DOUKHOBOR LAND SEIZURE

CANADA AT LAST!*

Aylmer Maude, Tolstoyan and early activist in the Doukhobor migration, wrote in New Order: 211:11:

The migration of the Doukhobors is similar in character to the expulsion of the Huguenots from France, or the early Puritans to America . . . it is not a migration undertaken from economic motives so much as it is an escape from the house of bondage prompted by religious motives.

Most scholars of this period of Canadian settlement history would agree that the Canadian government found the Doukhobor settlers useful at the time of their arrival. There were different reasons for wanting to populate the vast territory between British Columbia and Ontario. First of all there was a newly completed railroad but little use for it across Canada. Commerce was needed, and wealthy Eastern families such as the Masseys and the Fergusons wanted a market for their farm machinery. The Riel Rebellion of 1885 was still a fresh memory and a populated mid west would enhance ‘civilization’. Then there was the US Manifest Destiny and a huge barren unprotected waste land with an open border. Already American opportunists were exercising squatters’ rights.

It is possible that conditions for the impending Doukhobor exodus of 7,500 souls was sent by Verigin in exile, and was passed on by the Doukhobors, Ivin and Makhortov, who first came to Canada to survey the suitability of potential land. These conditions also appear in a letter from Tolstoy to Mavor.

The conditions expressed were the following:

1. "No obligation for military service".

2. "Full independence in the inner organization of their lives".

3. "Land in a block settlement".

Their concern for full independence in the internal organization of their lives indicated their desire to maintain the traditional village commune, or Mir system in general. The Mir served as a unit of local economic government. It established and operated communal hay meadows and pastures, and made decisions concerning work to be undertaken in other parts in their farming practise in Russia. The Mir had additional functions: its treasury supported the sick and needy; it bought and rented land, and was responsible for the periodic redistribution and equalization of the members’ holdings.

The Canadian authorities understood that the Doukhobors wished to farm in block settlements, and that they would be group settlers. The latter implied that they could live in villages, under the auspices of the Hamlet Clause.

The Clause, enacted earlier for other communal settlers, stated that they would have to make improvements on their individual quarter-sections, although there was nothing to prevent them from making these improvements by communal labour.

The Clause stated: If a number of homestead settlers, embracing at least twenty families, with a view to greater convenience in the establishment of schools and churches, and to the attainment of social advantages of like character; ask to be allowed to settle together in a hamlet or village, the minister may, in his discretion, vary or dispense with the foregoing requirements as to residence, but not as to the cultivation of each separate quarter-section entered as a homestead.

The two chief conditions of the mass migration of the Doukhobors, who came with the reputation as the best farmers in the world under the most difficult circumstances, were seemingly easy to fulfill. They could not be soldiers, and they must have ‘land in a bloc.’ Canada had a conscientious objector act since 1875, their names could be added to the list, ‘land in a bloc’ seemed to be equally provided for, all of their homestead claims would be simply side by side.

However, in practise, the Canadian government seemingly did not, or chose not to understand that ‘land in a bloc’ to the Doukhobors meant independent administration of this ‘bloc’, including cultivation, construction of villages, and general administration and different uses of different portions of land within this bloc. In fact this was a third condition, ‘administration of their own affairs’, which they also took to include education.

So when the Doukhobors improved and developed over 600,000 acres under their communal ‘land in a bloc’ condition, the new Minister of the Interior, Frank Oliver, could simply enforce an existing previous law, the Homestead Act, and the Doukhobors would be compelled to relinquish their hard won land and move on, making it available for ‘more desirable’ British settlers from Ontario. [His words.]

The Homestead Act provided that each male, 18 years and over, was entitled to 160 acres of land providing he paid a $10. registration fee to the land agent. improved it [cultivated], and built a dwelling on it within three years. He then received patent, or ownership. Ownership came with becoming naturalized, i.e. swearing the oath of allegiance, thus becoming a British subject.

This was the desired homestead and settlement process envisioned by the Dominion government, designed to produce British subjects as quickly as possible. However, this procedure was temporarily put aside for the desired Doukhobor settlement under the provisions of the Hamlet clause.

But to what extent was this Hamlet clause allowed? The truth of the government’s intention appears to be far more complex and possibly devious. After agreeing to the conditions requested, as early as within a year of arrival, pressure was exerted on Doukhobors to register for land individually under the Homestead Act.

In 1900 a government agent states in a letter that to facilitate a plan to make them register individually, they will open land offices near the communal villages. In 1901, Commissioner of Dominion Lands Turiff writes to James Smart, Deputy Minister of the Interior: ‘ . . . my recommendation is . . . that our Agents set to work to manoeuvre a presence of a number of Doukhobors who are willing to make their homestead entries to where the land office is, five or six from each village that we may reasonably overcome . . . the greater bulk who have not yet agreed . . . these people are very much like sheep and when they find that certain of their number have taken certain action, they think it is all right to do the same.’

Another government agent referring to a letter from the Doukhobors, around the same time, wonders who Lukeria Kalmakova is, and notes that Peter Verigin is one of the brothers still in exile, but does not realize that Peter V. Verigin is indeed the leader of the group, and behind this emigration.

[If the government was sincere in honouring the requested conditions, would they have not made an effort to learn something about these people, their culture and history, and their condition from whence they came?]

Bonch-Bruevitch published his remarks on their treatment in his book, Doukhobori v Kanadskiikh Preriiakh (Doukhobors on the Canadian Prairies): ‘One became amazed at the carelessness and negligence of the Canadian Government, which, having sent into the wild prairie a large number of people who were acquainted neither with the region nor the language, did not trouble itself about the proper medical aid, or even about the organization of such aid to the settlement’.

These requests for individual registration were opposed by the Doukhobors, but the issue was further confused by Bodyanski, a Tolstoyan who believed in a strict communal non-ownership. [Bodyanski was subsequently arbitrarily deported.] It was he and a colleague who coached the Doukhobor petitions against land registration and registration of births and deaths and marriages.

A letter dated February 1901, written by the Commissioner of Immigration to Frank Pedley, Superintendent of Immigration, states: ‘ . . . Mr Bodyanski would be furnished with transportation from Yorkton to Liverpool on condition that he does not return . . .’. Presumably, Mr. Bodyanski accepted the offer, since he was not heard from again. Just an example of the ruthless power the Doukhobors were dealing with.

Leo Tolstoy himself, held in awe by the Doukhobors as a God-like benefactor, referred to as dedushka, [grandfather] further confused the issue, and the Doukhobors, by writing a letter to them in 1900 telling them to refuse individual land ownership. He was becoming increasingly hardened towards all state governments, and was cynical of the move to Canada, as he outlined in a letter to Chertkov, believing that the government of Canada was being merely opportunistic.

Further ignorance on the part of the government agents clouded the issue. In a letter in 1901, a delegation of Doukhobors writes explaining why they do not cultivate certain lands, and try to explain their idea of common land; the government edict requiring that each individual quarter section must be cultivated.

‘We repeat that we live like one farm. We’ll use the lands thus: . . . it is impossible for us to cultivate each portion; . . . one portion of the land goes for tilling, second for resting, that is, in time we’ll sow it, the third portion for mowing of hay.’

The Russian Mir or commune system regarded land as a common resource to be used by those working on it in a cooperative fashion, and this was the system that the Doukhobors were adamant to maintain and this is what they understood had been granted.

In its obstinance and ignorance of farming practise, the government seized certain sections that were not cultivated. Clearly they did not understand what the Doukhobors considered as ‘land in a bloc.’

On December 8, 1900, a Doukhobor Committee wrote to James Smart, Deputy Minister of the Interior: . . . ‘There is a hill called Thunder. It takes about 8 sections. It is no good for us. Do you deduct number of sections taken by this hill from the number of homesteads . . . ?’ This was a forested, mountainous hill not suitable for agriculture. In the reply, the government obfuscated the issue, essentially suggesting that they chose it as part of their settlement and they [the government] would like to hear more about it.

In 1901, in an unprecedented contradiction of the Doukhobor understanding, bilingual posters were placed in the villages exhorting the Doukhobors, those 18 years of age and over, to register for the land before it was too late. [?]

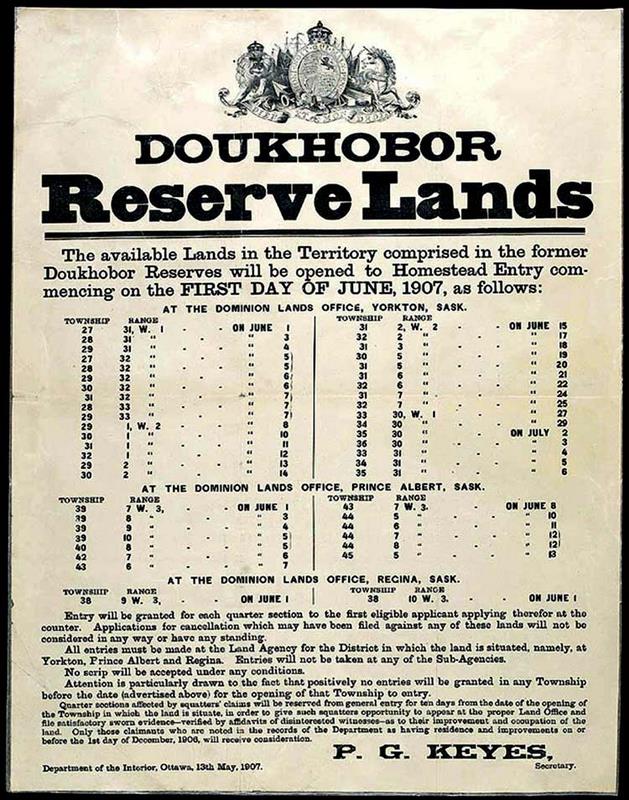

It is generally believed that the land loss began with the election of Frank Oliver in 1905, but as early as December 1901, a mere two years after their arrival, the following Public Notice appeared in Russian and English, posted in all of the villages:

‘ . . . NOTICE IS THEREFORE HEREBY GIVEN to all settlers in the above colonies that on or after the first of May, 1902, the lands referred to for which entry may not have been made, shall be thrown open for general homesteading . . . '

A clear misapprehension of what ‘land in a bloc’ was all about, or a convenient misinterpretation? Two different worlds and a chasm of misunderstanding in between.

In 1901, the Doukhobor women wrote to the government: ‘Enough for you to praise your own laws and authorities and exalt yourselves! Who is higher than the Heavenly King and God? God created heaven and adorned it with all the heavenly beauty; the sun and the sunbeams and moon and stars to His own glory and founded the earth on the waters, and adorned it with different flowers and created all the living on earth that they should praise Him and gave liberty to all the living and animals. High is our Lord over all tongues for His grace and His mercy abideth forever.’

A cockroach cannot give birth to a butterfly. A case of whimsy in the face of bureaucratic upper chin smugness and self-righteousness.

Under a cloud of oppressive paranoia generated by the peremptory about face of the Federal government, they retreated into the traditional system they knew best; life as it was lived in the Caucasus: no land registration and no interference from police or state officials demanding marriage registration, births and deaths. This had worked for them in the past until conscription and the oath of allegiance became an issue in 1892 under Nicolas the Bloody.

The Doukhobors had always functioned well when coalesced under enlightened leadership, and Peter Verigin, upon his arrival in 1902, diffused the situation. However, in spite of continuing registration at Verigin’s behest and an arrangement of proxy committee registration which he had arranged, the government gave no quarter and no hint of compromise.

In February, 1905, Verigin wrote to Alex Moffat, Acting Commissioner of Immigration, asking why certain entries were cancelled even after they were registered? In this case the reason given was that they were not cultivated, most likely fallow portions, ‘resting’.

On October 9th, 1905, the Minister of the Interior, Frank Oliver, was informed that the Russian Ministry of the Interior had resolved that the Doukhobors in Canada could now return to the Caucasus. One wonders if Oliver was spurred into further action with impunity, to encourage them to return. They were guaranteed passage, three times the land they had when they left, and absolute freedom of religion. The horse had bolted the barn door, and though it was still open, it was reluctant to return - once bitten, twice shy.

Then the local ‘desirable’ settlers, noting the success of the Doukhobor communal industry and eyeing their productive terrain, began a campaign of agitation against the Doukhobors.

On December 21, a P. Buchanan from Devil’s Lake wrote to Frank Oliver, maligning Verigin and encouraging a strong move against the Doukhobors: ‘Our whole salvation is to break up the company and to get each man on his own quarter section.’ He continues in this vein and ends up with more shots at Verigin, suggesting that he was sent to Siberia for criminal behaviour. Another student of history and international events, and no doubt, one of the ‘more desirable’ settlers.

Robert Smith, of the Good Spirit Lake district, protested in August 1900 that 100 good British families were in danger of losing their homes to " . . . the alien and servile Slav serfs of Europe [who are only one degree above the monkey for civilization, both in morals and honesty.]"

Smart's reply to Smith's letter was the following: You are aware, perhaps, that there has become provision in the Dominion Lands Act for numbers of settlers to join in villages and hamlets similar to the system adopted by the Doukhobors, and although on general principles this is a very unsatisfactory thing yet it is not so easy to do away with it when it is once established.

[A small number of malcontents had chosen an uncertain future as roustabouts in some of the villages, a few attempted to file for homesteads.] *

Sifton, an original supporter of the Doukhobor immigration, on November 15, 1902, wrote: ‘. . . the crux of the Doukhobor question is the village system, as long as the Doukhobors are allowed to live in villages they will not be Canadianized . . . if you have got the Doukhobors each on his own homestead like the Galicians I am of the opinion from practical experience of the Doukhobors that they will be a different people’.

Face to face inspections began. Commissioner of Immigration, J. Obed Smith, July 1, 1903, reported: ‘He [Verigin] was dressed impeccably in a short blue gabardine coat, and his trousers were encased in close-fitting grey leggings, piped with black cloth; from a silken cord around his neck hung a silver watch and a gold pencil, and a large fountain pen, which was secured in his coat pocket with loops of black cloth."

Further reports: Lands Files, vol. 754, # 494483, Harley to Smith, February 14, 1903. McCreary wrote: ‘The first question that came up was the land question and taking up their homesteads. Mr. Harley went fully into the land and homestead laws and explained to them what course they would have to pursue in making their entries as well as the duties they would have to perform to get patent for same also explaining to them they would have to become British subjects before they would be granted patent for their homesteads. This was for some time a sticker with them, also that they must obey ail our laws same as other people, . . . In fact I got a little hot at them at them and the way they were acting and I simply told them we were not children and be made fools of; that we had enough nonsense and we had now come to business. See them stare at me that I would talk to their great leader that way . . . For your information it may be stated that under the present arrangement those Doukhobors who have secured homestead entry may live together in one or more villages and instead of being compelled to cultivate each quarter section held by each Doukhobor, the land around the village itself may be cultivated and the work which would otherwise be required on each individual homestead; may be done altogether around the village’.

The inspectors suggested that individual cultivation would increase the Doukhobors' awareness of their status as individual land holders. Their advice was to accept the common cultivation on each individual homestead.

' . . . it would be the means of acquainting each member of the Community with the lands held by the Community, and curiosity would then impel them to discover the possessor of each parcel.

. . . Also the very large area these Communists entered upon and have held up to this present time, being 311,840 acres, and which they have made no effort towards the ownership of and state frankly that they are absolutely careless towards, is surely most direct evidence of the effect of this kind of communism . . . Another peculiarity which your Commission took notice of was that, with one exception, these Doukhobors have always picked the easiest places for the clearing of a few willows and thus making these fields and farms symmetrical they have not done. Go around, take it easy, seems to have been their policy all through their occupancy of land in Canada. This lack of enterprise we did not charge to their laziness but to their intense communism, "Why grub and clear for other men?"

In addition to the cultivation problem the Commission reported a second major obstacle to Doukhobor land ownership. Re-entry and subsequent ownership, the Commission recommended, should only be permitted if the Doukhobors became naturalized Canadian citizens. To become naturalized the Doukhobors had to swear or solemnly affirm an oath of allegiance.

Many of the Doukhobors firmly refused to become naturalized. Their refusal had direct historical experience. In 1894, when Tsar Nicholas II had requested that Verigin swear an oath of allegiance, Verigin had refused on the grounds that it was a sin to swear (by heaven or earth'. They insisted that if they naturalized and became citizens then they would be compelled to go to war. [Isn’t that what the oath stated?]

This they would not do, as some told us "We would die first". When we continued to reason with them they repeatedly told us "We do not want to own the land, all we want is to be permitted to make a living thereon". A simple affirmation of the oath was not mentioned to them in 1906.

McDougall did not place much emphasis on the Sifton concession of communal Hamlet Clause cultivation. It was given, he felt, to ease homestead entry in 1902-1903. Patent was based on ordinary conditions. " . . . While certain privileges such as hamlet occupancy and block cultivation and exemption from military service were said to have been given to them, yet in the fulfilling of homestead requirements and the application for patents for ownership these people were even as others and subject to the same law governing each case."

The Commission recommended that any Communist who would not proceed toward naturalization and proper residence on his homestead or in the vicinity of it, and who would refuse re-entry, be resettled on special reservations provided by the Dominion.

These reservations would be strictly for the Doukhobors' use, but not for their private ownership. They would consist of 17-20 acres of land per capita, depending upon the quality and locality of the land. These lands would be set aside for the Doukhobors' use without charge.

In October, 1906, Verigin, often accused of being autocratic and ruling the Doukhobor followers, left to visit Russia to check the sincerity of the Russian government’s offer to allow Doukhobors to return. In absenting himself when he did, he of course gave the Doukhobors free rein to deal with the land question as they wished without his guidance or interference. This would seem to indicate that he wanted to allow them to exercise their own initiative in his absence.

In a conversation with Frank Oliver in October, 1906, before he left, he asked if the Doukhobors might buy the lands they were on to avoid naturalization conflicts. Oliver said he was not sure there was such a provision, later saying how could he be sure the buyers all belonged to a specific village? He also reiterated that the Doukhobors could not fulfill their rights to quarter sections if they continued to live in the villages.

Verigin replied that some of this land was stumps and swamps and not suitable for cultivation at all, eventually they would plough the land and clear out some of the stumps. Mr. Oliver replied firmly: ‘I have to administer the law as it is in the book . . . there is no law to give villages now . . . ‘. When Verigin asked about activating some registrations that were made but not filed by the government, Oliver replied: ‘There is no Doukhobor reserve now.’

Verigin said that the Grand Trunk Railway is asking him for 4,000 men, does Mr. Oliver think that the railway would employ them? Oliver thought they would and did not see a problem of such men coming to Canada. It seems that Verigin wanted to see if he could hire people from Russia to work on the railway. One can only conjecture what might have happened to these 4,000 when the job was completed? Would they be sent back to Russia once their usefulness was over, as were some Chinese once the CPR was completed [15,000 Chinese were imported for the building of the CPR, a dead body for every mile of track]? Would they be encouraged to file for homesteads? Unlikely, since Oliver did not consider them ‘desirable settlers’. Would they eventually have joined the Doukhobors in BC? Possibilities but no conclusion, since the scheme did not come to fruition.

In Russia Verigin visited the benefactor, Leo Tolstoy, and also met with the Russian Minister of the Interior, Stolypin, to investigate the possibility of the Doukhobors’ return.

On December 28, 1906, Reverend James McDougall was appointed the Commissioner of Investigation and Adjuster of Land Claims for the Doukhobor lands. He was empowered to recommend the cancellation of homestead entries to the local Land Agents, who would make the actual cancellation. He was also empowered to receive application for re-entry, to issue receipts if homestead fees were paid, and to administer the naturalization oath. Entry fees paid by Community members were to be credited against re-entries made by either independents or Communists. The criteria for the cancellation of the homesteads was " . . . non-compliance of the entrant with the condition as to residence, or as to cultivation, or as to both conditions". In the final decision, the Sifton concession of group and proxy registration was not treated as a binding agreement.

During the summer of 1907, Michael White, who participated in the 1906 inspections of the Doukhobor lands, was sent by the Lands Branch to observe the Doukhobors in their reservation settlements. He concluded his report with a general statement on Doukhobor affairs: ‘It would be premature, however, to think that the Doukhobor question is being entirely disposed of. It might be so and it might be not. The future alone will show it, and for all our predictions as to what the Doukhobors are going to do, may prove to be incorrect because the Doukhobors are a 'peculiar people'. And not until the Doukhobors will cease to be a peculiar people will (sic) Doukhobor question disappear from the horizon. Doukhobors (sic) will need a constant watching until schools and contact with other settlers will transform them and make them think in the same way as an ordinary man does.'

White's conclusions summarized the direction and the outcome of the Doukhobor homestead crisis. The Doukhobor land policy implemented in 1907 was an attempt to eliminate Doukhobor peculiarities in regard to land ownership. It was hoped that they might then "think in the same way as an ordinary man . . . " The communistic tradition of the Doukhobors, which fostered Doukhobor differences to surrounding capitalistic society but was their chosen way of life, was hard hit.

McDougall recommended also that Independents, who had fulfilled the requirements pertaining to cultivation and residence, receive their patents if they agreed to naturalization. If any Independents refused to be naturalized, their homestead entries would be cancelled by June 1907, and they would also have to resettle on the reservations.

These recommendations, with minor modifications, became official policy early in 1907. The final decision on the Doukhobor homestead question was that the Doukhobors were subject to ordinary homestead [Act] conditions. The Doukhobor entries were to be cancelled as McDougall had recommended, and the Doukhobors were to choose if they wished to comply with regulations pertaining to cultivation or residence, or to live on government reservations. Oliver recommended that the reservations consist of 15 acres per village resident.

The Land authorities realized that the Doukhobors' economic system could not be tolerated in the west because it had no place in a rugged capitalistic and individualistic setting.

5 Debates, Frank Oliver re: the Hamlet and Co-operative Farming Clause; June 26, 1906, p. 1436:

‘ . . . certain privileges which were accorded under the Act as it stood at present, appeared to have outlived their usefulness. We do not think these rights should continue; so we have dropped out of this Act provisions in regard to the substitution of cattle raising for cultivation, the privilege of living in hamlets instead of on the land, and the privilege of co-operative farming. We do not propose to renew these privileges.'

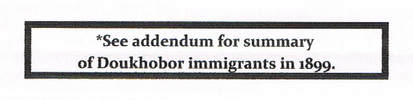

In 1907, the cancellation of nearly 300,000 acres settled by the Doukhobors triggered the greatest land rush in Canadian history.

* In 1802 Alexander 1 invited the Doukhobors for bloc settlement in Tavrida province. Those in prison were released providing they joined the exile. Many criminals proclaimed themselves Doukhobors preferring exile to prison life joined them. Migration to Canada 1899, found economic refugees once again.

When Peter Verigin arrived in Canada in 1902 he discovered many independent aspirants among the Doukhobor communes. Hoping that they would eventually realize the advantages of communal effort he redistributed them among the other villages.

After the cancellation of the Hamlet Clause the option of registering for individual homesteads was urged by government officials. Most of the Doukhobors rejected the idea. A minority, however, were anxious to take possession of prime agricultural land improved through communal effort.

When conscription loomed in 1917, Verigin was dismayed and felt betrayed when these deserters of the commune would seek to take advantage of the military exemption granted to the communal Doukhobors. If they were not granted exemption, he reasoned, they would once again seek refuge within the commune.

The government, anxious to break up the commune, granted them the exemption.

The conscientious objector act stipulated that the military objectors must belong to a recognized society, consequently, the dissidents formed many Doukhobor societies in Saskatchewan to meet these requirements, proclaiming themselves Independent Doukhobors.

Some sincere objectors gave up or sold their acquisitions and moved to B C, reunited with their families, and rejoined the communal Doukhobors.

SEE MORE: www.larrysdesk.com/queen-victoriafrank-oliverjames-mavormove-to-bc.html

SEE MORE: www.larrysdesk.com/tolstoy-speaks-essencetolstoy-verigin-dialoguelev-tolstoy-and-doukhobors.html

SEE MORE: www.larrysdesk.com/oath--bc-move-verigins-watch-gmo-speech-tolstoy-quotestudents--peace.html

SEE MORE: www.larrysdesk.com/tolstoy-speaks-essencetolstoy-verigin-dialoguelev-tolstoy-and-doukhobors.html

SEE MORE: www.larrysdesk.com/oath--bc-move-verigins-watch-gmo-speech-tolstoy-quotestudents--peace.html

*ADDENDUM:

SHIP NO. 1: S. S. LAKE HURON sailed Dec. 23, 1898 from the port of Batum on the Black Sea. Captain Evans headed the ship, while Leopold Sulerzhitsky was in charge of this first party. Ten died en route and one was born. After 29 days on Jan. 20, 1899, the ship arrived at the port of Halifax, Nova Scotia with 2,140 souls. Dr. Alexai Bakunin joined the group at Constantinople as did Alexandra Sats, student nurse and Nikolai Ziborov. Passengers included Grandfather Makortoff, 85, Gregory Bokov, and Dr. Mercer. and Prince Khilkov, a member of the advance negotiating group. Two Quakers, Joseph S. Eglinton and Job S. Gidley, Dr. F. Montizambert, Director General of Public Health and Quarantine Officer, among others, welcomed the group. Jan. 21 the ship was at Lawlor's Island for quarantine inspection and on Jan. 23 it was in St. John, New Brunswick, where the Russian dissidents boarded seven trains west.

SHIP NO. 2: S. S. LAKE SUPERIOR sailed Jan. 4, 1899 from the port of Batum piloted by Captain Taylor. Six died en route, arrival in St. John's, Jan. 26. Quarantined for 27 days because of one case of small pox. Arrived in Halifax Feb. 17. Saloon passengers were Count Sergius Tolstoy, Efrosinia D. Khiriakova, midwife and author. and Maria A. Chekhovich, midwife. Ship's manifest listed 829 passengers but actual estimate was over 2,000.

SHIP NO. 3: S. S. LAKE SUPERIOR with Captain Taylor sailed from Larnaca, Cyprus, April 18, 1899. One died and one was born on this 26 day voyage before arriving in Quebec City. May 9, 1899 with 1.036 registered passengers. Cabin passengers included Arthur St. John, Dr. Mercer and William Bellows from England along with Russians Miss Anna Rabetz, Elizabeth Markova, Anna Caroussa, Haratailo Andonew, and nurses Anna O. Rabets, and Alexandra A. Sats. The ship proceeded to Montreal for rail departure west.

SHIP NO. 4: S. S. LAKE HURON was the last ship of the largest mass migration of one group to Canada at that time. Under Captain Evans, the ship sailed from Batum May 24, 1899 and carried an official number of 2,286 Doukhobors. Twenty- nine days later it arrived in Canada, June 21. Most passengers came from Kars, many of whom financed their journey by selling their belongings. Passengers included Anastasia Verigin, Peter V. Verigin's aged mother. A group of anti-Tsarist Russians accompanied this party, including medical attendant Efrosinia D. Khiriakova, Alexander N. Konshin, Tolstoyan son of a wealthy Moscow merchant, and young Marxist Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, then known as V. Ol'khovskv. He proceeded to record Doukhobor oral history in Russia and Canada and in 1909 published the Zhvotnaia Kniga Dukobortsev [Doukhobor Book of Life]. Also his future wife, Doctor Vera M. Velichkina and nurse Maria Rabets. Due to smallpox they were quarantined on Grosse Isle in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, 30 miles from Quebec City. Quarantine ended June 29. July 3 and 4 the Doukhobors travelled west on several C. P. R. cars. Some 7,500 Spirit Wrestlers/ Doukhobors had finally arrived in their new land.

PRIMARY SOURCE: Public Archives of Canada, Immigration Branch RG76, vol. 185, file 65101, reels C 4519 and C 4517, also Vol. 18$, file 65101, part 4, reel C 7538. Inaccuracies re: dates arose when both styles of calender's were used for references. Here they are transcribed into the new Gregorian style which was 12 days ahead of the old Julian calendar. Regrettably, the manifest for the first ship is missing, apparently burned in the Winnipeg Immigration Branch Office. Seemingly, it had been sent there to verity pension applicants’ ages. Precise numbers of immigrants are difficult to verify because of stowaways and illegible information.

Koozma J. Tarasoff, CDS Newsletter, March 1997

SHIP NO. 1: S. S. LAKE HURON sailed Dec. 23, 1898 from the port of Batum on the Black Sea. Captain Evans headed the ship, while Leopold Sulerzhitsky was in charge of this first party. Ten died en route and one was born. After 29 days on Jan. 20, 1899, the ship arrived at the port of Halifax, Nova Scotia with 2,140 souls. Dr. Alexai Bakunin joined the group at Constantinople as did Alexandra Sats, student nurse and Nikolai Ziborov. Passengers included Grandfather Makortoff, 85, Gregory Bokov, and Dr. Mercer. and Prince Khilkov, a member of the advance negotiating group. Two Quakers, Joseph S. Eglinton and Job S. Gidley, Dr. F. Montizambert, Director General of Public Health and Quarantine Officer, among others, welcomed the group. Jan. 21 the ship was at Lawlor's Island for quarantine inspection and on Jan. 23 it was in St. John, New Brunswick, where the Russian dissidents boarded seven trains west.

SHIP NO. 2: S. S. LAKE SUPERIOR sailed Jan. 4, 1899 from the port of Batum piloted by Captain Taylor. Six died en route, arrival in St. John's, Jan. 26. Quarantined for 27 days because of one case of small pox. Arrived in Halifax Feb. 17. Saloon passengers were Count Sergius Tolstoy, Efrosinia D. Khiriakova, midwife and author. and Maria A. Chekhovich, midwife. Ship's manifest listed 829 passengers but actual estimate was over 2,000.

SHIP NO. 3: S. S. LAKE SUPERIOR with Captain Taylor sailed from Larnaca, Cyprus, April 18, 1899. One died and one was born on this 26 day voyage before arriving in Quebec City. May 9, 1899 with 1.036 registered passengers. Cabin passengers included Arthur St. John, Dr. Mercer and William Bellows from England along with Russians Miss Anna Rabetz, Elizabeth Markova, Anna Caroussa, Haratailo Andonew, and nurses Anna O. Rabets, and Alexandra A. Sats. The ship proceeded to Montreal for rail departure west.

SHIP NO. 4: S. S. LAKE HURON was the last ship of the largest mass migration of one group to Canada at that time. Under Captain Evans, the ship sailed from Batum May 24, 1899 and carried an official number of 2,286 Doukhobors. Twenty- nine days later it arrived in Canada, June 21. Most passengers came from Kars, many of whom financed their journey by selling their belongings. Passengers included Anastasia Verigin, Peter V. Verigin's aged mother. A group of anti-Tsarist Russians accompanied this party, including medical attendant Efrosinia D. Khiriakova, Alexander N. Konshin, Tolstoyan son of a wealthy Moscow merchant, and young Marxist Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, then known as V. Ol'khovskv. He proceeded to record Doukhobor oral history in Russia and Canada and in 1909 published the Zhvotnaia Kniga Dukobortsev [Doukhobor Book of Life]. Also his future wife, Doctor Vera M. Velichkina and nurse Maria Rabets. Due to smallpox they were quarantined on Grosse Isle in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, 30 miles from Quebec City. Quarantine ended June 29. July 3 and 4 the Doukhobors travelled west on several C. P. R. cars. Some 7,500 Spirit Wrestlers/ Doukhobors had finally arrived in their new land.

PRIMARY SOURCE: Public Archives of Canada, Immigration Branch RG76, vol. 185, file 65101, reels C 4519 and C 4517, also Vol. 18$, file 65101, part 4, reel C 7538. Inaccuracies re: dates arose when both styles of calender's were used for references. Here they are transcribed into the new Gregorian style which was 12 days ahead of the old Julian calendar. Regrettably, the manifest for the first ship is missing, apparently burned in the Winnipeg Immigration Branch Office. Seemingly, it had been sent there to verity pension applicants’ ages. Precise numbers of immigrants are difficult to verify because of stowaways and illegible information.

Koozma J. Tarasoff, CDS Newsletter, March 1997