Peter Lordly Verigin,

An Appreciation -

Larry A. Ewashen

The story unfolds . . .

White bleakness. Bitter white. All is white, unremitting, all pervading. The town, the rubble-filled alleyways [streets to some], the endless Siberian steppe that stretches forever beyond this little settlement; the air; white and frigid with snow crystals and frost, suspended. The whiteness is matched by the lingering silence, a silence that seems to pass into eternity.

Then, if one were close enough, one could see a figure, confident but cautious, making its way between the little buildings. Closer still, one could hear the silence broken by the crunch of footsteps crushing the frost hardened snow. A black figure, silhouetted, stark against the fading white, making its way through the streets as though drawn by a dim, glowing light in the distance. The figure is a man. He is young. The harsh lines of sixteen years of exile have yet to etch themselves upon his smooth, pleasant face.

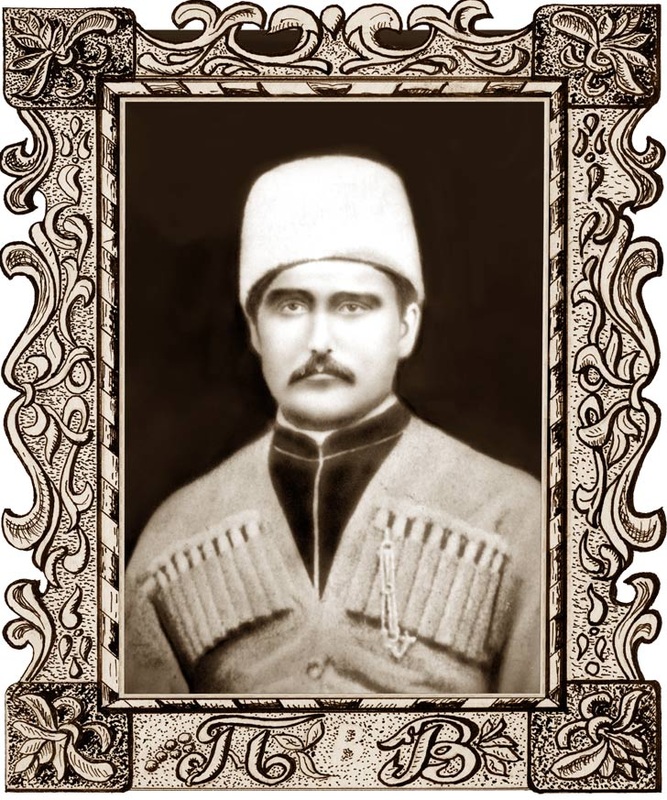

Another time, another place, years and worlds later, still guided by a light that some believed divine, this same man was to step out of a railway car in Yorkton, Saskatchewan, thousands of miles away. The year was 1902, and a newspaper reporter would write: "His manner is marked with a natural courtesy and simple dignity that would single him out anywhere. His voice is low, and of a singular sweetness. Physically, Verigin is a splendid type of his race. Tall and strongly built, and of erect and graceful carriage, he would attract attention among hundreds of good looking men. His features are regular, and his skin of an olive pallor. His hair and beard --- which is luxuriant --- are black as jet. His eyes are dark and thoughtful, and his whole expression is that of a man who has suffered much, and has triumphed over everything through the force of kingly courage and constancy."

It was true that the hardship endured during exile had merely tempered him rather than broken him. All was preparation for a future role destined to be enacted in a faraway land.Here, in the Siberian hinterland, Peter V. Verigin, this same man destined for future greatness in a land far removed from his beloved Russia, now finds himself in propitious company. As he reaches the little building with the light, he stoops to enter through the door, and is greeted by the physical warmth of the room. This warmth is accompanied by the spiritual warmth of the small group of refugees huddled inside, who cease their animated discourse momentarily, muttering low but enthusiastic words of greeting and an appeal to settle their dispute.

Then, if one were close enough, one could see a figure, confident but cautious, making its way between the little buildings. Closer still, one could hear the silence broken by the crunch of footsteps crushing the frost hardened snow. A black figure, silhouetted, stark against the fading white, making its way through the streets as though drawn by a dim, glowing light in the distance. The figure is a man. He is young. The harsh lines of sixteen years of exile have yet to etch themselves upon his smooth, pleasant face.

Another time, another place, years and worlds later, still guided by a light that some believed divine, this same man was to step out of a railway car in Yorkton, Saskatchewan, thousands of miles away. The year was 1902, and a newspaper reporter would write: "His manner is marked with a natural courtesy and simple dignity that would single him out anywhere. His voice is low, and of a singular sweetness. Physically, Verigin is a splendid type of his race. Tall and strongly built, and of erect and graceful carriage, he would attract attention among hundreds of good looking men. His features are regular, and his skin of an olive pallor. His hair and beard --- which is luxuriant --- are black as jet. His eyes are dark and thoughtful, and his whole expression is that of a man who has suffered much, and has triumphed over everything through the force of kingly courage and constancy."

It was true that the hardship endured during exile had merely tempered him rather than broken him. All was preparation for a future role destined to be enacted in a faraway land.Here, in the Siberian hinterland, Peter V. Verigin, this same man destined for future greatness in a land far removed from his beloved Russia, now finds himself in propitious company. As he reaches the little building with the light, he stoops to enter through the door, and is greeted by the physical warmth of the room. This warmth is accompanied by the spiritual warmth of the small group of refugees huddled inside, who cease their animated discourse momentarily, muttering low but enthusiastic words of greeting and an appeal to settle their dispute.

Lev Tolstoy helps . . .

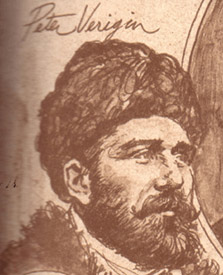

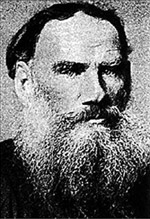

Peter's Siberian exile was not unusual. This era brought the beginnings of intellectual curiosity, the precursor of spiritual and physical emancipation - the stirring that would later result in a turbulence and a holocaust that would finally eclipse the tragic monarchy and the autocratic institution of state religion. Such exile as Verigin was experiencing was not uncommon. Many of the most intelligent and lucid thinkers, some revolutionaries, others simply outspoken humanitarians, all of whom ran against the grain of Russian royalty and the Orthodox Church; were banished to no man's land - small encampments scattered throughout the barren, frigid north and the vast, empty expanse of Siberia, hundreds and thousands of miles from populated urban centers. These radicals and political and religious outcasts formed some of the more aware and visionary individuals of Russian society of the day and included a broad spectrum of the population; princes to merchants, Counts to peasants. No one was exempt from what often was ridiculously considered heretical or unorthodox behaviour. One noble lady served many years in exile for the crime of trying to start a school for peasant children. During his exile, Peter was able to conduct a limited correspondence with such esteemed colleagues as Lev N. Tolstoy. This correspondence, based upon a mutual admiration of idealistic values, lasted from 1895 until Tolstoy's death in 1910.

Isolated from the mainstream of society, groups of these individuals were able to meet and engage in discussions concerning religion, politics, humanitarianism, and other forbidden topics. The discussions and debates would last far into the night and were an ideal forum for an exchange of contemporary thought and opinion. It was during this period of self education that Verigin formed many of his ideas and beliefs; crystallized others which he had learned and absorbed throughout his early training for leadership under the exceptional Doukhobor leader, Lukeria Vasiliyevna Kalmikova.

As a child, Verigin had demonstrated a restless moodiness that seemed to be soothed by an insatiable thirst for the revelations of 'The Living Book'; the religious tenets of the Doukhobors and the Gospels. In his life he came to literally personify the concept of Doukhobor, for the word meant 'Spirit Wrestler'. Originally, it was a derisive term given to members of this dissident group by Archbishop Ambrosius of the Russian Orthodox church in 1785, implying that they were heretics who wrestled against the spirit of the true church.

The Doukhobors accepted the name with pride, for they felt that they wrestled with the true spirit of God within them in a spiritual and nonviolent way against the spirit of mankind that was negative and evil in the struggle to more truly fulfil basic Christian beliefs in their everyday lives. In fact, the early Doukhobors had simply called themselves Christians, and many believed that Christ was the first Doukhobor.

In addition to comprehensive religious training, the young Verigin, destined to be leader, received instructions in practical management. At this time, the leader of the Doukhobors was Lukeria Kalmakova, a widow who had assumed a successful leadership after the death of her husband. Having no children of her own who might take over the leadership at the time her death, she became aware of Peter's potential and groomed him for future leadership, giving him the endearing title, ‘Lordly', meaning he belonged to the Lord because of his spiritual qualities. In 1882, at the age of 24, he moved into Lukeria's large home, and through daily instruction as her personal assistant, he soon absorbed all she had to offer in the religious aspects as well as in the daily affairs to be dealt with in the administration of a large group of communally living peasants. As a young man in her service, he had already aroused the ire of some of the most powerful elders, who were jealous of his position and who did not take kindly to his astute suggestions on 'better ways to do things.'

However, everyone knew that he was to be the new leader and he accepted the challenge selflessly, at considerable sacrifice to himself and his family. To serve the God within and his people was more important to young Verigin than to fulfil other desires or interests he might have had. When he moved into Lukeria's substantial dwelling, he had to leave behind his young wife, as well as his young son, Peter P. Verigin, a quixotic individual who would later make his own mark on Russian and Canadian history.

When Lushechka, as she was affectionately called, died four years later, the youthful Verigin was proclaimed leader after the customary six weeks of mourning. However, the actual establishment of his leadership was to be postponed for several years. The jealous rivals; the Gubonovtsi [so named after Michael Gubonov, the leader of this opposition group, who sought to control the finances of the community], brought false evidence about Peter to the authorities, and he was subsequently arrested for sedition and traitorous behaviour. No sooner had the leadership ceremonies ended in the snowy outdoors, than the police and soldiers stepped forward to arrest him. On the false charge of disloyalty to his country, and without trial, young Peter was condemned to exile for five years, a sentence that was later extended to ten years, and eventually, fifteen.

Of the fifteen years, he spent months in a dungeon in Tiflis, then in exile on the frigid Kola Peninsula and in distant Siberia; a harsh, long period of isolation which strengthened his already indomitable character and further endeared him to the hearts of the Large Party, the majority of the Doukhobors who still regarded him as leader in spite of his absence. Not until 1902 were the authorities to relent and allow him to join his brethren who had arrived in Canada in four shiploads in 1899. They were anxiously awaiting him and had been petitioning both the Russian and Canadian authorities for his release.

His exile, though causing great privation, was not totally unendurable. The worst aspect of it was the severance of ties with his family and followers. Most of the time he was not in actual prison but in internal exile. That meant that he was allowed to live more or less normally in a small village, but a village or a settlement which was months of travel away from regular contact with civilization; and which also housed the local governors and police whose responsibility was to keep an eye on all such detainees.

One's needs were provided for, and if one had some money, such an exile could be relatively comfortable. The long, dark, perpetual winter nights were illumined by their discussions and went by quicker and easier through this sharing and challenging of viewpoints of conventional society.

Peter had minimal formal education, but he could read and write and he was already well-versed in Doukhobor philosophy and thought. He made the best use of this knowledge and his abilities to become a self-educated man in the best sense of the word. During these long drawn out years he read with dedication, and corresponded by intermittent mail with some of the great intellectuals of the day, most notably, and perhaps significantly, towards the end of his sentence, the great author and humanitarian, Leo Tolstoy.

During this time, Peter confirmed the beliefs and philosophies that he had learned and formed others that would guide and shape both his own destiny and that of his followers. He instructed these followers accordingly through long letters of advice. Couriers travelled secretly for hundreds of miles by train, dog sled, and foot; a journey of many months, in order to maintain communication with their leader.

In addition to the rigors of long distance primitive travel, the messenger had to avoid the constant harassment of the police and soldiers, and occasionally adopt elaborate disguises to avoid detection. For exiles, communication with the outside world was strictly forbidden. Some of the instructions sent out at this time were to become integral concepts of Doukhobor life, most notably the admonition to refrain from the use of tobacco and alcohol out of respect for the human body as the dwelling place of God, and the further abstinence from the eating of meat out of respect for all living creatures. It was time to return to the roots of Doukhoborism. It was also at this time that the applied philosophy of pacifism became irrevocably intertwined with the fate and the destiny of the Doukhobors. The period before him under the leadership of Lukeria Kalmykova had been a prosperous and successful one for the Doukhobors. Noting that many of the community members were retaining their swords and guns along with their wealth, Verigin decided that a final, decisive act must be carried out to demonstrate once and for all the Doukhobor principle regarding the sacredness of all things living and the abhorrence of institutionalized killing sanctioned by all states in acts of war.

In the Easter spring of 1895, instructions were given; all Doukhobors must lay down their implements of warfare. Accordingly, on the first day of Easter, conscript Matvey Lebedev was the first one to lay down his weapons. He was joined by ten more Doukhobor conscripts who also laid down their rifles and stopped participating in military drill. Others in other districts followed suit.

As civilian support for these actions, a messenger brought further specific instructions. All of the weapons held by the Doukhobors must be destroyed; secretly, dramatically and simultaneously in all of the three districts of Doukhobor settlements. On the eve of St. Peter's Day, [June 29, the commemorative day of the martyred apostles, Peter and Paul, and Peter Verigin's birthday], each village gathered their swords, daggers and guns. At midnight, the weapons were doused with kerosene and lit. Assembled in a mass sobranie or meeting, the villagers sang psalms and hymns as the weapons burned.

Retribution from the Tsarist authorities was swift. Alerted by the Gubonov's of a dissident activity, the Governor sent Cossacks, armed with swords and lead-tipped whips, who rode in to quell the 'disturbance' and brutally slashed the protestors. Mass arrests, floggings, sophisticated and painful tortures followed, as well as exile into the Georgian and Tarter territories. The result of this persecution was the death of over one thousand souls out of the total exiled population of 9,000.

The position had been taken, there was to be no turning back. When Leo Tolstoy and his associate, Vladimir Chertkov, heard of the oppression of these peasants for their anti- militaristic stand, they sprang into action. An early publication in 1897 called CHRISTIAN MARTYRDOM IN RUSSIA,* followed by other appeals soon brought the attention of the world to the Doukhobor cause, and publicity and sympathy was generated throughout various countries. The Society of Friends, or the Quakers, as they were commonly known in England, protested the harsh treatment. As a result of the world wide publicity generated primarily by Tolstoy and Vladimir Chertkov, the Russian autocracy could no longer ignore these people and regard the event as a simple, internal matter - that of a group of ignorant, dissident peasants to be merely starved and beaten into submission and eventually eliminated.

Emigration for the Doukhobors having been negotiated, Tolstoy completed a novel that he had been working on and donated the proceeds of Resurrection to aid in the cost of emigration expenses. Other monies were gathered, inquiries were made, and Canada, hungering for settlers for the yet to be cultivated western prairies, welcomed the Doukhobors. The Doukhobors' requests were simple enough: they were not to be required to perform military service and they wished to farm their land communally, their land held in common in a 'bloc'.

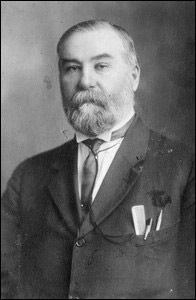

Assisting them in achieving this arrangement were Professor James Mavor, a Shavian and Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, who was active in the assistance of the immigration. Other concerned notables of the day; Tolstoy and his distinguished associates, Chertkov, Birukov and Tregubov assisted from afar, and were exiled by Russian authorities for their efforts. The well known anarchist, Prince Peter Kroptokin, a veteran of Siberian exile, had initially proposed Canada as a future homeland for the Doukhobors. Negotiations were carried on with the Canadian government, represented by Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior.

Meanwhile, in the year 1899, Peter Verigin was more alone than ever. Formerly isolated from his brethren, at least they were all in the same country, and able to maintain occasional communication. Now, his faithful followers were thousands of miles across the ocean, facing the rigors of pioneer settlement in a strange land on the inhospitable, western prairie with winter coming.

One old-timer who remembered the settlement, recalled: "When the wagon that brought us from Yorkton stopped along the river bank our family climbed off with our few packs of possessions, and we thanked the friendly farmer who helped us. After his wagon moved slowly away, our family just stood there thinking, looking and wondering. We all must have been looking at the wilderness wondering where to start. The first day we didn't even have any tools to begin with."

Another pioneer remembers: "We began to build our homes. The huts we built were dug into slopes of earth. They were sort of sod houses. We then began making ovens and baking bread. We lived like that for three years, then started to build dwellings of brick and wood. Then there was snow . . . and how the wind howled! The snow was so deep. I remember carving out tunnels to get to our neighbours."

Despite the primitive beginnings, privation and hardship, by the time Peter arrived in Canada to join his people, impressive progress had been made. When the tall, broad shouldered man with a dignified face that contained eyes of steely resolve arrived in 1902, he said little when questioned by reporters. After all, he had just completed a journey of several thousand miles, to take responsibility over a vast, somewhat scattered holding that he had never seen. He was shrewd enough not to make comments or evaluations without first observing the situation first hand and assessing what he was dealing with and what the problems were.

That there appeared to be problems, he was aware. How to deal with them, he would decide. He was aware that his duty was to the people who had been anxiously awaiting his arrival these many years. He could not propose a plan to journalists or to the Canadian government and public without first acquainting himself with the difficulties. His first purpose was to meet with his people, see the settlements and see what the needs were.

Upon his arrival, a government official reported: "He was dressed impeccably in a short blue gabardine coat, and his trousers were encased in close-fitting grey leggings, piped with black cloth; from a silken cord around his neck hung a silver watch and a gold pencil, and a large fountain pen, which was secured in his coat pocket with loops of black cloth."

A Doukhobor eyewitness account of his arrival stated: "He was met at Yorkton by his younger brother, Gregory, and by Paul Planiden, a spokesman and friend. They went first to the village of Otrodnoye where Peter's and Gregory's mother lived. It was dark and lanterns were lighted, the winter was very cold. Their mother came out on the balcony so she could greet them. Peter looked over and said: "Take mother inside or she will get a chill." The singing ended and he said: "God has taken care of us all and we are re-united. Now you are finished, disperse or you will get chilled. I invite you to come to our house tomorrow and then we can meet at greater length."

The next night, Peter talked a lot, where he had been, what his life had been like. He spoke of Jesus, how he had suffered, how he had been crucified. Then he said he wanted to visit all the villages. "Who among you can sing? I want only six people, three brothers and three sisters." He stated that he wanted to take singers with him when he visited the villages. These were chosen.

While proving himself a dynamic and skilful leader in practical matters of economic organization and farming policy, Verigin's religious training and wisdom did not lie fallow. He loved the Doukhobor choral singing, and was a talented poet and writer of psalms and prayers. Some of these, written during his exile and later, are still recited and sung today; his letters of advice and instruction possess much wisdom for the course of living a true, Christian life.

Isolated from the mainstream of society, groups of these individuals were able to meet and engage in discussions concerning religion, politics, humanitarianism, and other forbidden topics. The discussions and debates would last far into the night and were an ideal forum for an exchange of contemporary thought and opinion. It was during this period of self education that Verigin formed many of his ideas and beliefs; crystallized others which he had learned and absorbed throughout his early training for leadership under the exceptional Doukhobor leader, Lukeria Vasiliyevna Kalmikova.

As a child, Verigin had demonstrated a restless moodiness that seemed to be soothed by an insatiable thirst for the revelations of 'The Living Book'; the religious tenets of the Doukhobors and the Gospels. In his life he came to literally personify the concept of Doukhobor, for the word meant 'Spirit Wrestler'. Originally, it was a derisive term given to members of this dissident group by Archbishop Ambrosius of the Russian Orthodox church in 1785, implying that they were heretics who wrestled against the spirit of the true church.

The Doukhobors accepted the name with pride, for they felt that they wrestled with the true spirit of God within them in a spiritual and nonviolent way against the spirit of mankind that was negative and evil in the struggle to more truly fulfil basic Christian beliefs in their everyday lives. In fact, the early Doukhobors had simply called themselves Christians, and many believed that Christ was the first Doukhobor.

In addition to comprehensive religious training, the young Verigin, destined to be leader, received instructions in practical management. At this time, the leader of the Doukhobors was Lukeria Kalmakova, a widow who had assumed a successful leadership after the death of her husband. Having no children of her own who might take over the leadership at the time her death, she became aware of Peter's potential and groomed him for future leadership, giving him the endearing title, ‘Lordly', meaning he belonged to the Lord because of his spiritual qualities. In 1882, at the age of 24, he moved into Lukeria's large home, and through daily instruction as her personal assistant, he soon absorbed all she had to offer in the religious aspects as well as in the daily affairs to be dealt with in the administration of a large group of communally living peasants. As a young man in her service, he had already aroused the ire of some of the most powerful elders, who were jealous of his position and who did not take kindly to his astute suggestions on 'better ways to do things.'

However, everyone knew that he was to be the new leader and he accepted the challenge selflessly, at considerable sacrifice to himself and his family. To serve the God within and his people was more important to young Verigin than to fulfil other desires or interests he might have had. When he moved into Lukeria's substantial dwelling, he had to leave behind his young wife, as well as his young son, Peter P. Verigin, a quixotic individual who would later make his own mark on Russian and Canadian history.

When Lushechka, as she was affectionately called, died four years later, the youthful Verigin was proclaimed leader after the customary six weeks of mourning. However, the actual establishment of his leadership was to be postponed for several years. The jealous rivals; the Gubonovtsi [so named after Michael Gubonov, the leader of this opposition group, who sought to control the finances of the community], brought false evidence about Peter to the authorities, and he was subsequently arrested for sedition and traitorous behaviour. No sooner had the leadership ceremonies ended in the snowy outdoors, than the police and soldiers stepped forward to arrest him. On the false charge of disloyalty to his country, and without trial, young Peter was condemned to exile for five years, a sentence that was later extended to ten years, and eventually, fifteen.

Of the fifteen years, he spent months in a dungeon in Tiflis, then in exile on the frigid Kola Peninsula and in distant Siberia; a harsh, long period of isolation which strengthened his already indomitable character and further endeared him to the hearts of the Large Party, the majority of the Doukhobors who still regarded him as leader in spite of his absence. Not until 1902 were the authorities to relent and allow him to join his brethren who had arrived in Canada in four shiploads in 1899. They were anxiously awaiting him and had been petitioning both the Russian and Canadian authorities for his release.

His exile, though causing great privation, was not totally unendurable. The worst aspect of it was the severance of ties with his family and followers. Most of the time he was not in actual prison but in internal exile. That meant that he was allowed to live more or less normally in a small village, but a village or a settlement which was months of travel away from regular contact with civilization; and which also housed the local governors and police whose responsibility was to keep an eye on all such detainees.

One's needs were provided for, and if one had some money, such an exile could be relatively comfortable. The long, dark, perpetual winter nights were illumined by their discussions and went by quicker and easier through this sharing and challenging of viewpoints of conventional society.

Peter had minimal formal education, but he could read and write and he was already well-versed in Doukhobor philosophy and thought. He made the best use of this knowledge and his abilities to become a self-educated man in the best sense of the word. During these long drawn out years he read with dedication, and corresponded by intermittent mail with some of the great intellectuals of the day, most notably, and perhaps significantly, towards the end of his sentence, the great author and humanitarian, Leo Tolstoy.

During this time, Peter confirmed the beliefs and philosophies that he had learned and formed others that would guide and shape both his own destiny and that of his followers. He instructed these followers accordingly through long letters of advice. Couriers travelled secretly for hundreds of miles by train, dog sled, and foot; a journey of many months, in order to maintain communication with their leader.

In addition to the rigors of long distance primitive travel, the messenger had to avoid the constant harassment of the police and soldiers, and occasionally adopt elaborate disguises to avoid detection. For exiles, communication with the outside world was strictly forbidden. Some of the instructions sent out at this time were to become integral concepts of Doukhobor life, most notably the admonition to refrain from the use of tobacco and alcohol out of respect for the human body as the dwelling place of God, and the further abstinence from the eating of meat out of respect for all living creatures. It was time to return to the roots of Doukhoborism. It was also at this time that the applied philosophy of pacifism became irrevocably intertwined with the fate and the destiny of the Doukhobors. The period before him under the leadership of Lukeria Kalmykova had been a prosperous and successful one for the Doukhobors. Noting that many of the community members were retaining their swords and guns along with their wealth, Verigin decided that a final, decisive act must be carried out to demonstrate once and for all the Doukhobor principle regarding the sacredness of all things living and the abhorrence of institutionalized killing sanctioned by all states in acts of war.

In the Easter spring of 1895, instructions were given; all Doukhobors must lay down their implements of warfare. Accordingly, on the first day of Easter, conscript Matvey Lebedev was the first one to lay down his weapons. He was joined by ten more Doukhobor conscripts who also laid down their rifles and stopped participating in military drill. Others in other districts followed suit.

As civilian support for these actions, a messenger brought further specific instructions. All of the weapons held by the Doukhobors must be destroyed; secretly, dramatically and simultaneously in all of the three districts of Doukhobor settlements. On the eve of St. Peter's Day, [June 29, the commemorative day of the martyred apostles, Peter and Paul, and Peter Verigin's birthday], each village gathered their swords, daggers and guns. At midnight, the weapons were doused with kerosene and lit. Assembled in a mass sobranie or meeting, the villagers sang psalms and hymns as the weapons burned.

Retribution from the Tsarist authorities was swift. Alerted by the Gubonov's of a dissident activity, the Governor sent Cossacks, armed with swords and lead-tipped whips, who rode in to quell the 'disturbance' and brutally slashed the protestors. Mass arrests, floggings, sophisticated and painful tortures followed, as well as exile into the Georgian and Tarter territories. The result of this persecution was the death of over one thousand souls out of the total exiled population of 9,000.

The position had been taken, there was to be no turning back. When Leo Tolstoy and his associate, Vladimir Chertkov, heard of the oppression of these peasants for their anti- militaristic stand, they sprang into action. An early publication in 1897 called CHRISTIAN MARTYRDOM IN RUSSIA,* followed by other appeals soon brought the attention of the world to the Doukhobor cause, and publicity and sympathy was generated throughout various countries. The Society of Friends, or the Quakers, as they were commonly known in England, protested the harsh treatment. As a result of the world wide publicity generated primarily by Tolstoy and Vladimir Chertkov, the Russian autocracy could no longer ignore these people and regard the event as a simple, internal matter - that of a group of ignorant, dissident peasants to be merely starved and beaten into submission and eventually eliminated.

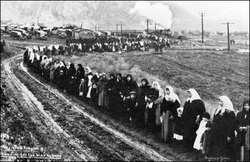

Emigration for the Doukhobors having been negotiated, Tolstoy completed a novel that he had been working on and donated the proceeds of Resurrection to aid in the cost of emigration expenses. Other monies were gathered, inquiries were made, and Canada, hungering for settlers for the yet to be cultivated western prairies, welcomed the Doukhobors. The Doukhobors' requests were simple enough: they were not to be required to perform military service and they wished to farm their land communally, their land held in common in a 'bloc'.

Assisting them in achieving this arrangement were Professor James Mavor, a Shavian and Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, who was active in the assistance of the immigration. Other concerned notables of the day; Tolstoy and his distinguished associates, Chertkov, Birukov and Tregubov assisted from afar, and were exiled by Russian authorities for their efforts. The well known anarchist, Prince Peter Kroptokin, a veteran of Siberian exile, had initially proposed Canada as a future homeland for the Doukhobors. Negotiations were carried on with the Canadian government, represented by Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior.

Meanwhile, in the year 1899, Peter Verigin was more alone than ever. Formerly isolated from his brethren, at least they were all in the same country, and able to maintain occasional communication. Now, his faithful followers were thousands of miles across the ocean, facing the rigors of pioneer settlement in a strange land on the inhospitable, western prairie with winter coming.

One old-timer who remembered the settlement, recalled: "When the wagon that brought us from Yorkton stopped along the river bank our family climbed off with our few packs of possessions, and we thanked the friendly farmer who helped us. After his wagon moved slowly away, our family just stood there thinking, looking and wondering. We all must have been looking at the wilderness wondering where to start. The first day we didn't even have any tools to begin with."

Another pioneer remembers: "We began to build our homes. The huts we built were dug into slopes of earth. They were sort of sod houses. We then began making ovens and baking bread. We lived like that for three years, then started to build dwellings of brick and wood. Then there was snow . . . and how the wind howled! The snow was so deep. I remember carving out tunnels to get to our neighbours."

Despite the primitive beginnings, privation and hardship, by the time Peter arrived in Canada to join his people, impressive progress had been made. When the tall, broad shouldered man with a dignified face that contained eyes of steely resolve arrived in 1902, he said little when questioned by reporters. After all, he had just completed a journey of several thousand miles, to take responsibility over a vast, somewhat scattered holding that he had never seen. He was shrewd enough not to make comments or evaluations without first observing the situation first hand and assessing what he was dealing with and what the problems were.

That there appeared to be problems, he was aware. How to deal with them, he would decide. He was aware that his duty was to the people who had been anxiously awaiting his arrival these many years. He could not propose a plan to journalists or to the Canadian government and public without first acquainting himself with the difficulties. His first purpose was to meet with his people, see the settlements and see what the needs were.

Upon his arrival, a government official reported: "He was dressed impeccably in a short blue gabardine coat, and his trousers were encased in close-fitting grey leggings, piped with black cloth; from a silken cord around his neck hung a silver watch and a gold pencil, and a large fountain pen, which was secured in his coat pocket with loops of black cloth."

A Doukhobor eyewitness account of his arrival stated: "He was met at Yorkton by his younger brother, Gregory, and by Paul Planiden, a spokesman and friend. They went first to the village of Otrodnoye where Peter's and Gregory's mother lived. It was dark and lanterns were lighted, the winter was very cold. Their mother came out on the balcony so she could greet them. Peter looked over and said: "Take mother inside or she will get a chill." The singing ended and he said: "God has taken care of us all and we are re-united. Now you are finished, disperse or you will get chilled. I invite you to come to our house tomorrow and then we can meet at greater length."

The next night, Peter talked a lot, where he had been, what his life had been like. He spoke of Jesus, how he had suffered, how he had been crucified. Then he said he wanted to visit all the villages. "Who among you can sing? I want only six people, three brothers and three sisters." He stated that he wanted to take singers with him when he visited the villages. These were chosen.

While proving himself a dynamic and skilful leader in practical matters of economic organization and farming policy, Verigin's religious training and wisdom did not lie fallow. He loved the Doukhobor choral singing, and was a talented poet and writer of psalms and prayers. Some of these, written during his exile and later, are still recited and sung today; his letters of advice and instruction possess much wisdom for the course of living a true, Christian life.

Adjustments . . .

To exchange the practice of communal ownership ['land in a block'] for individual title would mean an end to their lifestyle, a style and social order that was inherent to their religious and social beliefs. To swear allegiance to the British monarch, quite simply meant renouncing their pacifism, accepting registration and becoming liable for military service. They had recently endured harsh persecution in Russia, where they had forsaken friends and relatives for this cause, and left others in premature graves over this very issue. Besides, the teachings of Jesus clearly stated: "But above all things, my brethren, swear not, neither by heaven, neither by earth, neither by any other oath."

The problem facing the community was a most difficult one. To retain the benefit of the incredible effort required to transform the prairie sod into productive farmland would require foregoing the very principles that had brought the people here in the first place. Peter had reinforced the faith of the community in his abilities since rejoining his people. What he decided as to further action, most would no doubt agree to. So who is the person faced with this dilemma?

A Winnipeg news reporter at the time wrote of Verigin: "Both physically and mentally, he is perfectly equipped to be a leader of men. In height he is fully six feet, broad shouldered, deep chested, and perfectly built. He is swarthy in complexion, wears a dark moustache, and his dark hair is becoming thin. He is square faced, and his normal expression is serious but kindly... His conversation reveals a bright, keen, active mind, fully competent to deal with every problem which might arise among his people."

Peter was soon to reveal these qualities of leadership when faced with this ominous problem. Although the community would lose nearly three hundred thousand acres of improved land, surely more land could be found. Oaths of allegiance were not required for private purchase so this became an option. In due course, the option became the plan. Thus, the followers had a choice, and once more, Peter would lead the faithful to a new utopia.For the Doukhobors as a whole, this entailed another historical split. About a third of them left the community, became Independent Doukhobors, took out individual registration for the former communal land, and remained in Saskatchewan. They could not sacrifice the material achievements gained through extreme hardship and perseverance. The rest elected to follow their leader to this new place where they could pursue their beliefs and way of life without compromise. Once again, the People of the God within became pilgrims in His service.

Peter led them to a land of secluded mountain valleys, over fourteen thousand acres in the interior of British Columbia, several hundreds of miles farther west, a land 'where it took several men joining hands to reach all the way around a tree.' Such trees were a challenge to clear and to replace with gardens and orchards. Peter said that the trees were their friends, and would provide the new homes for the people.

To pay for these properties Peter raised some of the money through the dispersal sale of machinery and other goods in Saskatchewan. For the rest he negotiated a loan, with the labour of his hardworking members as collateral. From fifty to five hundred dollars an acre was paid for the land. In 1908, the trek to British Columbia began and continued until 1913, as the new communal system was set up under his dynamic leadership.

After the years of privation and suffering in exile, a lessor man might have given up when faced with this new trial. For Peter the Lordly this forced move was merely another obstacle to be overcome in the path of his search for the perfect society. Under his towering inspiration, by 1911, the Doukhobors had pushed back and cleared forests, planted over fifty thousand fruit trees, built roads, ferries, drawbridges, one of the first suspension bridges in British Columbia, sawmills, residential villages, and acquired still more land. By 1914, more than three thousand acres of land were bearing fruit, brick factories and irrigation pipe factories were built, as well as jam factories, saw mills and centres for other trades.

Peter kept track of the intimate workings of all the operations, and travelled from the headquarters in Brilliant, British Columbia to the headquarters in Verigin, Saskatchewan, where he had retained thirteen sections of farm land where grain growing and milling operations were flourishing The Saskatchewan holdings were expanded and additional land was purchased in Alberta in the Lundbreck and Cowley area. Farming and livestock raising were a feature to augment the other operations. It appeared that his dream of a self-sufficient, self-reliant, peaceful, utopian community was coming true.

He was aware, of course, of the criticism and resentment from his English-speaking neighbours. Other settlers and those with vested interests in retail business did not approve of the self-sufficiency and the mass purchasing power of the Doukhobors. While they were a boon to the general economy of the area, they provided minimal business for local merchants and their status as conscientious objectors did not endear them to the local populace during World War I. When the Great War was over, some of the Doukhobors' neighbours actually tried to seize the dearly acquired lands for the returning veterans. They also did not approve of the Doukhobors' desire to educate their children in their own schools, in the Russian language as well as English. In essence, the Doukhobors were regarded as an unusual, foreign lot, particularly when they gathered together for their sobranies dressed in their homemade clothes and chanted their mystical sounding a capella psalms and hymns.

Peter was spared the heartbreak of seeing the eventual seizure of all of the properties by the Trust and mortgage companies during the Great Depression which occurred near the end of the period of leadership of his charismatic son, Peter II, [The Cleanser]. Peter The Lordly met a tragic and premature bitterly ironic end to his own life when a bomb placed in his train coach detonated. He was assassinated near Farron, midway between Castlegar and Grand Forks.

The problem facing the community was a most difficult one. To retain the benefit of the incredible effort required to transform the prairie sod into productive farmland would require foregoing the very principles that had brought the people here in the first place. Peter had reinforced the faith of the community in his abilities since rejoining his people. What he decided as to further action, most would no doubt agree to. So who is the person faced with this dilemma?

A Winnipeg news reporter at the time wrote of Verigin: "Both physically and mentally, he is perfectly equipped to be a leader of men. In height he is fully six feet, broad shouldered, deep chested, and perfectly built. He is swarthy in complexion, wears a dark moustache, and his dark hair is becoming thin. He is square faced, and his normal expression is serious but kindly... His conversation reveals a bright, keen, active mind, fully competent to deal with every problem which might arise among his people."

Peter was soon to reveal these qualities of leadership when faced with this ominous problem. Although the community would lose nearly three hundred thousand acres of improved land, surely more land could be found. Oaths of allegiance were not required for private purchase so this became an option. In due course, the option became the plan. Thus, the followers had a choice, and once more, Peter would lead the faithful to a new utopia.For the Doukhobors as a whole, this entailed another historical split. About a third of them left the community, became Independent Doukhobors, took out individual registration for the former communal land, and remained in Saskatchewan. They could not sacrifice the material achievements gained through extreme hardship and perseverance. The rest elected to follow their leader to this new place where they could pursue their beliefs and way of life without compromise. Once again, the People of the God within became pilgrims in His service.

Peter led them to a land of secluded mountain valleys, over fourteen thousand acres in the interior of British Columbia, several hundreds of miles farther west, a land 'where it took several men joining hands to reach all the way around a tree.' Such trees were a challenge to clear and to replace with gardens and orchards. Peter said that the trees were their friends, and would provide the new homes for the people.

To pay for these properties Peter raised some of the money through the dispersal sale of machinery and other goods in Saskatchewan. For the rest he negotiated a loan, with the labour of his hardworking members as collateral. From fifty to five hundred dollars an acre was paid for the land. In 1908, the trek to British Columbia began and continued until 1913, as the new communal system was set up under his dynamic leadership.

After the years of privation and suffering in exile, a lessor man might have given up when faced with this new trial. For Peter the Lordly this forced move was merely another obstacle to be overcome in the path of his search for the perfect society. Under his towering inspiration, by 1911, the Doukhobors had pushed back and cleared forests, planted over fifty thousand fruit trees, built roads, ferries, drawbridges, one of the first suspension bridges in British Columbia, sawmills, residential villages, and acquired still more land. By 1914, more than three thousand acres of land were bearing fruit, brick factories and irrigation pipe factories were built, as well as jam factories, saw mills and centres for other trades.

Peter kept track of the intimate workings of all the operations, and travelled from the headquarters in Brilliant, British Columbia to the headquarters in Verigin, Saskatchewan, where he had retained thirteen sections of farm land where grain growing and milling operations were flourishing The Saskatchewan holdings were expanded and additional land was purchased in Alberta in the Lundbreck and Cowley area. Farming and livestock raising were a feature to augment the other operations. It appeared that his dream of a self-sufficient, self-reliant, peaceful, utopian community was coming true.

He was aware, of course, of the criticism and resentment from his English-speaking neighbours. Other settlers and those with vested interests in retail business did not approve of the self-sufficiency and the mass purchasing power of the Doukhobors. While they were a boon to the general economy of the area, they provided minimal business for local merchants and their status as conscientious objectors did not endear them to the local populace during World War I. When the Great War was over, some of the Doukhobors' neighbours actually tried to seize the dearly acquired lands for the returning veterans. They also did not approve of the Doukhobors' desire to educate their children in their own schools, in the Russian language as well as English. In essence, the Doukhobors were regarded as an unusual, foreign lot, particularly when they gathered together for their sobranies dressed in their homemade clothes and chanted their mystical sounding a capella psalms and hymns.

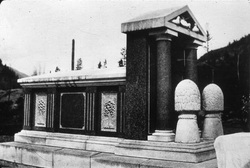

Peter was spared the heartbreak of seeing the eventual seizure of all of the properties by the Trust and mortgage companies during the Great Depression which occurred near the end of the period of leadership of his charismatic son, Peter II, [The Cleanser]. Peter The Lordly met a tragic and premature bitterly ironic end to his own life when a bomb placed in his train coach detonated. He was assassinated near Farron, midway between Castlegar and Grand Forks.

Premonitions . . .

Some time before that unkind, cruel day of October 29, 1924, he reported to his faithful housekeeper and companion, Anastasia: "They're writing me a letter. The devils have been watching me a long time, wanting to kill me. I've met and parted with everyone."Some people believe that the truly-inspired have the gift of premonition. Whether or not this particular disciple of peace and brotherhood knew of his impending death, we will never know. During the preceding year, Peter had visited all of the communities, holding meetings and giving instructions, and emphasizing the basic Doukhobor precepts of pacifism, vegetarianism and brotherly love. These exhortations even led him to California to visit the Molokans, another Russian expatriate group, and the Mennonite settlements on the prairies.

As was customary in his business dealings, he gave shrewd, perceptive instructions. But he wore the mantle of religious leader with equal zeal. He spoke to his followers as brothers, encouraging them in the Doukhobor beliefs, discussing and interpreting passages of the Gospels and The Living Book and writing prayers and psalms.

On the cool autumn evening of October 28, 1924, Peter prepared to depart on his final journey. Earlier, he had invited those nearest to him to share with him a final drink of fruit juice. Prior to his departure, he distributed nuts and raisins to the many children who were always present on his arrivals and departures. Some time later, in the early hours of October 29, near Farron, in the mountains between Castlegar and Grand Forks, his life came to an abrupt end. A tremendous explosion ripped the train coach he was riding in apart. Eight people died, one of whom was Peter Lordly Verigin. One of the most dynamic and intriguing personalities of Canadian history was swept into oblivion.

Inquiries are made, suspicious people are questioned. A strange looking gaunt man walks out of the Nelson jail. He is a free man. He has been questioned as to his communications with Peter. A crown fashioned from twenty-one oranges is on his head. He is Simon Kamenchikoff, self-proclaimed 'Czar of Heaven.' He had written Peter, warning him of his impending death. What did he know? What did he write to Peter?

"I wrote to Verigin last spring. It was a brotherly-love letter. I was in California when I had this dream. My dream was that I had left California and had gone to Saskatchewan, where all people were brothers. I felt lonely in California. In Saskatchewan my dream showed all were brothers and took wheat and put it into stooks. People were working in the fields. They suddenly heard a great noise. Mr. Verigin came and in my dream he was working some distance away from the others. He was stooping down working. I saw Peter Verigin behind me. Peter called me. I stood before him. I looked at him and saw his face was all mud. His cheeks were muddy. I said; 'Who hit you like that?' After that, Peter Verigin cried. He said: 'A strange country did that to me.'

*****

As was customary in his business dealings, he gave shrewd, perceptive instructions. But he wore the mantle of religious leader with equal zeal. He spoke to his followers as brothers, encouraging them in the Doukhobor beliefs, discussing and interpreting passages of the Gospels and The Living Book and writing prayers and psalms.

On the cool autumn evening of October 28, 1924, Peter prepared to depart on his final journey. Earlier, he had invited those nearest to him to share with him a final drink of fruit juice. Prior to his departure, he distributed nuts and raisins to the many children who were always present on his arrivals and departures. Some time later, in the early hours of October 29, near Farron, in the mountains between Castlegar and Grand Forks, his life came to an abrupt end. A tremendous explosion ripped the train coach he was riding in apart. Eight people died, one of whom was Peter Lordly Verigin. One of the most dynamic and intriguing personalities of Canadian history was swept into oblivion.

Inquiries are made, suspicious people are questioned. A strange looking gaunt man walks out of the Nelson jail. He is a free man. He has been questioned as to his communications with Peter. A crown fashioned from twenty-one oranges is on his head. He is Simon Kamenchikoff, self-proclaimed 'Czar of Heaven.' He had written Peter, warning him of his impending death. What did he know? What did he write to Peter?

"I wrote to Verigin last spring. It was a brotherly-love letter. I was in California when I had this dream. My dream was that I had left California and had gone to Saskatchewan, where all people were brothers. I felt lonely in California. In Saskatchewan my dream showed all were brothers and took wheat and put it into stooks. People were working in the fields. They suddenly heard a great noise. Mr. Verigin came and in my dream he was working some distance away from the others. He was stooping down working. I saw Peter Verigin behind me. Peter called me. I stood before him. I looked at him and saw his face was all mud. His cheeks were muddy. I said; 'Who hit you like that?' After that, Peter Verigin cried. He said: 'A strange country did that to me.'

*****

7,000 bid farewell . . .

A verse in his last devotional hymn, composed shortly before his death, is perhaps Peter V. Verigin's own finest eulogy:

Oh Lord, Thou art the light of my life,

And Thee I wish to praise forever.

From earth Thou has created me

And blessed me with a reasoning spirit.

Oh Lord, Thou art the light of my life,

And Thee I wish to praise forever.

From earth Thou has created me

And blessed me with a reasoning spirit.

Author's Note:

Peter V. Verigin died long before I was born, but his spirit was very much alive and present in our family. My grandfather was also Peter V. Verigin, a namesake. His father was Vasili Verigin, Peter's older brother, confidante and fellow exile. He was one of the regular couriers, who, along with Vasili Gregorovich Vereschagin, brought decisive instructions from Peter regarding abstinence and the Arms Burning in 1895. They were discovered, arrested, and exiled before the momentous Arms Burning in June.

I hope that my presentation of Peter is a fair one and does justice, not only to his own high ideals, but also to those many other Doukhobors who followed the thorny pathway in hopes of gaining a secure and brotherly existence for themselves and their children through their virtuous pursuit of Toil and Peaceful Life. It is to them that this book is dedicated; the legacy of their struggle is now ours.

My thanks to Peter Gritchen for providing the photographs and picture frame, Walter Golowin for the artwork in rendering the cover, and Ron Mahonin for enhancing it for publication. Certain others helped in other ways and I am grateful to them as well.

In 2008, after years of personal petitioning and lobbying, Peter V. Verigin was proclaimed ‘A Person of Historical Significance' by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Peter Lordly Verigin, An AppreciationLarry A. Ewashen

© 1988 * Revised & Edited in 2011 (All rights reserved)

I hope that my presentation of Peter is a fair one and does justice, not only to his own high ideals, but also to those many other Doukhobors who followed the thorny pathway in hopes of gaining a secure and brotherly existence for themselves and their children through their virtuous pursuit of Toil and Peaceful Life. It is to them that this book is dedicated; the legacy of their struggle is now ours.

My thanks to Peter Gritchen for providing the photographs and picture frame, Walter Golowin for the artwork in rendering the cover, and Ron Mahonin for enhancing it for publication. Certain others helped in other ways and I am grateful to them as well.

In 2008, after years of personal petitioning and lobbying, Peter V. Verigin was proclaimed ‘A Person of Historical Significance' by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Peter Lordly Verigin, An AppreciationLarry A. Ewashen

© 1988 * Revised & Edited in 2011 (All rights reserved)