Throughout my career I have written much poetry and stories in addition to archival and scholarly articles. With the pressures of paying work, the latter two remained, the former two were moved to the back burner. Now I am retired and there is no longer an excuse not to write a story. I hope you enjoy these:

PRINCE PHILIP AND I

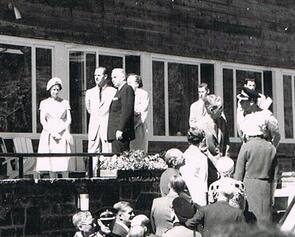

Lots of press over the recent demise of HRH Prince Philip, including interviews with anyone who knew him or encountered him. However, a multitude of scribes neglected to query me about my encounter with said RH, so I offer the following: Some years ago I was an aspiring thespian at the Banff Centre. While idling my time in the pristine grounds with exquisite company, a messenger intervened with a summons to the Director’s office; Senator Donald Cameron. As a scholarship student I surmised it was some technicalities regarding my status. The Senator was cordial and informed me that we were expecting notable company, and I was to fulfill a role. The Queen and Prince were stopping by on their Canadian tour, and I was to be the official guide to the Prince. They would be touring the facilities in two groups, the Senator in charge of the Queen contingent, and I was to guide the Prince, sans entourage. I was given a route map to follow and the next day, after a ceremonial welcome featuring the Banff Musical Ensemble, I was presented and we were off. As we were walking along we chatted informally, and I found he was [surprisingly I thought] well informed on the contemporary art and culture scene. As we entered one hallway we encountered two guys seemingly loitering in the corridor so I told them to move along - hallways must be clear. You won’t be telling us, we’ll be telling you, they said; we’re from Scotland Yard. We went on, joined by the reinforcement; took in some part of an opera voice exercise, a theater rehearsal, then came to the solarium; about fifty ballet dancers were gyrating below. As I began to explain the next scene and proceeded to move on, His Royal Highness said: I say, I think we’ll just watch this for a while, they can catch us up here. Out voted by the force of his stature we settled down to wait 'here,' while the Scotland Yard set out to find the Queen to tell her where we were.

A MEMORY TRIP DOWN

COWBOY TRAIL - Highway 22

Some time back, Lorne Eckersley of the Creston Valley Advance, wrote an article about a trip down Highway 22 in Alberta. His article brought back many memories to me.

Our ranch was about 3 miles west on Chapel Rock road, no road sign then. From there we rode horseback seven miles daily winter and summer to Chapel Rock School in the shadow of Mount Livingstone [not named for the ' . . . I presume.' gentleman but for Sam Livingston, pioneer farmer at Fort Calgary, 1872].

A highlight of our school days was an annual hike which included riding to the tree line, then climbing the summit of Livingston Mountain. From there we could see Lethbridge, 90 miles away.

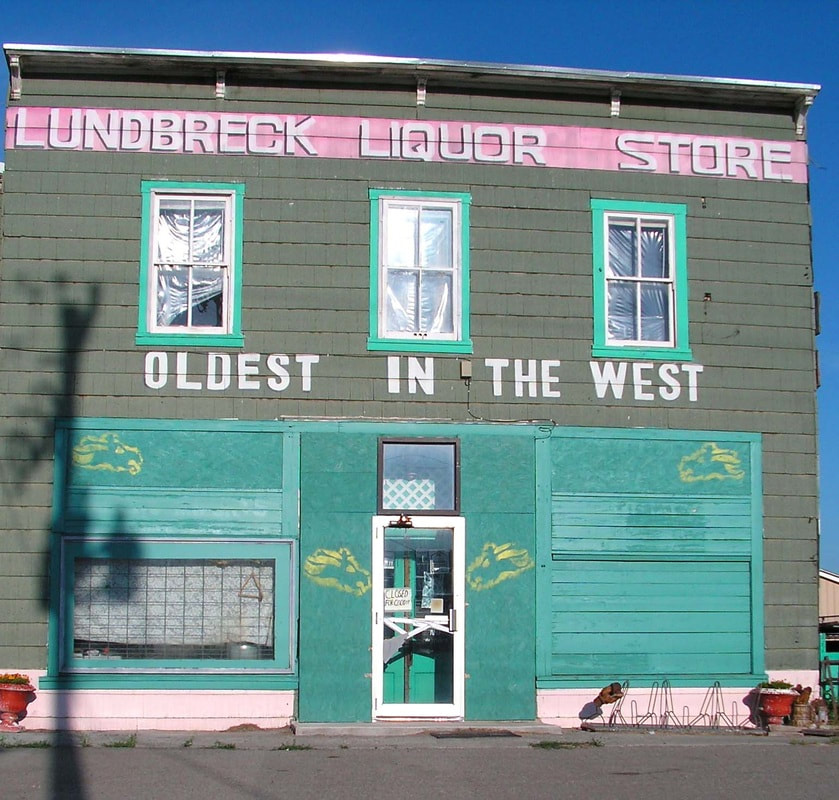

In those days, Highway 22 was not the scenic drive it is today. It was an ungraded road allowance track which served yearly cattle drives from the Waldron, A7, King ranches and the Maycroft Crown grazing lands, to the rail way and the Community Auction Sales at the end of the road in Lundbreck.

When you were able to work at the cattle auctions, you were graduating into manhood, and when these wild cattle [not domesticated like the milk cows on the farm] took after you when you were trying to herd them, your only refuge was a spirited leap for the top corral rail.

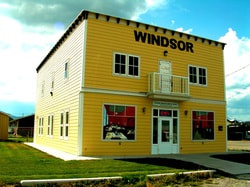

In the evening after the sale the Windsor Hotel flowed with buckets of beer and after closing time, the revelries moved to the rooms upstairs. Sale proceeds moved to new wallets, scores were settled, and cowboys navigated their woozy way along a balustrade in the moonlight to the double story outhouses at the back. [I sometimes wondered what was happening to someone who might be using the facilities on the bottom level].

These historical outhouses are now at Heritage Park in Calgary. Locals, sensing tourist potential, rebuilt the outhouses when the Windsor Hotel was rebuilt to 3/4 scale as a Seniors' Centre after it burned to the ground.

A detail missing was the hitching posts in front, where I remember seeing saddle horses and teams tethered, when rurals paused for refreshment after purchasing staples from the Lundbreck Trading Company before heading back into the hills.

A detail missing was the hitching posts in front, where I remember seeing saddle horses and teams tethered, when rurals paused for refreshment after purchasing staples from the Lundbreck Trading Company before heading back into the hills.

At that time the road was snowed in for weeks at a time and I remember my older brother Alex riding horseback into town with friends to pick up mail and other essentials. Eventually, a snow plough club was formed and our father operated the plough along a major stretch of the highway to Lundbreck. Even then a blizzard might leave you stranded in town, and you stayed at the Windsor until things cleared up the next day.

Over the years the highway was gradually improved and eventually high graded and gravelled. I remember travelling the 'back road to Calgary sans gravel, and one time when it was raining, the mud was packing to such a degree onto the tires and under the fenders, that one had to stop and scrape the mud off to allow the tires to rotate.

After beginning studies at the U of A, one day working at home in the summer, I tried to cross the highway and it was blocked by three hundred sheep [our land was on both sides of the highway]. Lo and behold, it was a cohort from the U of A, herding sheep for the summer; these were destined for the railway station in Lundbreck, now long since gone.

Eventually, cattle liners replaced the cattle drives and no doubt, stimulated the need for a paved road.

Cruising along this scenic Highway 22 recently at the speed limit or above. a semi with two trailers made a move to pass and I wisely slowed down as he drove into oncoming traffic.

Over the years the highway was gradually improved and eventually high graded and gravelled. I remember travelling the 'back road to Calgary sans gravel, and one time when it was raining, the mud was packing to such a degree onto the tires and under the fenders, that one had to stop and scrape the mud off to allow the tires to rotate.

After beginning studies at the U of A, one day working at home in the summer, I tried to cross the highway and it was blocked by three hundred sheep [our land was on both sides of the highway]. Lo and behold, it was a cohort from the U of A, herding sheep for the summer; these were destined for the railway station in Lundbreck, now long since gone.

Eventually, cattle liners replaced the cattle drives and no doubt, stimulated the need for a paved road.

Cruising along this scenic Highway 22 recently at the speed limit or above. a semi with two trailers made a move to pass and I wisely slowed down as he drove into oncoming traffic.

Years ago, I had learned my lesson in Ontario. Setting off from Toronto on a film shoot with two vehicles, one of which was pulling a trailer with all of our equipment, we experienced a similar situation. As there was approaching traffic the truck driver reclaimed our lane, midway through his pass, sending our towing car and trailer off the road into the ditch with the result of trailer splinters and film equipment scattered beside the road for several meters. The truck driver did not stop.

Since then, 18 wheelers passing my vehicle, have made me nervous, and the current move to extend the length of the trailers in my view, is not a good one.

Ditto increasing the speed limit, particularly in these ecologically sensitive times. It appears that this is a cynical ploy by the government to further Americanize our country and to relieve pressure on the constabulary who do not enforce the current speed limit in any case. Now they won't have to worry about it.

Progress can be positive or negative, it is in the eye of the beholder and practitioner, often, though, it should be handled with due caution.

And what about the 'good old days?'

Since then, 18 wheelers passing my vehicle, have made me nervous, and the current move to extend the length of the trailers in my view, is not a good one.

Ditto increasing the speed limit, particularly in these ecologically sensitive times. It appears that this is a cynical ploy by the government to further Americanize our country and to relieve pressure on the constabulary who do not enforce the current speed limit in any case. Now they won't have to worry about it.

Progress can be positive or negative, it is in the eye of the beholder and practitioner, often, though, it should be handled with due caution.

And what about the 'good old days?'

MY SHORT-LIVED

ADVERTISING CAREER

The intercom telephone buzzed on my desk and the light flashed. With the keen-edged advertising mind that I had assumed over the past few weeks I knew something was up all right. Always up; it could never be down. A lot of nerve, too, that buzzing, to disturb my mid-morning slumber in such a fashion.

'Better be important, that's all,' I thought. A pinnacle of creativity such as myself needed rest.

Generally speaking, with a few odd exceptions, I started off the mornings overflowing with debonair enthusiasm.

I briskly stepped into my office sometime between 8:15 and 8:30. Quite often, the old vulture would have his door open, ominously surveying the unfortunate late arrivals.

I would give him a jaunty, oblivious; 'Good morning, sir!' while inwardly muttering obscenities. If neatly timed, my flashing smile would coincide exactly with one of the more descriptive nouns of the Queen's English. His great slack jaw would drop several notches and the folds of fat over his collar would give me a solemn acknowledgement of my existence.

'Warm bodies,' he had once remarked at one of their high, official meetings, referring to us copywriters.

I suppose it was the brisk walk to the subway in the chilly morning air, and me with no overcoat, that woke me up; or at least sufficiently so until I arrived at the foreboding concrete monster that just bordered on the slums of the city.

Upon arrival I would leisurely peruse the morning paper and drink coffee for about an hour; then the dank heat and a great exhaustion would overwhelm me and I would fall asleep.

No-one minded very much; except some of my conscientious comrades in arms, the ‘twenty-years-in-the-field’ veterans and the fawning ‘men-on-the-way-up’.

On one occasion I had returned to my desk to find an award on it; no doubt a creation considered by the donors as original, witty, and biting; the award stating a commendation for 'remaining awake and alert for two and a half consecutive hours.'

Quite often, I had a short stretch of slumber in the afternoon as well. The bosses seldom noticed this as generally it took them two hours or more to drink their lunch.

The buzzer kept on, I made a half-asleep grab far the receiver, feeling slightly guilty, much to my annoyance.

I had lost most such humane feedings shortly after starting my work at this place. I wondered how long it had been buzzing as I assumed a casual though dignified advertising pose and smoothly announced my presence into the receiver.

It was himself, the Production Chief an the line: ' . . . care to step into my office . . . ' routine; in the usual ponderous, albeit somewhat stern and matter-of-fact methodical tone, this time.

How he loved to put it on this man!

What in the hell did he want, and so early in the morning, too? A thoroughly boorish and inconsiderate awakening!

'Perhaps he has chosen this morning to terminate our relationship', I thought; in a momentous flash of insight. 'Perhaps he had decided not to tolerate my presence any longer; perhaps I was in for it, the full treatment . . . well, well, well, how interesting'.

As I walked between the cubicles that housed my fellow writers [reminding me of my agrarian upraising and chickens] I became aware of a slow panic sensation spreading throughout my body. In fact, the more I awoke, the more panic-stricken I became.

I started thinking over our relationship for the past two weeks or so. Were there any warning signs I had missed?

There had definitely been a gradual change over the period of time since my arrival. When I had my first interview with him, it was much simpler than my wildest dreams.

Recently fired out of a TV promo job for taking too much time off, my search for gainful employment was having a dry run. I gave up on newspaper ads [over qualified] and started calling executives directly, by-passing the ‘human resources’ department.

I had found out his name and had called him directly; told him I was a writer and was interested in a job with his firm.

Upon my arrival, he waxed cordial; no doubt thinking the fame of his company was spreading far and wide; and I must be a very sensible young man indeed, to be interested in working for him.

[Most human beings can be flattered into anything, under the right circumstances. I had discovered this in my late night adventures.]

He didn't even look, fortunately, at my hurriedly prepared samples of the night before.

'You look like a writer’, he had proclaimed ostentatiously. Joseph Levine signing up a recently discovered movie star for a ten-year contract.

I had embarked upon a glorious new career the following morning.

We were quite friendly at first. Perhaps he regarded me as some sort of protege. Sometimes I had to struggle hard to control my inward feelings about this man. He couldn't have had much of an idea of how ridiculous he looked. He was doing such a smooth job of being friendly for both of us, anyway, he hardly needed my assistance. Sometimes he went so far as to share his coffee-break with me; exercising all of the solemnity and protocol of an entertaining maharajah.

Such distinctions he usually reserved far the twenty-year men or fellow-executives, or his own superiors when it seemed convenient. Quite a man, this specimen.

At that time he had watched my work closely and I had caught on to the techniques very rapidly, carefully pacing myself to show constant improvement and avoiding false expectations. In other words, I had to play dumber than I was.

After a time, contact between us became less frequent. I didn't find this upsetting, and I hardly missed his peering, watery eyes. I had assumed that he was sufficiently impressed with my work and had decided that close supervision was no longer required, though his efforts in the direction of supervision left a lot to be desired.

But now, all of a sudden, the truth of it all was facing me. It was the end of the line. The end of what, until this time, had appeared to be a promising career in advertising.

I was washed up, finished, and at my tender age too. Some of my fellow workers had even warned me that my stay was limited. Others would have loved to witness my departure. I was disturbing the normal, ritualistic, office routine of hard, diligent work, matched by a cringing awe of the boss.

I had attributed my lack of popularity among such people to jealousy of my exalted position and talent. After all, I did do more work half asleep in one day than they did in a week, didn't I?

But this? This was hard truth . . . a fish of another colour; not easily to be caught and fried . . . a shark? Come to think of it, he did bear a striking resemblance to a hammerhead shark.

I then remembered the way he had looked at me a couple of days ago. I should have realized it then; the way he seemed to be turning me over in his mind. At the time I had thought he was beaming with delight at the fact that he had hired me; probably thinking: 'Now there's a man I'm glad I found, he will go places.'

I must have been dreaming, living in a world of illusion and innocence; now I had to face the truth. He had probably been thinking about firing me right there.

I thought of the many debts that had forced me to take this job to begin with; and which somehow had grown larger in the meantime. I was in the process of discovering that I had a very flexible habit of living in a manner in which I had not been accustomed to. The fast lane . . . ?

His door loomed ahead of me, and had I not lacked faith in celestial powers I would have crossed myself as I approached it. I fought the urge to genuflect in front of it; by this time I was somewhat lacking faith in myself. I simply belched instead and opened the door; come what may, throwing caution to the winds, as it were. I was entering the lion’s den and I feared that it was I who was to be bearded.

Although I was the master of the gay repartee I knew it would be useless when matched against this merciless tyrant.

"Sit down, sit down," said the dashing, debonair, fishy look. 'Down gently with a crash, is it?' I thought. 'Well, you old wall-eyed martini-guzzling moron, you don't have to prepare me for your shattering revelations. I've seen your type too often, I'll get by, I've done it before.'

This was almost as much an illusion as it was a reality.

I had been doing some singing and playing in the local clubs as well as some small time theater with modest success. The pay wasn't much, but the work and people fascinating and seductive. It kept me sane and off the street, and sometimes out of the bars. These late night adventures were the reason for my dozy mornings. You can lead a horse to water but . . .

'I’ll get along,' I mused, 'I'll do it full time, that's really what I want to do anyway. When I make it big I’ll come back to this rat-infested jungle and tell him what I think of his job.'

Many times in my mind I had gone over this speech to him. 'I hate advertising,' I thought, building myself up to a feverish pitch; 'It's immoral, unethical, it smells of lies, hypocrisy, prostitution, and so on and so forth, I'm too good for it anyway.'

Slowly and deliberately, while he went through the routine of shoveling through his papers, I built myself up to an ecstatic pitch; preparing myself for the worst. The way he was keeping me waiting was undoubtedly one of his little tricks to make me feel uncomfortable.

'Well, it's like a parasite living off off human gullibility, a leech, better to starve than help this man in his insidious designs; what was I doing here? Why was I sitting here in this parasite's office?'

The four-hundred dollar suit looked at me, like a hound licking its chops; opened its mouth: "You know the ad you did on the boat?"

My toes contracted.

It was all a joke, that ad. I had written a cliche-ridden ad using all of the standard advertising exaggerations and every tried and true catch phrase I had ever run across because my original, and rather sophisticated copy, had been returned. I had submitted this re-write for a laugh, and there It was in front of him, and he was using it as an excuse to make it an issue.

"Uh . yes . . . ", I bantered suavely, to his inquiry.

"Did you ever see it?" he said pedantically; all the grace of a snail worming its way across a rotten board. I could tell he was warming up slowly.

"Well, of course, in its final stages, but it isn't printed yet."

I would play his game.

"I mean the boat," he proclaimed condescendingly; in a voice that seemed to imply 'idiot' and; ‘It never will be printed.'

I was on to him, all right. Knowing the ad was a joke, he was going to take it seriously, then use that as an excuse to fire me.

And then, to reinforce his self-righteousness, the business about seeing the boat. The instructions were explicit on writing about merchandise; one must be sure to see it before one wrote the ad.

I had had doubts about this procedure shortly after I had tried it. The observation of most of the merchandise was enough to destroy any imaginative enthusiasm one could have in writing about it. I had wisely reverted to seeing as little of it as possible, fantasy and idealism worked best for me, much to the benefit of the copy I wrote.

Thus, in dream-like fantasy one could conceivably write fairly convincingly about some of the products. The shocking reality of coming into contact with them usually destroyed such illusions. And now, although I'd been doing this for his own good, he was going to use it, along with other, things, against me.

"Well, no . . . I've never seen the boat," I countered smoothly; feeling like a prisoner turning on his own switch in the electric chair.

"You should have a look at it, we've got one in stock, you know."

Of course I knew.

"Did I make an error?" I asked, in what I thought was a nonchalant, off hand fashion.

"I was dreadfully busy at the time," I added convincingly.

If he was prepared to take it seriously, so would I.

The curdled smile opened again. 'Now he's going to let me have it', I thought. 'Here it comes.'

"Not really an error . . . but . . .’

I stared at him.

"Have a look at the boat, the ad's far too good. You see, my boy, we're selling it for five hundred dollars, the truth is, it isn't worth three. The ad builds it up a little too much, you see?"

I was beginning to see alright.

"Well, was I inaccurate?', I asked, hoping that I didn't sound too relieved.

"Well, not really inaccurate, just a trifle misleading; you didn't really say anything untrue."

"I thought that was the idea," I said briskly, pressing my advantage.

"Well, it Is, it Is, but tone it down just a little. Not too much, mind you, we've got a few hundred to move, but quite frankly," and he leaned towards me, "The boat's a piece of crap."

Sensations of relief flowed through my body. Ha, I had beaten the old scoundrel at his own game. A close one, though.

And now I could return to my slumber, free once again.

I thought over our little encounter as I walked back to my office.

I sat down in relief, but then, almost reluctantly, my hand pulled open my desk drawer and I slowly began cleaning out my desk.

ADVERTISING CAREER

The intercom telephone buzzed on my desk and the light flashed. With the keen-edged advertising mind that I had assumed over the past few weeks I knew something was up all right. Always up; it could never be down. A lot of nerve, too, that buzzing, to disturb my mid-morning slumber in such a fashion.

'Better be important, that's all,' I thought. A pinnacle of creativity such as myself needed rest.

Generally speaking, with a few odd exceptions, I started off the mornings overflowing with debonair enthusiasm.

I briskly stepped into my office sometime between 8:15 and 8:30. Quite often, the old vulture would have his door open, ominously surveying the unfortunate late arrivals.

I would give him a jaunty, oblivious; 'Good morning, sir!' while inwardly muttering obscenities. If neatly timed, my flashing smile would coincide exactly with one of the more descriptive nouns of the Queen's English. His great slack jaw would drop several notches and the folds of fat over his collar would give me a solemn acknowledgement of my existence.

'Warm bodies,' he had once remarked at one of their high, official meetings, referring to us copywriters.

I suppose it was the brisk walk to the subway in the chilly morning air, and me with no overcoat, that woke me up; or at least sufficiently so until I arrived at the foreboding concrete monster that just bordered on the slums of the city.

Upon arrival I would leisurely peruse the morning paper and drink coffee for about an hour; then the dank heat and a great exhaustion would overwhelm me and I would fall asleep.

No-one minded very much; except some of my conscientious comrades in arms, the ‘twenty-years-in-the-field’ veterans and the fawning ‘men-on-the-way-up’.

On one occasion I had returned to my desk to find an award on it; no doubt a creation considered by the donors as original, witty, and biting; the award stating a commendation for 'remaining awake and alert for two and a half consecutive hours.'

Quite often, I had a short stretch of slumber in the afternoon as well. The bosses seldom noticed this as generally it took them two hours or more to drink their lunch.

The buzzer kept on, I made a half-asleep grab far the receiver, feeling slightly guilty, much to my annoyance.

I had lost most such humane feedings shortly after starting my work at this place. I wondered how long it had been buzzing as I assumed a casual though dignified advertising pose and smoothly announced my presence into the receiver.

It was himself, the Production Chief an the line: ' . . . care to step into my office . . . ' routine; in the usual ponderous, albeit somewhat stern and matter-of-fact methodical tone, this time.

How he loved to put it on this man!

What in the hell did he want, and so early in the morning, too? A thoroughly boorish and inconsiderate awakening!

'Perhaps he has chosen this morning to terminate our relationship', I thought; in a momentous flash of insight. 'Perhaps he had decided not to tolerate my presence any longer; perhaps I was in for it, the full treatment . . . well, well, well, how interesting'.

As I walked between the cubicles that housed my fellow writers [reminding me of my agrarian upraising and chickens] I became aware of a slow panic sensation spreading throughout my body. In fact, the more I awoke, the more panic-stricken I became.

I started thinking over our relationship for the past two weeks or so. Were there any warning signs I had missed?

There had definitely been a gradual change over the period of time since my arrival. When I had my first interview with him, it was much simpler than my wildest dreams.

Recently fired out of a TV promo job for taking too much time off, my search for gainful employment was having a dry run. I gave up on newspaper ads [over qualified] and started calling executives directly, by-passing the ‘human resources’ department.

I had found out his name and had called him directly; told him I was a writer and was interested in a job with his firm.

Upon my arrival, he waxed cordial; no doubt thinking the fame of his company was spreading far and wide; and I must be a very sensible young man indeed, to be interested in working for him.

[Most human beings can be flattered into anything, under the right circumstances. I had discovered this in my late night adventures.]

He didn't even look, fortunately, at my hurriedly prepared samples of the night before.

'You look like a writer’, he had proclaimed ostentatiously. Joseph Levine signing up a recently discovered movie star for a ten-year contract.

I had embarked upon a glorious new career the following morning.

We were quite friendly at first. Perhaps he regarded me as some sort of protege. Sometimes I had to struggle hard to control my inward feelings about this man. He couldn't have had much of an idea of how ridiculous he looked. He was doing such a smooth job of being friendly for both of us, anyway, he hardly needed my assistance. Sometimes he went so far as to share his coffee-break with me; exercising all of the solemnity and protocol of an entertaining maharajah.

Such distinctions he usually reserved far the twenty-year men or fellow-executives, or his own superiors when it seemed convenient. Quite a man, this specimen.

At that time he had watched my work closely and I had caught on to the techniques very rapidly, carefully pacing myself to show constant improvement and avoiding false expectations. In other words, I had to play dumber than I was.

After a time, contact between us became less frequent. I didn't find this upsetting, and I hardly missed his peering, watery eyes. I had assumed that he was sufficiently impressed with my work and had decided that close supervision was no longer required, though his efforts in the direction of supervision left a lot to be desired.

But now, all of a sudden, the truth of it all was facing me. It was the end of the line. The end of what, until this time, had appeared to be a promising career in advertising.

I was washed up, finished, and at my tender age too. Some of my fellow workers had even warned me that my stay was limited. Others would have loved to witness my departure. I was disturbing the normal, ritualistic, office routine of hard, diligent work, matched by a cringing awe of the boss.

I had attributed my lack of popularity among such people to jealousy of my exalted position and talent. After all, I did do more work half asleep in one day than they did in a week, didn't I?

But this? This was hard truth . . . a fish of another colour; not easily to be caught and fried . . . a shark? Come to think of it, he did bear a striking resemblance to a hammerhead shark.

I then remembered the way he had looked at me a couple of days ago. I should have realized it then; the way he seemed to be turning me over in his mind. At the time I had thought he was beaming with delight at the fact that he had hired me; probably thinking: 'Now there's a man I'm glad I found, he will go places.'

I must have been dreaming, living in a world of illusion and innocence; now I had to face the truth. He had probably been thinking about firing me right there.

I thought of the many debts that had forced me to take this job to begin with; and which somehow had grown larger in the meantime. I was in the process of discovering that I had a very flexible habit of living in a manner in which I had not been accustomed to. The fast lane . . . ?

His door loomed ahead of me, and had I not lacked faith in celestial powers I would have crossed myself as I approached it. I fought the urge to genuflect in front of it; by this time I was somewhat lacking faith in myself. I simply belched instead and opened the door; come what may, throwing caution to the winds, as it were. I was entering the lion’s den and I feared that it was I who was to be bearded.

Although I was the master of the gay repartee I knew it would be useless when matched against this merciless tyrant.

"Sit down, sit down," said the dashing, debonair, fishy look. 'Down gently with a crash, is it?' I thought. 'Well, you old wall-eyed martini-guzzling moron, you don't have to prepare me for your shattering revelations. I've seen your type too often, I'll get by, I've done it before.'

This was almost as much an illusion as it was a reality.

I had been doing some singing and playing in the local clubs as well as some small time theater with modest success. The pay wasn't much, but the work and people fascinating and seductive. It kept me sane and off the street, and sometimes out of the bars. These late night adventures were the reason for my dozy mornings. You can lead a horse to water but . . .

'I’ll get along,' I mused, 'I'll do it full time, that's really what I want to do anyway. When I make it big I’ll come back to this rat-infested jungle and tell him what I think of his job.'

Many times in my mind I had gone over this speech to him. 'I hate advertising,' I thought, building myself up to a feverish pitch; 'It's immoral, unethical, it smells of lies, hypocrisy, prostitution, and so on and so forth, I'm too good for it anyway.'

Slowly and deliberately, while he went through the routine of shoveling through his papers, I built myself up to an ecstatic pitch; preparing myself for the worst. The way he was keeping me waiting was undoubtedly one of his little tricks to make me feel uncomfortable.

'Well, it's like a parasite living off off human gullibility, a leech, better to starve than help this man in his insidious designs; what was I doing here? Why was I sitting here in this parasite's office?'

The four-hundred dollar suit looked at me, like a hound licking its chops; opened its mouth: "You know the ad you did on the boat?"

My toes contracted.

It was all a joke, that ad. I had written a cliche-ridden ad using all of the standard advertising exaggerations and every tried and true catch phrase I had ever run across because my original, and rather sophisticated copy, had been returned. I had submitted this re-write for a laugh, and there It was in front of him, and he was using it as an excuse to make it an issue.

"Uh . yes . . . ", I bantered suavely, to his inquiry.

"Did you ever see it?" he said pedantically; all the grace of a snail worming its way across a rotten board. I could tell he was warming up slowly.

"Well, of course, in its final stages, but it isn't printed yet."

I would play his game.

"I mean the boat," he proclaimed condescendingly; in a voice that seemed to imply 'idiot' and; ‘It never will be printed.'

I was on to him, all right. Knowing the ad was a joke, he was going to take it seriously, then use that as an excuse to fire me.

And then, to reinforce his self-righteousness, the business about seeing the boat. The instructions were explicit on writing about merchandise; one must be sure to see it before one wrote the ad.

I had had doubts about this procedure shortly after I had tried it. The observation of most of the merchandise was enough to destroy any imaginative enthusiasm one could have in writing about it. I had wisely reverted to seeing as little of it as possible, fantasy and idealism worked best for me, much to the benefit of the copy I wrote.

Thus, in dream-like fantasy one could conceivably write fairly convincingly about some of the products. The shocking reality of coming into contact with them usually destroyed such illusions. And now, although I'd been doing this for his own good, he was going to use it, along with other, things, against me.

"Well, no . . . I've never seen the boat," I countered smoothly; feeling like a prisoner turning on his own switch in the electric chair.

"You should have a look at it, we've got one in stock, you know."

Of course I knew.

"Did I make an error?" I asked, in what I thought was a nonchalant, off hand fashion.

"I was dreadfully busy at the time," I added convincingly.

If he was prepared to take it seriously, so would I.

The curdled smile opened again. 'Now he's going to let me have it', I thought. 'Here it comes.'

"Not really an error . . . but . . .’

I stared at him.

"Have a look at the boat, the ad's far too good. You see, my boy, we're selling it for five hundred dollars, the truth is, it isn't worth three. The ad builds it up a little too much, you see?"

I was beginning to see alright.

"Well, was I inaccurate?', I asked, hoping that I didn't sound too relieved.

"Well, not really inaccurate, just a trifle misleading; you didn't really say anything untrue."

"I thought that was the idea," I said briskly, pressing my advantage.

"Well, it Is, it Is, but tone it down just a little. Not too much, mind you, we've got a few hundred to move, but quite frankly," and he leaned towards me, "The boat's a piece of crap."

Sensations of relief flowed through my body. Ha, I had beaten the old scoundrel at his own game. A close one, though.

And now I could return to my slumber, free once again.

I thought over our little encounter as I walked back to my office.

I sat down in relief, but then, almost reluctantly, my hand pulled open my desk drawer and I slowly began cleaning out my desk.

CONVICTED BUT NOT CONVINCED:

A memory - a theatre group called Convicted But Not Convinced.

We were convicted, but we were not convinced that life in prison was conducive to reconstruction of lives. How could we demonstrate these convictions? It was the theatre - portray the life within the prisons to the people 'outside'. And our company would consist of those who had been in prison.

Our leader was a veteran of Russian prisons - five years for narcotic smuggling before his father managed to spring him. Solitary confinement, he could not speak Russian. He did his time before it did him though it was only a reprieve.

A variety of offenders. He did a political crime. Dick was recently released after ten years for manslaughter.

I was an actor, but found myself repeating the same roles in different plays. The imposers who masqueraded as theatre directors had missed out on their true calling as head waiters as they continued to serve half baked puddings to a warmed over audience. A talent less clique which hired each other, some armed with a foreign accent.

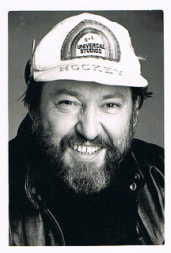

Films were worse. Cattle calls I attended featured a variety of Deliverance creeps as Hollywood North emulated Hollywood South. My rugged looks brought me work where talent didn’t count and I suffered from receiving money for catering to an appetite for violence, greed and sexploitation. I clung to the idea that there was hope for Canadian theatre but my idealism was rapidly fading.

I had written a thesis on drama in prisons and had toured shows in prisons and asylums. I believed that a sympathetic portrayal of parallel emotions acted out and the channeling of aggression in a controlled forum would relieve hostility. As we portrayed the uselessness of life inside, we would build an adjustment to life outside. We would leave the past behind by exorcising it through make believe. Theatre would be the bridge to the so called ‘normal’ life.

Part of this process was the public declaration of being a convict. This exposed, one could get on with facing reality rather than obfuscation and shame.

While our director was visionary, he lacked practicality, and I became producer and stage manager. My factotum was a reformed car thief who had found rehabilitation through my theatre school. I introduced him to Chekhov, and he seized on this discovery like a rabid ferret.

We were the core. Others drifted in and out, appeared or disappeared depending on their visions of time or police detainment - mostly peaceful offenders with a predilection for drugs, alcohol, gambling, and occasional thievery.

Our set and props were simple and claustrophobic - an iron bar cage in which the main action took place, props only as in prison. Stark, meager lighting heightened the drabness which was part of our message and suited our resources.

I was also the musician and songwriter. We illustrated tales that our ex-cons brought us - the night Bobby Landers died of a heart attack screaming for help while two guards sat and played cards. Such a scene would be enacted while I sang the song I had written; Bobby Landers Tonight. Sometimes we sang songs such as Go Down You Murderers, an English folk ballad, sometimes we sang of dangerous men such as John Hardy or an original number such as Joyceville Hotel.

Occasionally there was virtual reality. The unfamiliarity with theatrical convention in our company would enable real emotions to get the upper hand. Fists would fly, eyes might be blackened, once an arm was broken. After that, the perpetrator would break down, and end up sobbing: ‘I'm really sorry man, I love you man . . . '

The audience did not know how to react, was it real or make believe? Often it was both. This re-instated my belief that exciting theatre was still possible. Sometimes events were aided by the presence of police who had been tipped off that 'a group of cons were gathering for a rally'.

When we illustrated a jail break and a convict escaped, the audience would cheer. When we hunted him down in stylized fashion, often chasing him around the theatre, they would also cheer. The show was never the same, depending on where we were, which actors showed, and the audience reaction. Our leader's dog would join in the fray, barking and bounding throughout the theatre and joining the fights.

Our company, flexible, adaptive, used to living on the edge. We began to relate in a similar way to the outside, civilized smugness. Although now we were all ‘outside’, we lived our lives somewhat as though we were still ‘inside’.

Convicted but not convinced? We preached to the sympathetic converted, and only occasionally planted a seed of understanding. One of these blossoms turned out to be one of the spectator cops, who had originally come to observe and control if necessary - he went on to work with street people.

Our borrowed station wagon, strapped down with the prison bars, would arrive at the back door of a church basement. Volunteers would help move us in. Occasionally, we arrived at the front door of a three story coffee house, and here there were hangers-on and street people who were anxious to help, especially if they were invited to see the 'show' or play a small part.

Our 'rolling convict review' carried on throughout the summer, replacing members with recruits from the street and bars. We rolled along like a snowball down the hill, gaining momentum and gaining size. Word of our show spread slowly, but it spread.

One night, walking home from the Silver Dollar, we stumbled over an inert form. It was a native and we decided that Walter would be the native quotient to our show.

The Trial of the Dene was included - I will never forget when Walter appeared in front of the Judge, Jackie Burroughs, my friend the movie star.

When I first showed Walter the script he glanced at it and said 'I know all that . . . ' and handed it back to me. I surmised that he could not read, it would be best to let him improvise.

When Walter appeared on the charge of vagrancy he pleaded guilty: 'Of course I have nothing. You took my land, you took my kids, you took my animals, then you took my life, eh? now we don’t live in this world and our world is gone. Now you move my life inside so you take the thing was left - I belong outside. You have all now, the law is powerful and right and strong, and we are weak and lost, with no one to show us to the saving path'.

He let out a Hollywood style war whoop grabbing a fiddle and shouting; 'Let's dance, let's dance one more time'. We broke into a rag time two step, then two guards grabbed him and dragged him towards the cell. The audience stood up and yelled: 'Let him go, Let him go'

This is one of the highlights that I remember.

Near the end of the summer, the rolling snowball began to melt, and grew smaller as it neared the bottom.

Dick, our star, decided he was a boxer. He was not successful, but he carved out a niche for himself coaching street kids in the manly art. Score one for us.

Some of our best players, natural con men who had been convicted for fraud or dope dealing, found safer and more lucrative ways to break the law.

Our dene star grew tired of his role - it was too painful to recite the horrors of his life night after night - he gradually disappeared into the back alleys.

Our director discovered he had dementia. In a lucid moment he disappeared. His body was never found, but on the riverbank not far from the Don where the last executions in Canada took place around the time I had first come to Toronto, his faithful dog was discovered whimpering by the shore in starved condition.

My right hand man started his own theatre, 'socially relevant drama' dealing with abuse, mental incompetence and victims of circumstance and poverty.

I returned to a disgruntled acting career. I had sipped absinthe with the theatre gods, and now back to draft beer?

That fall at the Festival of Festivals, I received tickets for five films in which I appeared. I saw the first, and although it starred Richard Burton in one of his final roles, it was so abysmal I returned to the street without watching the others or hanging out at the reception with the beautiful people. I walked home thinking things over.

Unlike Pierre, I did not have the state of the entire country to consider, I only had the rest of my life.

I thought of Walter, our leader, the ferret, the boxer - that summer the theatre had lived.

They, the players in life’s production, had all made decisions for themselves, I suppose, and had moved on.

What was wrong with me?

- and so ended my theatre and film career.

A memory - a theatre group called Convicted But Not Convinced.

We were convicted, but we were not convinced that life in prison was conducive to reconstruction of lives. How could we demonstrate these convictions? It was the theatre - portray the life within the prisons to the people 'outside'. And our company would consist of those who had been in prison.

Our leader was a veteran of Russian prisons - five years for narcotic smuggling before his father managed to spring him. Solitary confinement, he could not speak Russian. He did his time before it did him though it was only a reprieve.

A variety of offenders. He did a political crime. Dick was recently released after ten years for manslaughter.

I was an actor, but found myself repeating the same roles in different plays. The imposers who masqueraded as theatre directors had missed out on their true calling as head waiters as they continued to serve half baked puddings to a warmed over audience. A talent less clique which hired each other, some armed with a foreign accent.

Films were worse. Cattle calls I attended featured a variety of Deliverance creeps as Hollywood North emulated Hollywood South. My rugged looks brought me work where talent didn’t count and I suffered from receiving money for catering to an appetite for violence, greed and sexploitation. I clung to the idea that there was hope for Canadian theatre but my idealism was rapidly fading.

I had written a thesis on drama in prisons and had toured shows in prisons and asylums. I believed that a sympathetic portrayal of parallel emotions acted out and the channeling of aggression in a controlled forum would relieve hostility. As we portrayed the uselessness of life inside, we would build an adjustment to life outside. We would leave the past behind by exorcising it through make believe. Theatre would be the bridge to the so called ‘normal’ life.

Part of this process was the public declaration of being a convict. This exposed, one could get on with facing reality rather than obfuscation and shame.

While our director was visionary, he lacked practicality, and I became producer and stage manager. My factotum was a reformed car thief who had found rehabilitation through my theatre school. I introduced him to Chekhov, and he seized on this discovery like a rabid ferret.

We were the core. Others drifted in and out, appeared or disappeared depending on their visions of time or police detainment - mostly peaceful offenders with a predilection for drugs, alcohol, gambling, and occasional thievery.

Our set and props were simple and claustrophobic - an iron bar cage in which the main action took place, props only as in prison. Stark, meager lighting heightened the drabness which was part of our message and suited our resources.

I was also the musician and songwriter. We illustrated tales that our ex-cons brought us - the night Bobby Landers died of a heart attack screaming for help while two guards sat and played cards. Such a scene would be enacted while I sang the song I had written; Bobby Landers Tonight. Sometimes we sang songs such as Go Down You Murderers, an English folk ballad, sometimes we sang of dangerous men such as John Hardy or an original number such as Joyceville Hotel.

Occasionally there was virtual reality. The unfamiliarity with theatrical convention in our company would enable real emotions to get the upper hand. Fists would fly, eyes might be blackened, once an arm was broken. After that, the perpetrator would break down, and end up sobbing: ‘I'm really sorry man, I love you man . . . '

The audience did not know how to react, was it real or make believe? Often it was both. This re-instated my belief that exciting theatre was still possible. Sometimes events were aided by the presence of police who had been tipped off that 'a group of cons were gathering for a rally'.

When we illustrated a jail break and a convict escaped, the audience would cheer. When we hunted him down in stylized fashion, often chasing him around the theatre, they would also cheer. The show was never the same, depending on where we were, which actors showed, and the audience reaction. Our leader's dog would join in the fray, barking and bounding throughout the theatre and joining the fights.

Our company, flexible, adaptive, used to living on the edge. We began to relate in a similar way to the outside, civilized smugness. Although now we were all ‘outside’, we lived our lives somewhat as though we were still ‘inside’.

Convicted but not convinced? We preached to the sympathetic converted, and only occasionally planted a seed of understanding. One of these blossoms turned out to be one of the spectator cops, who had originally come to observe and control if necessary - he went on to work with street people.

Our borrowed station wagon, strapped down with the prison bars, would arrive at the back door of a church basement. Volunteers would help move us in. Occasionally, we arrived at the front door of a three story coffee house, and here there were hangers-on and street people who were anxious to help, especially if they were invited to see the 'show' or play a small part.

Our 'rolling convict review' carried on throughout the summer, replacing members with recruits from the street and bars. We rolled along like a snowball down the hill, gaining momentum and gaining size. Word of our show spread slowly, but it spread.

One night, walking home from the Silver Dollar, we stumbled over an inert form. It was a native and we decided that Walter would be the native quotient to our show.

The Trial of the Dene was included - I will never forget when Walter appeared in front of the Judge, Jackie Burroughs, my friend the movie star.

When I first showed Walter the script he glanced at it and said 'I know all that . . . ' and handed it back to me. I surmised that he could not read, it would be best to let him improvise.

When Walter appeared on the charge of vagrancy he pleaded guilty: 'Of course I have nothing. You took my land, you took my kids, you took my animals, then you took my life, eh? now we don’t live in this world and our world is gone. Now you move my life inside so you take the thing was left - I belong outside. You have all now, the law is powerful and right and strong, and we are weak and lost, with no one to show us to the saving path'.

He let out a Hollywood style war whoop grabbing a fiddle and shouting; 'Let's dance, let's dance one more time'. We broke into a rag time two step, then two guards grabbed him and dragged him towards the cell. The audience stood up and yelled: 'Let him go, Let him go'

This is one of the highlights that I remember.

Near the end of the summer, the rolling snowball began to melt, and grew smaller as it neared the bottom.

Dick, our star, decided he was a boxer. He was not successful, but he carved out a niche for himself coaching street kids in the manly art. Score one for us.

Some of our best players, natural con men who had been convicted for fraud or dope dealing, found safer and more lucrative ways to break the law.

Our dene star grew tired of his role - it was too painful to recite the horrors of his life night after night - he gradually disappeared into the back alleys.

Our director discovered he had dementia. In a lucid moment he disappeared. His body was never found, but on the riverbank not far from the Don where the last executions in Canada took place around the time I had first come to Toronto, his faithful dog was discovered whimpering by the shore in starved condition.

My right hand man started his own theatre, 'socially relevant drama' dealing with abuse, mental incompetence and victims of circumstance and poverty.

I returned to a disgruntled acting career. I had sipped absinthe with the theatre gods, and now back to draft beer?

That fall at the Festival of Festivals, I received tickets for five films in which I appeared. I saw the first, and although it starred Richard Burton in one of his final roles, it was so abysmal I returned to the street without watching the others or hanging out at the reception with the beautiful people. I walked home thinking things over.

Unlike Pierre, I did not have the state of the entire country to consider, I only had the rest of my life.

I thought of Walter, our leader, the ferret, the boxer - that summer the theatre had lived.

They, the players in life’s production, had all made decisions for themselves, I suppose, and had moved on.

What was wrong with me?

- and so ended my theatre and film career.

' THE RULER INCIDENT

It had been somewhat a usual day for me as far as school was concerned. As usual I had distinguished myself by being asked to leave the room, then stand out in the hall during English class, sometime between Macbeth's tragic error of murdering the king and his wife's sleep walking scene. Being sent out in the hail didn't bother me too much; in fact it was rather pleasant. One could sneak around to the door of the class room which was open and put on a soft-shoe routine for the benefit of the class without being seen by the teacher. Eventually, the sniggers would be a bit much for him and he would either nail somebody for laughing and give him 'what for' or charge out into the hall. By that time I would be several paces down the hallway, innocently picking my nose or cleaning my fingernails. The worst part about this is that one was generally supposed to report to the principal, and he was a bit of a toughie.

Like the time the old bugger had his fly open while he was teaching a class and caught me laughing at him.

"What are you laughing at?" he'd said.

"Nothing . . .” and this would go on for a while until finally in a burst of dramatic rage and fury he'd say 'Well, well," with his sadistic smile, (he'd never got over the fact that although he had never seen action he had been a sergeant in the army); "All quiet on the western front, huh? Here's a guy who laughs at nothing. How would you like to write a thousand lines after school saying: I laugh at nothing?"

Primitive, but it was his idea of discipline.

In the afternoon we had our Student’s Union meeting, with him glowering in the background, countermanding everything he didn't agree with. This meeting was quite a laugh too, but at least it was a break from the school work and we could all sit together with two people in one desk because all of the students were in one room and there was a seating shortage. Various earth-shattering events were considered such as the high school dance, the annual picnic etc.

The action really didn't start until I'd returned to my desk. I had been sitting way on the ether side of the room getting an enormous kick out of the school apple shiners making asses of themselves up there at the front and doing my best to undermine them whenever possible. This consisted of cracking jokes and creating a general uproar in my vicinity, without the old bean realizing who it was of course. Then I would throw them off the track by jumping up and very eloquently disagreeing with and tearing apart various proposals with all the aplomb of Louis Nizer in some of his more dramatic cases. That way the teachers never realized that in the meantime I was doing my anarchist's best to foment disorder in the room. In fact some of the more intelligent ones were even proud of my oratorical skills and I could notice them having their own private little laugh about it.

When I returned to my desk and started putting everything back in order I espied my ruler. My discerning eye immediately noticed that it had been tampered with. It took no private eye to see that. Very obviously someone had taken a sharp object, a jack-knife no doubt, and dismembered the steel edge. Then after my name which I had scratched on it he had added: IS A BIG FAT SLOB.

Ach, that stung. Somebody was really in bad trouble, no doubt about that. They were really asking for it, and they were sure going to get it.

Immediately I thought back as to who had been sitting at my desk. It was the sort of thing that one casually noticed after everyone was seated just in ease your books were messed up or someone stole your pencil or your fountain pen or spilled a bottle of ink inside your desk, just for a little surprise.

It did not take me long to figure out that Jimbo had been sitting there with Creepsviile M.A. I immediately counted the creep out. He just didn't have the guts to do even something sneaky like that behind your back. It must be Jimbo, my one time best friend and still my good buddy - oh, that smarts.

But he was also my arch enemy and my rival in just about everything from girls to guitar playing. I didn't like his crude approach toward girls among other things but we still got along very well and he had come out to the farm with me and spent week-ends fishing and shooting gophers and the like. Recently though, he'd been hanging out with the town guys.

We had had a lot of good times together, we did, but now it seemed as though he wanted to bring the rift out into the open. Who did he think he was? I had treated him well. I knew he'd not been so lucky as some of us; a couple of years ago he'd seen his kid brother shot between the eyes by another kid and his home life was shaky, to put it mildly. His father visited him once or twice a year after roaming around the country the rest of the time. But now he was trying to get tough with me, especially after I'd treated him so fairly.

I'd cleaned him good once before out on the baseball diamond; that time much to everyone's delight. I don't suppose he ever forgave me for it. Rumor had it that he'd been taking boxing lessons or something and he had let it be known that he was going to get me. Maybe this was the big pitch. I had to smile to myself but I was damn mad and the old adrenaline jumping around there inside of me was making my hands shake.

I concentrated hard for the next hour on reading my western penny-awful instead of studying, surreptitiously keeping it between the covers of a larger history text. Christ, the way the old bitch butchered Macbeth it was no wonder everyone hated Literature class. I’d read it two years ago on my own and gotten more out of it.

I was concentrating so hard on Max Brand's hero my anger and venom was increasing in great proportions, though for now it was directed at that dirty, double-crossing Blacky, and not Jimbo.

I didn't even hear the teacher behind me, until all of a sadden there was a terrific whack of a yard stick breaking across my shoulder, and a short, dumpy, hysterical figure, shipped in straight from the sticks because of the teacher shortage, screaming in the most terrifying, awe-inspiring fashion imaginable. Visions of the witch's scene whisked through my head and then I thought, "Oh, my God, what have I done? It's going to have a heart attack."

I watched it subside for awhile and then she diverted her fury on my unfortunate western. She ran up to the head of the class waving it like a flag sergeant and then with great uninhibited abandon deposited it in the waste paper basket.

I was very conscious of the derision on all sides of me, with my favourite girlfriend laughing herself sick, and the rest of them, even Jimbo on the far side of the room, all killing themselves.

My fury mounted with the humiliation and I was sentenced to remain inside during the next recess when a suitable punishment would be decided on for me. How thoughtful of her.

However, by next period she was gone and there was a different teacher in our room when recess rolled around. It was worth trying to sneak out in case she hadn't tipped off the replacement. After all, one could always claim they forgot.

Fortunately it worked., but not wishing to press my luck I planned to return before bell-time in ease the old harridan checked, right after I settled a few matters, as a matter of fact.

Taking the least conspicuous way out I hustled out through the back hall. I came upon my enemy at the school gate entertaining the girls with his filthy stories. Hurriedly I confronted him with the evidence:

"Did you do this?"

"Maybe . . .”

"Never mind maybe, did you or didn't you?"

"Maybe . . . what's it to you?"

"It's a lot to me, if you maybe did it you're going to get it just as hard as if you did so you just as well own up."

"Maybe . . . " with a smirk on his face yet. I was getting mad as hell now.

"You want to make something out of it?"

This was a bit too much.

"Down by the post-office after school."

"O. K."

"Be there, you're going to get your big nose pushed in," I said in finality, rushing back to my seat before she missed me. I made it.

By home time the word had spread; the rumble was on. There was a half-hour to an hour wait before the school van came in from the other school up the road and took us back to our milk cows. This was the time in which the herculean contest would take place.

As I walked down the school steps I was suddenly very aware that I was quite alone. I had no coat or jacket and no books and the other kids were giving me strange looks. I felt like an actor about to walk on stage, swallowing quickly and pushing himself out there, fighting down the last minute panic.

Then I looked up and Jimbo was coming down the steps surrounded by about twenty comrades. It was very strange, I thought, the way people tolerate you and are even friendly with you but if they ever have to take sides, there they are; on the other side.

I gave a cynical grunt and wondered how many guys I would end up fighting with. However, by the time they reached me I was joined by my three friends. They were all country boys and they didn't care too much for the city kids anyway. They were the type that would stick by you in just such an emergency. They were all tougher than I was and it was that with one exception even I could take on any one of the town kids; and the toughest member of our group could always handle their toughest guy with ease. It made me feel kind of good walking down there with just three other fellows when there were about twenty or twenty-five in the opposing party.

By the time we were getting close to the graveled main street in front of the post office Jimbo and I had broken off and we're walking together side by side, each in front of the group we led.

When we got to the side walk just before the post-office Jimbo's second, Tom, called a halt and asked for my rings and watch; the same with Jimbo.

"That's too bad”, I thought. I had a beautiful knuckle-duster reserved for just such occasions and I had great plans for imprinting it somewhere around his eye-brow. If I could make him bleed in the eyes so he couldn't see I would have him. 0h well, no matter; if that was how they wanted it I wasn't going to object and make it too obvious.

In these last few moments the strategy was rapidly rolling around in my mind. My father, a boxer and quite a bar-room brawler in his day had cautioned us against fights. However, we should be able to take care of ourselves . . . the first punch is very important, try to make sure it's yours. Jimbo was lighter and faster than me, but I knew that if I got a good solid one in, I'd have him. I kept my father's advice in mind.

We were still on the sidewalk and usually the fight was in the street. However, I decided to catch him off guard and just as he put his books down and turned to face me, I lit one into him. It was a glancing blew off the face and the fact that he was turning must have saved him; meanwhile he recovered quickly; threw a punch and skipped out of reach.

The hit on my face didn't improve my friendly disposition and I moved in cautiously. He tried some fancy footwork; I didn't mind and calmly deflected a few blows off my arms, waiting for an opening.

“Most guys will try to hit you in the head, and they'll guard their own head, which is a natural instinct," my father had said; "But a head is a small target, first chance you get, hit him in the stomach as hard as you can."

Good advice, that was what was happening now. I led with my right, high, he moved his arm to cover and I gave him a hard punch in the gut with my left. He was winded and started to double over but I came in with a hard right to the cheek.

It was a push as much as a hit, I didn't pull the punch at all because I knew I had him on the way. Then I moved in but he was already falling over backwards. His head hit the cement with a right smart sounding smack and I smiled, momentarily flushed with victory as they say. His friends rushed over to pick him up and as he was getting up I could see tears in his eyes. Right then I lost all heart for the fight and was all for racking it in but he insisted on having another go at it.

By this time the whole darn school was down there and there was quite a commotion going on. My buddies stood by very quietly, one of them idly smoking a cigarette; none of them saying a word, like casual disinterested lookers-on. Even a lone cowboy truck driver had stopped his pick-up on the other side of the street and was looking on dispassionately. Because we were in view of the school, and fighting was a capital crime, it was decided to move behind the hall for the next segment.

We squared off and Jimbo came on strong, my killer instinct was all gone; but a careless blow on his part had ripped my shirt. There would be hell to pay when I got home and I moved in with reactivated interest. I was determined to rip his shirt right off and I rather carelessly charged in; heedless of the blows and grabbing it by the collar; I ripped it all the way down. In the background I heard Tom yelling "Lace him, lace him now." Which was precisely what he was doing. I couldn't see too well by this time. "You're fighting blind," I heard one of my friends mutter disapprovingly in the back ground. I was, and I snapped up quickly.

In his next furious onslaught I very coolly got through a good right-hander on his nose; it snapped his head back and he started to bleed profusely.

Rather than charge in for the kill; I stood back, and for a minute I thought one or two of his friends were going to come after me but one or two looks from my disapproving friends standing idly by quickly quelled their ambitions.

We walked back together after I had borrowed a jacket from one of my friends and I broached the subject of what were we going to do if the principal had seen us; after all he could have hardly missed it.

"We'll admit we were fighting and he'll kick us both out; serve us both right." Well, maybe it didn't bother him. I had no desire to get kicked out but the worst part would be facing up to it at home. No sir, not me.

The principal was standing on the steps in all his resplendent glory as we approached the school. It would appear that we were in for it.

“I want to see you two guys," he brusquely informed us. "Inside.”

We went in and sat down. He marched up and down for a while as though he was reviewing a regiment, then very dramatically informed. us, "You know what the rules are concerning fighting in this school, don't you? Pack up your books."

"But we weren't fighting," Jimbo quickly explained, "We were just horsing around."

"Yes, yes," I agreed, "we were just fooling."

"You were, were you?" as he calmly took in our bruised faces and knuckles.

He turned around, hands clasped his back, rocked on his heels, then turned dramatically.

He grunted and said "See that it doesn't happen again."

With a sigh of relief we left, just in time to get the van home.

On the way back home, things were a bit quieter than usual. Jimbo and I sat together, in silence this time. Normally he was a great card and kept the van rocking with screams and laughter all the way home. This trip he was quiet and detached as though in deep thought, strangely remote. Finally, someone said "Hey Jimbo, what's the matter; what are you so quiet about?"

"I'm going to die today," he answered simply, deadpan.

All his efforts at producing the greatest hilarity possible could net equal the results he got from this one. Screams and hysteria. All laughter resounded and everyone obviously thought that this must have been the funniest remark he’d ever made. However, his composure didn't change.

As we both got off at the same stop and went our separate ways my parting quip was "Well, remember, if you're going to die, come around and say good-by to us."

"Good-by," he answered, still serious. Some act.

This being Friday, the next day I was busy hustling around the farm. Sometime in the afternoon an old buckboard came pulling up, which was rather strange, because in the busy season one didn't go around paying social calls. Something must be wrong.

As it pulled into the yard I recognized Nick, Jimbo's uncle. He looked at me and then related; "No more Jimbo," in his thick accent. I couldn't believe it.

"Dead this morning."

Apparently he had been complaining about a head ache when he came home from school and had lain down for a while. Asked about the bruise on his head he said that he'd felt lightheaded and fell down while climbing over the fence. By the time his relatives had realized it was serious and by the time the doctor arrived he had died.

Delayed concussion of the brain.

I thought about this for a long time. That evening when our family went to pay our respects to the dead and the living I tried to beg off but they insisted I go. Everyone knew that Jimbo and I were good friends from way back and I must admit that Jimbo certainly looked good, all dressed up in a suit yet, with white silk ribbon holding his feet together. Somehow though, I lost all of my taste for fighting from that time on.

END . END . END . END . END . END . END . END . END .

It had been somewhat a usual day for me as far as school was concerned. As usual I had distinguished myself by being asked to leave the room, then stand out in the hall during English class, sometime between Macbeth's tragic error of murdering the king and his wife's sleep walking scene. Being sent out in the hail didn't bother me too much; in fact it was rather pleasant. One could sneak around to the door of the class room which was open and put on a soft-shoe routine for the benefit of the class without being seen by the teacher. Eventually, the sniggers would be a bit much for him and he would either nail somebody for laughing and give him 'what for' or charge out into the hall. By that time I would be several paces down the hallway, innocently picking my nose or cleaning my fingernails. The worst part about this is that one was generally supposed to report to the principal, and he was a bit of a toughie.

Like the time the old bugger had his fly open while he was teaching a class and caught me laughing at him.

"What are you laughing at?" he'd said.

"Nothing . . .” and this would go on for a while until finally in a burst of dramatic rage and fury he'd say 'Well, well," with his sadistic smile, (he'd never got over the fact that although he had never seen action he had been a sergeant in the army); "All quiet on the western front, huh? Here's a guy who laughs at nothing. How would you like to write a thousand lines after school saying: I laugh at nothing?"

Primitive, but it was his idea of discipline.

In the afternoon we had our Student’s Union meeting, with him glowering in the background, countermanding everything he didn't agree with. This meeting was quite a laugh too, but at least it was a break from the school work and we could all sit together with two people in one desk because all of the students were in one room and there was a seating shortage. Various earth-shattering events were considered such as the high school dance, the annual picnic etc.

The action really didn't start until I'd returned to my desk. I had been sitting way on the ether side of the room getting an enormous kick out of the school apple shiners making asses of themselves up there at the front and doing my best to undermine them whenever possible. This consisted of cracking jokes and creating a general uproar in my vicinity, without the old bean realizing who it was of course. Then I would throw them off the track by jumping up and very eloquently disagreeing with and tearing apart various proposals with all the aplomb of Louis Nizer in some of his more dramatic cases. That way the teachers never realized that in the meantime I was doing my anarchist's best to foment disorder in the room. In fact some of the more intelligent ones were even proud of my oratorical skills and I could notice them having their own private little laugh about it.

When I returned to my desk and started putting everything back in order I espied my ruler. My discerning eye immediately noticed that it had been tampered with. It took no private eye to see that. Very obviously someone had taken a sharp object, a jack-knife no doubt, and dismembered the steel edge. Then after my name which I had scratched on it he had added: IS A BIG FAT SLOB.

Ach, that stung. Somebody was really in bad trouble, no doubt about that. They were really asking for it, and they were sure going to get it.

Immediately I thought back as to who had been sitting at my desk. It was the sort of thing that one casually noticed after everyone was seated just in ease your books were messed up or someone stole your pencil or your fountain pen or spilled a bottle of ink inside your desk, just for a little surprise.

It did not take me long to figure out that Jimbo had been sitting there with Creepsviile M.A. I immediately counted the creep out. He just didn't have the guts to do even something sneaky like that behind your back. It must be Jimbo, my one time best friend and still my good buddy - oh, that smarts.

But he was also my arch enemy and my rival in just about everything from girls to guitar playing. I didn't like his crude approach toward girls among other things but we still got along very well and he had come out to the farm with me and spent week-ends fishing and shooting gophers and the like. Recently though, he'd been hanging out with the town guys.

We had had a lot of good times together, we did, but now it seemed as though he wanted to bring the rift out into the open. Who did he think he was? I had treated him well. I knew he'd not been so lucky as some of us; a couple of years ago he'd seen his kid brother shot between the eyes by another kid and his home life was shaky, to put it mildly. His father visited him once or twice a year after roaming around the country the rest of the time. But now he was trying to get tough with me, especially after I'd treated him so fairly.

I'd cleaned him good once before out on the baseball diamond; that time much to everyone's delight. I don't suppose he ever forgave me for it. Rumor had it that he'd been taking boxing lessons or something and he had let it be known that he was going to get me. Maybe this was the big pitch. I had to smile to myself but I was damn mad and the old adrenaline jumping around there inside of me was making my hands shake.

I concentrated hard for the next hour on reading my western penny-awful instead of studying, surreptitiously keeping it between the covers of a larger history text. Christ, the way the old bitch butchered Macbeth it was no wonder everyone hated Literature class. I’d read it two years ago on my own and gotten more out of it.

I was concentrating so hard on Max Brand's hero my anger and venom was increasing in great proportions, though for now it was directed at that dirty, double-crossing Blacky, and not Jimbo.

I didn't even hear the teacher behind me, until all of a sadden there was a terrific whack of a yard stick breaking across my shoulder, and a short, dumpy, hysterical figure, shipped in straight from the sticks because of the teacher shortage, screaming in the most terrifying, awe-inspiring fashion imaginable. Visions of the witch's scene whisked through my head and then I thought, "Oh, my God, what have I done? It's going to have a heart attack."

I watched it subside for awhile and then she diverted her fury on my unfortunate western. She ran up to the head of the class waving it like a flag sergeant and then with great uninhibited abandon deposited it in the waste paper basket.

I was very conscious of the derision on all sides of me, with my favourite girlfriend laughing herself sick, and the rest of them, even Jimbo on the far side of the room, all killing themselves.

My fury mounted with the humiliation and I was sentenced to remain inside during the next recess when a suitable punishment would be decided on for me. How thoughtful of her.

However, by next period she was gone and there was a different teacher in our room when recess rolled around. It was worth trying to sneak out in case she hadn't tipped off the replacement. After all, one could always claim they forgot.

Fortunately it worked., but not wishing to press my luck I planned to return before bell-time in ease the old harridan checked, right after I settled a few matters, as a matter of fact.

Taking the least conspicuous way out I hustled out through the back hall. I came upon my enemy at the school gate entertaining the girls with his filthy stories. Hurriedly I confronted him with the evidence:

"Did you do this?"

"Maybe . . .”

"Never mind maybe, did you or didn't you?"

"Maybe . . . what's it to you?"

"It's a lot to me, if you maybe did it you're going to get it just as hard as if you did so you just as well own up."

"Maybe . . . " with a smirk on his face yet. I was getting mad as hell now.

"You want to make something out of it?"

This was a bit too much.

"Down by the post-office after school."

"O. K."

"Be there, you're going to get your big nose pushed in," I said in finality, rushing back to my seat before she missed me. I made it.

By home time the word had spread; the rumble was on. There was a half-hour to an hour wait before the school van came in from the other school up the road and took us back to our milk cows. This was the time in which the herculean contest would take place.