.

He then goes on to describe how a Doukhobor neighbour poisoned his dog, Bertie, although no proof aside from general gossip is offered. Herein, also lies the basic racist tone of the tome: If I suspected my neighbour of taking a saw to my dog [as Jimmy Carter did when the dog ate his cat’s food], would I say, my neighbour, the Rosicrucian, attacked my dog, or would I say, my neighbour attacked my dog? What is the Rosicrucian reflection on the matter, are we to surmise that all Rosicrucians are attackers of dogs or all Doukhobors [likely] poison dogs?

Along the way he condemns the anarchistic protests of the Sons of Freedom, without any research into the grievances that stimulated such actions.

[See: www.larrysdesk.com/hope-history-conference-bridging-the-past.html ]

He then mentions a man from the east who married a Doukhobor woman because he he did not know who the Doukhobors were, Doukhobors who condemned the Sons of Freedom and Doukhobors who joined the Protestant church.

All this and I am only to page nineteen, and all this observation with a curious superior distance which denies any understanding or sincerity.

All of a sudden my eyes are becoming bleary, and my fingers are becoming numb. I must stop soon . . . well, you get the picture . . .

Once more into the breach:

Some historical errors: about one third of the Russian Doukhobors migrated to Canada, Mr. Morrow later changes this to half, his origin of the Doukhobors does not mention Bogomils or the Massaliani in Slavic documents of the 13th century, or the Essenes, or the cave dweller who tossed the Bible into the Volga.

[See: www.larrysdesk.com/]

Most of the Doukhobors did accept Illarion Pobirokhin as ‘filled with Christ’s spirit’, what Mr. Morrow does not understand is the Doukhobor concept of the ‘divinity within’ and the principle of PARIA SUNT, QUAEDAM SUNT ALIIS AEQUALES .

[See: http://www.larrysdesk.com/words-of-wisdom.html]

There was no government sponsored education under Alexander I. In 1830 Nicholas I gave them an ultimatum of joining the Orthodox Church and swearing an oath of allegiance or further exile; mutilated bodies and purported murders had nothing to do with this. Peter Verigin became their spiritual leader when Lukeria Kalmikova died in 1886 [not 1884], and not 1902 when his exile was completed. Lukeria named him ‘Lordly’[imbued with the Lord] when he was an infant, not the Doukhobor followers years later.

The move to BC is portrayed as voluntary because Verigin had purchased land there, how did his research miss the government seizure of the lands in 1907 originally granted under the Hamlet Clause?

[See: http://www.larrysdesk.com/hsmbc-plaque-unveiling.html]

No, Peter Verigin did not expound on ‘land belonging to God’, this was a Sons of Freedom concept. In fact, he was Chairman of the CCUB, the largest communal experiment in North America which contained 71,600 acres in the three western provinces valued at $11,000,000.

Now I am going bonkers . . .

As mentioned earlier, Mr. Morrow cites some excellent references, why on earth did he not read some of them? The errors mentioned are only a sample and now I am too fatigued to continue, I must read a real book . . .

At the end of this apologia, we are left with the quixotic question: Did you stop beating your wife? Those Doukhobors who lived and laboured in ‘peace and prosperity’ had nothing to apologize for although they falsely suffered unfair recriminations. Why the mistaken assumption, that there was something wrong with them? They do not need a self aggrandizement apology by way of recognition except to be recognized as normal citizens which most of them were.

It appears that the explanation should be on the other foot. It also appears to be the case of one hand clapping for the other hand but missing each in the process.

Could Mr. Morrow turn to his literary skills once more and try to explain why he and his fellow citizens were so blatantly ignorant and prejudiced? I believe he would be well positioned to do this.

Such reminisces as presented would be better confined to rambling dissertations in an easy chair in front of the fireplace on a cold winter evening, glass of scotch in hand, rather than exposed in the harsh reality of print purporting to be sympathetic, authoritative accounts.

In the back cover blurb, Koozma Tarasoff proclaims: ‘ . . . reveals many little known truths in order to set the record straight.’

I did not detect any.

And I did not finish this review . . . nothing more need be said . . . I did not find the pearl . . . sleep enveloped me . . . when I awoke, it was Dr. Martin Luther King Day . . . I had a dream . . .